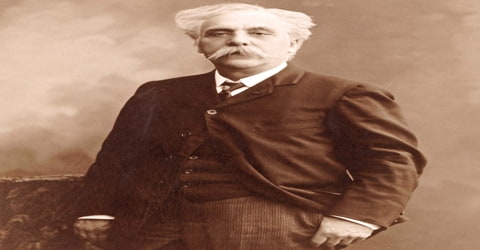

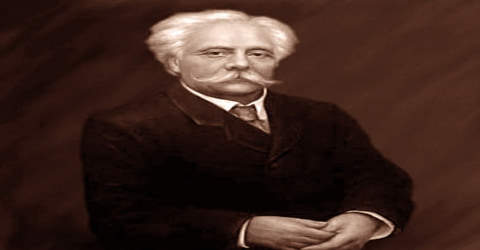

Biography of Gabriel Faure

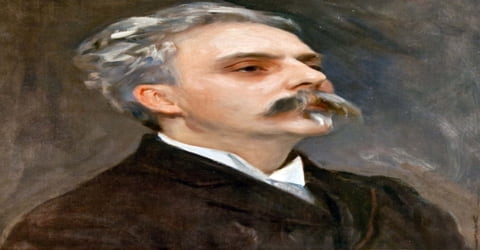

Gabriel Faure – French composer, organist, pianist, and teacher.

Name: Gabriel Urbain Fauré

Date of Birth: May 12, 1845

Place of Birth: Pamiers, France

Date of Death: November 4, 1924

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Composer, Teacher

Father: Toussaint-Honoré Fauré

Mother: Marie-Antoinette-Hélène Lalène-Laprade

Spouse/Ex: Marie Frémiet (m. 1883–1924)

Children: Emmanuel Fauré-Fremiet, Philippe Fauré-Fremiet

Early Life

Gabriel Faure, composer whose refined and gentle music influenced the course of modern French music, was born on May 12, 1845, in Pamiers, Ariège, Midi-Pyrénées, in the south of France, the fifth son and youngest of six children of Toussaint-Honoré Fauré (1810–85) and Marie-Antoinette-Hélène Lalène-Laprade (1809–87). He was one of the foremost French composers of his generation, and his musical style influenced many 20th-century composers. Among his best-known works are his Pavane, Requiem, Sicilienne, nocturnes for piano and the songs “Après un rêve” and “Clair de lune”. Although his best-known and most accessible compositions are generally his earlier ones, Fauré composed many of his most highly regarded works in his later years, in a more harmonically and melodically complex style.

Being musically inclined since early childhood, Faure turned his talent into the profession and is remembered for his-well known piece of music. The early years of Faure’s career as an organist and teacher at his alma-mater bought him meager earnings. When he became successful in his middle age, holding the important posts of organist of the Église de la Madeleine and director of the Paris Conservatoire, he still lacked time for composing; he retreated to the countryside in the summer holidays to concentrate on composition. By his last years, Fauré was recognized in France as the leading French composer of his day. An unprecedented national musical tribute was held for him in Paris in 1922, headed by the president of the French Republic. Outside France, Fauré’s music took decades to become widely accepted, except in Britain, where he had many admirers during his lifetime.

Faure struggled for almost a decade for a platform for his compositions which finally ended with his holding some influential posts such as the organist of the Église de la Madeleine and head of the Paris Conservatoire. He was acknowledged as one of the most influential musical faculties of his time. His music was characterized as sophisticated and mild and impacted the French modern music deeply.

Although Faure’s fame took time to spread across the world, he did go on to become the foremost French composer of his time in the 20th century. When he was born, Chopin was still composing, and by the time of Fauré’s death, jazz and the atonal music of the Second Viennese School were being heard. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, which describes him as the most advanced composer of his generation in France, notes that his harmonic and melodic innovations influenced the teaching of harmony for later generations. During the last twenty years of his life, he suffered from increasing deafness. In contrast with the charm of his earlier music, his works from this period are sometimes elusive and withdrawn in character, and at other times turbulent and impassioned.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Gabriel Fauré, in full Gabriel-Urbain Fauré, was born on May 12, 1845, in Pamires, Mid-Pyrenees, France to Toussaint and Marie Faure as the youngest of their six children. The composer’s paternal grandfather, Gabriel, was a butcher whose son became a schoolmaster. In 1829 Fauré’s parents married. His mother was the daughter of a minor member of the nobility. He was the only one of the six children to display musical talent; his four brothers pursued careers in journalism, politics, the army, and the civil service, and his sister had a traditional life as the wife of a public servant.

An old blind woman, who came to listen and give the boy advice, told his father of Fauré’s gift for music. In 1853 Simon-Lucien Dufaur de Saubiac, of the National Assembly, heard Fauré play and advised Toussaint-Honoré to send him to the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse (School of Classical and Religious Music, better known as the École Niedermeyer de Paris, which Louis Niedermeyer was setting up in Paris. After reflecting for a year, Fauré’s father agreed and took the nine-year-old boy to Paris in October 1854.

Fauré’s father enrolled the 9-year-old as a boarder at the École Niedermeyer in Paris, where he remained for 11 years, learning church music, organ, piano, harmony, counterpoint, and literature. In 1861, Saint-Saëns joined the school and introduced Fauré and other students to the works of more contemporary composers such as Schumann, Liszt, and Wagner.

Faure’s early music training began under the guidance of Camille Saint-Saens, who identified the talent Faure possessed and keenly spent time polishing him further. Faure’s bonding with him became strong enough to turn into a lifetime friendship. His composition ‘Cantique de Jean Racine’, Op. 11 in school was acknowledged with the first prize, premiers Prix in 1865.

Faure left the school in July 1865, as a Laureat in organ, piano, harmony, and composition, with a Maître de Chapelle diploma.

Personal Life

In July 1877, Fauré became engaged to Pauline Garcia-Viardot’s daughter Marianne Viardot, with whom he was deeply in love. To his great sorrow, she broke off the engagement in November 1877, for reasons that are not clear. This came as a big emotional setback for Faure and he eventually left Paris.

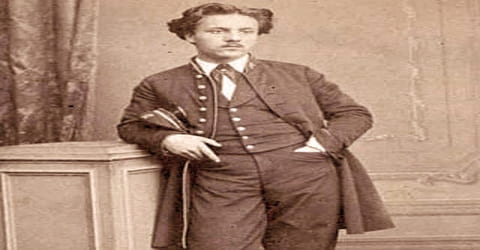

(Marie Frement and Gabriel Faure)

Faure later got married to Marie Frement (the daughter of Emmanuel Fremiet, a leading sculptor) in 1883. The marriage was affectionate, but Marie became resentful of Fauré’s frequent absences, his dislike of domestic life “horreur du domicile” and his love affairs, while she remained at home. Though Fauré valued Marie as a friend and confidante, writing to her often sometimes daily when away from home, she did not share his passionate nature, which found fulfillment elsewhere.

Fauré and his wife had two sons. The first, born in 1883, Emmanuel Fauré-Fremiet (Marie insisted on combining her family name with Fauré’s), became a biologist of international reputation. The second son, Philippe, born in 1889, became a writer; his works included histories, plays, and biographies of his father and grandfather.

About this time, or shortly afterward, Fauré’s liaison with Emma Bardac began; in Duchen’s words, “for the first time, in his late forties, he experienced a fulfilling, passionate relationship which extended over several years”. Fauré wrote the Dolly Suite for a piano duet between 1894 and 1897 and dedicated it to Bardac’s daughter Hélène, known as “Dolly”. Some people suspected that Fauré was Dolly’s father, but biographers including Nectoux and Duchen think it unlikely. Fauré’s affair with Emma Bardac is thought to have begun after Dolly was born, though there is no conclusive evidence either way.

After a romantic attachment to the singer Emma Bardac from around 1892, followed by another to the composer Adela Maddison, in 1900 Fauré met the pianist Marguerite Hasselmans, the daughter of Alphonse Hasselmans. This led to a relationship which lasted for the rest of Fauré’s life. He maintained her in a Paris apartment, and she acted openly as his companion.

Career and Works

Fauré’s musical abilities became apparent at an early age. When the Swiss composer and teacher Louis Niedermeyer heard the boy, he immediately accepted him as a pupil. Fauré studied piano with Camille Saint-Saëns, who introduced him to the music of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. While still a student, Fauré published his first composition, a work for piano, Trois romances sans paroles (1863).

Fauré’s earliest songs and piano pieces date from this period, just before his graduation in 1865, which he achieved with awards in almost every subject. For the next several years, he took on various organist positions, served for a time in the Imperial Guard, and taught. On leaving the École Niedermeyer, Fauré was appointed organist at the Church of Saint-Sauveur, at Rennes in Brittany. He took up the post in January 1866. During his four years at Rennes, he supplemented his income by taking private pupils, giving “countless piano lessons”. At Saint-Saëns’s regular prompting he continued to compose, but none of his works from this period survive. He was bored at Rennes and had an uneasy relationship with the parish priest, who correctly doubted Fauré’s religious conviction. Fauré was regularly seen stealing out during the sermon for a cigarette, and in early 1870, when he turned up to play at Mass one Sunday still in his evening clothes, having been out all night at a ball, he was asked to resign. Almost immediately, with the discreet aid of Saint-Saëns, he secured the post of assistant organist at the church of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt, in the north of Paris.

Faure served the church of Notre-Dame de Clignancourt, in the north of Paris as an assistant organist for a few months in 1870 and the rest of year was spent in serving the army in the Franco-Prussian war. He served as a music teacher in his school, Ecole Niedermeyer in Switzerland during the Paris Commune.

In 1871 Faure and his friend’s d’Indy, Lalo, Duparc, and Chabrier formed the Société Nationale de Musique, and soon after, Saint-Saëns introduced him to the salon of Pauline Viardot and Parisian musical high society. Fauré wrote his first important chamber works (the Violin Sonata No. 1 and Piano Quartet No. 1), then set out on a series of musical expeditions to meet Liszt and Wagner. He returned to Paris in October 1871 whereby he started working as a choirmaster at the Eglise Saint- Sulpice under Charles-Marie Widor, the composer, and organist.

Faure regularly visited Camille Saint- Saens and Pauline Garcia- Viardot musical salons wherein he got acquainted with some famous Parisian personalities like writers Gustave Flaubert, Ivan Turgenev and also composers like Hector Berlioz and Georges Bizet. The social meetings with the known personalities helped him set up the musical society ‘Societe Nationale Musique’ in February 1871 in order to promote the upcoming French music. Faure became its secretary in 1874.

In 1874 Fauré moved from Saint-Sulpice to the Église de la Madeleine, acting as deputy for the principal organist, Saint-Saëns, during the latter’s many absences on tour. Some admirers of Fauré’s music have expressed regret that although he played the organ professionally for four decades, he left no solo compositions for the instrument. He was renowned for his improvisations, and Saint-Saëns said of him that he was “a first class organist when he wanted to be”. Fauré preferred the piano to the organ, which he played only because it gave him a regular income. Duchen speculates that he positively disliked the organ, possibly because “for a composer of such delicacy of nuance, and such sensuality, the organ was simply not subtle enough.”

A major leap in Faure’s composition career happened with his Violin sonata’s performance at the Societe Nationale concert in January 1877. Post the retirement of Saint- Saens, Faure eventually became organist at Eglise de la Madeleine in 1877. Due to some disturbances in his life, he moved from Paris and shifted to Weimar wherein he met Franz Liszt, whose compositions Saint Saens always insisted him to play.

From 1878, Faure and Messager made trips abroad to see Wagner operas. They saw Das Rheingold and Die Walküre at the Cologne Opera; the complete Ring cycle at the Hofoper in Munich and at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London; and Die Meistersinger in Munich and at Bayreuth, where they also saw Parsifal. They frequently performed as a party piece their joint composition, the irreverent Souvenirs de Bayreuth. This short, up-tempo piano work for four hands sends up themes from The Ring. Fauré admired Wagner and had detailed knowledge of his music, but he was one of the few composers of his generation not to come under Wagner’s musical influence.

Throughout the 1880s, Faure held various positions and continued to write songs and piano pieces, but felt unsure enough of his compositional talents to attempt anything much larger than incidental music. Fauré’s pieces began to show a complexity of musical line and harmony which were to become the hallmarks of his music. He began to develop a highly original approach to tonality, in which modal harmony and altered scales figured largely. The next decade, however, is when Fauré came into his own.

The activities that Faure left unattended at ‘Societe Nationale Musique’ after leaving Paris were revived from 1883 onwards. Faure did have a tough time meeting the financial needs of his family so continued at the Eglise de la Madeleine and also gave piano and harmony lessons at times. The few compositions he managed to work on were sold to publishers at nominal rates of approx 50 francs per piece and even without royalties. His struggle continued for almost a decade with the failure to arrange a platform for his upscale compositions and so did his depression. Faure was finally appointed as the Inspector of Music Conservatories in the French provinces.

To support his family, Fauré spent most of his time running the daily services at the Madeleine and giving piano and harmony lessons. His compositions earned him a negligible amount, because his publisher bought them outright, paying him an average of 60 francs for a song, and Fauré received no royalties. During this period, he wrote several large-scale works, in addition to many piano pieces and songs, but he destroyed most of them after a few performances, only retaining a few movements in order to re-use motifs. Among the works surviving from this period is the Requiem, begun in 1887 and revised and expanded, over the years, until its final version dating from 1901. After its first performance, in 1888, the priest in charge told the composer, “We don’t need these novelties: the Madeleine’s repertoire is quite rich enough.”

Faure was named composition professor at the Paris Conservatoire in 1896. His music, although considered too advanced by most, gained recognition amongst his musical friends. This was his first truly productive phase, seeing the completion of his Requiem, the Cinq Mélodies, and the Dolly Suite, among other works. Using an economy of expression and boldness of harmony, he built the musical bridge over which his students such as Maurice Ravel and Nadia Boulanger — would cross on their journey into the 20th century.

In 1905 Fauré succeeded Théodore Dubois as director of the conservatory, and he remained in office until ill health and deafness forced him to resign in 1920. Among his students were Maurice Ravel, Georges Enesco, and Nadia Boulanger. Fauré excelled not only as a songwriter of great refinement and sensitivity but also as a composer in every branch of chamber music. He wrote more than 100 songs, including “Après un rêve” (c. 1865) and “Les Roses d’Ispahan” (1884), and song cycles that included La Bonne Chanson (1891–92) and L’Horizon chimérique (1922).

While at the Conservatoire, Faure hardly managed time for composition. His composition gained momentum only when he was off work from the Conservatoire in a laid back mood in the hotel room by the Swiss lake. Some of the famous works like the opera, Penelope; songs like La chanson d’Eve and piano pieces have come from there. The beginning of the nineteenth century marked his increasing popularity in Britain as against in Germany, Spain, and Russia where his acceptance was still slow. His trips to England gave him an opportunity to perform at the Buckingham Palace too in 1908.

Faure enriched the literature of the piano with a number of highly original and exquisitely wrought works, of which his 13 nocturnes, 13 barcaroles, and 5 impromptus are perhaps the most representative and best known. Fauré’s Ballade for piano and orchestra (1881; originally arranged for solo piano, 1877–79), two sonatas for violin and piano, and Berceuse for violin and piano (1880) are among other popular works. Élégie for cello and piano (1880; arranged for orchestra, 1896), and two sonatas for cello and piano, as well as chamber pieces, are frequently performed and recorded. From 1903 to 1921, Fauré regularly wrote music criticism for Le Figaro, a role in which he was not at ease. Nectoux writes that Fauré’s natural kindness and broad-mindedness predisposed him to emphasise the positive aspects of a work.

Fauré’s works of this period show the last, most sophisticated stages of his writing, streamlined and elegant in form. During World War I, Fauré essentially remained in Paris and had another extremely productive phase, producing, among other things, Le Jardin Clos and the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra, Op. 111, which show a force and violence that make them among the most powerful pieces in French music.

Fauré was not especially attracted to the theatre, but he wrote incidental music for several plays, including Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande (1898), as well as two lyric dramas, Prométhée (1900) and Pénélope (1913). Among his few works written for the orchestra alone is Masques et bergamasques (1919). The Messe de requiem for solo voices, chorus, orchestra, and organ (1887) did not gain immediate popularity, but it has since become one of Fauré’s most frequently performed works.

In 1920 Faure retired from the school, and the following year gave up his music critic position with Le Figaro, which he had held since 1903. Between then and his death in 1924, he would produce his great, last works: several chambers works and the song cycle L’horizon chimérique.

In 1922 the president of the republic, Alexandre Millerand, led a public tribute to Fauré, a national hommage, described in The Musical Times as “a splendid celebration at the Sorbonne, in which the most illustrious French artists participated, which brought him great joy. It was a poignant spectacle, indeed: that of a man present at a concert of his own works and able to hear not a single note. He sat gazing before him pensively, and, in spite of everything, grateful and content.”

During his school days, Faure published his first composition which was work for piano, titled Trois romances sans paroles in 1863. The very popular composition ‘Requiem’ was composed in 1888 which is believed to be inspired by his parent’s death and brings forth the emotional turmoil he went through.

Awards and Honor

On the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 Faure volunteered for military service. He took part in the action to raise the Siege of Paris and saw action at Le Bourget, Champigny, and Créteil. Faure was awarded a Croix de Guerre.

In 1920 Faure received the Grand-Croix of the Légion d’honneur, an honor rare for a musician.

Death and Legacy

Fauré,s last years were plagued by ill-health caused mainly because of his heavy smoking but it did not keep him away from the young composers who were deeply devoted to him like the Les six.

Gabriel Urbain Fauré died in Paris from pneumonia on 4 November 1924 at the age of 79. He was given a state funeral at the Église de la Madeleine and is buried in the Passy Cemetery in Paris.

Some of Faure’s exceptional orchestral works includes the orchestral suite entitled, Masues et bergamasques (based on music for a dramatic entertainment) The incidental music for the English premiere of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelleas et Melisande in 1898 and the Promethee (a lyrical tragedy composed for the amphitheatre at Beziers) were some of the well-known work of Faure during his last years.

Although Fauré had deep respect for the traditional forms of music, Fauré delighted in infusing those forms with a mélange of harmonic daring and freshness of invention. One of the most striking features of his style was his fondness for daring harmonic progressions and sudden modulations, invariably carried out with supreme elegance and a deceptive air of simplicity. His quiet and unspectacular revolution prepared the way for more sensational innovations by the modern French school.

In a centenary tribute in 1945, the musicologist Leslie Orrey wrote in The Musical Times, “‘More profound than Saint-Saëns, more varied than Lalo, more spontaneous than d’Indy, more classic than Debussy, Gabriel Fauré is the master par excellence of French music, the perfect mirror of our musical genius.’ Perhaps, when English musicians get to know his work better, these words of Roger-Ducasse will seem, not over-praise, but no more than his due.”

Information Source: