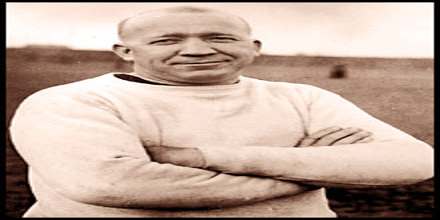

Knute Rockne – Coach, Athlete, Football Player (1888–1931)

Full name: Knute Kenneth Rockne

Date of birth: March 4, 1888

Place of birth: Voss, Norway

Date of death: March 31, 1931 (aged 43)

Place of death: Bazaar, Kansas, United States

Early Life

Knute Rockne, in full Knute Kenneth Rockne was born on March 4, 1888, Voss, Norway. He was an American gridiron football coach and Norwegian-American football player who built the University of Notre Dame in Indiana into a major power in college football and became the intercollegiate sport’s first true celebrity coach.

Rockne is regarded as one of the greatest coaches in college football history. His biography at the College Football Hall of Fame identifies him as “without question, American football’s most-renowned coach.” Rockne helped to popularize the forward pass and made the Notre Dame Fighting Irish a major factor in college football.

He ran track and played end on the University of Notre Dame football team. In 1919 he was named head coach at Notre Dame. In his 13 seasons, his “Fighting Irish” posted an impressive record (105–12–5) that included 5 undefeated seasons and 3 national championships.

Rockne learned to play football in his neighborhood and later played end in a local group called the Logan Square Tigers. He attended North West Division High School in Chicago, playing football and also running track.

After Rockne graduated from high school, he took a job as a mail dispatcher with the Post Office in Chicago for four years. When he was 22, he had saved enough money to continue his education. He headed to Notre Dame in Indiana to finish his schooling. Rockne excelled as a football end there, winning All-American honors in 1913.

After graduating he was the laboratory assistant to noted polymer chemist Julius Arthur Nieuwland at Notre Dame and helped out with the football team, but rejected further work in chemistry after receiving an offer to coach football.

The unexpected, dramatic death of Rockne startled the nation and triggered a national outpouring of grief, comparable to the deaths of presidents. President Herbert Hoover called Rockne’s death “a national loss.” King Haakon VII of Norway, Rockne’s birthplace, posthumously knighted Rockne, and sent a personal envoy to Rockne’s massive funeral. More than 100,000 people lined the route of his funeral procession, and the funeral itself was broadcast live on network radio across the United States and in Europe as well as to parts of South America and Asia.

Rockne was buried in Highland Cemetery in South Bend, which is several miles from the Notre Dame campus.

Driven by the public feeling for Rockne, the crash story played out at length in nearly all of the nation’s newspapers, and gradually evolved into a demanding public inquiry into the causes and circumstances of the crash.

The national outcry over the air disaster that killed Rockne and the seven others triggered sweeping changes to airliner design, manufacturing, operation, inspection, maintenance, regulation and crash-investigation—igniting a safety revolution that ultimately transformed airline travel worldwide, from the most dangerous form of travel to the safest form of travel.

Educational Career

Rockne attended North West Division High School in Chicago, playing football and also running track. After Rockne graduated from high school, he took a job as a mail dispatcher with the Post Office in Chicago for four years.

He was educated as a chemist at Notre Dame, and graduated in 1914 with a degree in pharmacy.

Playing and Coaching Career

Rockne learned to play football in his neighborhood and later played end in a local group called the Logan Square Tigers. He attended North West Division High School in Chicago, playing football and also running track.

On November 1, 1913, the Notre Dame squad stunned the highly regarded Army team 35–13 in a game played at West Point. Led by quarterback Charlie “Gus” Dorais and Rockne, the Notre Dame team attacked the Cadets with an offense that featured both the expected powerful running game but also long and accurate downfield forward passes from Dorais to Rockne. This game was not the “invention” of the forward pass, but it was the first major contest in which a team used the forward pass regularly throughout the game.

In 1914, he was recruited by Peggy Parratt to play for the Akron Indians. There Parratt had Rockne playing both end and halfback and teamed with him on several successful forward pass plays during their title drive. Knute wound up in Massillon, Ohio, in 1915 along with former Notre Dame teammate Dorais to play with the professional Massillon Tigers. Rockne and Dorais brought the forward pass to professional football from 1915 to 1917 when they led the Tigers to the championship in 1915. Pro Football in the Days of Rockne by Emil Klosinski maintains the worst loss ever suffered by Rockne was in 1917. He coached the “South Bend Jolly Fellows Club” when they lost 40–0 to the Toledo Maroons.

During 13 years as head coach, Rockne led his “Fighting Irish” to 105 victories, 12 losses, five ties and three national championships, including five undefeated seasons without a tie. Rockne posted the highest all-time winning percentage (.881) for a major college football coach. His schemes utilized include the eponymous Notre Dame Box offense and the 7–2–2 defense. Rockne’s box included a shift. The backfield lined up in a T-formation, then quickly shifted into a box to the left or right just as the ball was snapped.

He was very successful as an advertising pitchman, for South Bend-based Studebaker and other products. He eventually received an annual income of $75,000 from Notre Dame, which in today’s dollars is millions.

Rockne took over from his predecessor Jesse Harper in the war-torn season of 1918, posting a 3–1–2 record, losing only to the Michigan Aggies. He made his coaching debut on September 28, 1918, against Case Tech in Cleveland earning a 26–6 victory. In the backfield was Leonard Bahan, George Gipp, and Curly Lambeau. With Gipp, Rockne had an ideal handler of the forward pass.

The 1919 team had Rockne handle the line and Gus Dorais handle the backfield. The team went undefeated and was a national champion.

For all his success, Rockne also made what an Associated Press writer called “one of the greatest coaching blunders in history.” Instead of coaching his 1926 team against Carnegie Tech, Rockne traveled to Chicago for the Army–Navy Game to “write newspaper articles about it, as well as select an All-America football team.” Carnegie Tech used the coach’s absence as motivation for a 19–0 win; the upset likely cost the Irish a chance for a national title.

Rockne wrote of an attack on his coaching in the Atlanta Journal, “I am surprised that a paper of such fine, high standing as yours would allow a zipper to write in his particular vein . . . the article by Fuzzy Woodruff was not called for.”

On November 10, 1928, when the “Fighting Irish” team was losing to Army 6–0 at the end of the half, Rockne entered the locker room and told the team the words he heard on Gipp’s deathbed in 1920: “I’ve got to go, Rock. It’s all right. I’m not afraid. Some time, Rock, when the team is up against it, when things are going wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, tell them to go in there with all they’ve got and win just one for the Gipper. I don’t know where I’ll be then, Rock. But I’ll know about it, and I’ll be happy.” This inspired the team, which then outscored Army in the second half and won the game 12–6. The phrase “Win one for the Gipper” was later used as a political slogan by Ronald Reagan, who in 1940 portrayed Gipp in Knute Rockne, All American.

The 1929 and 1930 teams were also declared national champions.

Rockne was not the first coach to use the forward pass, but he helped popularize it nationally. Most football historians agree that a few schools, notably St. Louis University (under Coach Eddie Cochems), Michigan, Carlisle and Minnesota, had passing attacks in place before Rockne arrived at Notre Dame. The great majority of passing attacks, however, consisted solely of short pitches and shovel passes to stationary receivers. Additionally, few of the major Eastern teams that constituted the power center of college football at the time used the pass. In the summer of 1913, while he was a lifeguard on the beach at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, Rockne and his college teammate and roommate Gus Dorais worked on passing techniques. These were employed in games by the 1913 Notre Dame squad and subsequent Harper- and Rockne-coached teams and included many features common in modern passing, including having the passer throw the ball overhand and having the receiver run under a football and catch the ball in stride. That fall, Notre Dame upset heavily favored Army 35-13 at West Point thanks to a barrage of Dorais-to-Rockne long downfield passes.

The game played an important role in displaying the potency of the forward pass and “open offense” and convinced many coaches to add pass plays to their play books. The game is dramatized in the movies Knute Rockne, All American and The Long Gray Line.

Career history

As player:

- Notre Dame (1910–1913)

- Akron Indians (1914)

- Massillon Tigers (1915–1917)

As coach:

- Notre Dame (1914–1917) (assistant)

- South Bend J. F. C.s (1916–1917)

- Notre Dame (1918–1930)

As administrator:

- Notre Dame (1920–1930)

Personal Life

Knute Rockne was born Knut Larsen Rokne in Voss, Norway, to smith and wagonmaker Lars Knutson Rokne (1858–1912) and his wife, Martha Pedersdatter Gjermo (1859–1944). He emigrated with his parents at 5 years old to Chicago. He grew up in the Logan Square area of Chicago, on the northwest side of the city. Rockne learned to play football in his neighborhood and later played end in a local group called the Logan Square Tigers.

In 1893 Rockne moved to Chicago with his family, and in 1910 he entered Notre Dame, where he played end on the football team and was also a track star.

Rockne met Bonnie Gwendoline Skiles, an avid gardener, of Kenton, Ohio while the two were employed at Cedar Point. Bonnie (December 18, 1891 – June 2, 1956) was the daughter of George Skiles and Huldah Dry. Knute and Bonnie were married at Sts. Peter and Paul Catholic Church in Sandusky, Ohio, on July 14, 1914 with Father William F. Murphy as the officiant and Gus Dorais as the best man. They had four children: Knute Lars Jr., William Dorias, Mary Jeane and John Vincent. He converted from the Lutheran to the Roman Catholic faith on November 20, 1925. On that date, the Rev. Vincent Mooney, C.S.C., baptized Rockne in the Log Chapel on Notre Dame’s campus.

Death

Rockne died in the crash of an airplane—TWA Flight 599—in Kansas on March 31, 1931, while en route to participate in the production of the film The Spirit of Notre Dame (released October 13, 1931). He had stopped in Kansas City, to visit his two sons, Bill and Knute Jr., who were in boarding school there at the Pembroke-Country Day School. A little over an hour after taking off from Kansas City, one of the Fokker Trimotor’s wings broke up in flight. The cause of the break up was determined to be the fact that the plywood outer skin of the plane was bonded to the ribs and spars with aliphatic resin glue that was water based, and flight in rain had deteriorated the bond the point that sections of the plywood suddenly separated inflight. The plane crashed into a wheat field near Bazaar, Kansas, killing Rockne and seven others.

Coincidentally, Jess Harper, a friend of Rockne’s and the coach whom Rockne had replaced at Notre Dame, was living about 100 miles from the spot of the crash and was called to identify Rockne’s body. On the spot where the plane crashed, a memorial dedicated to the victims stands surrounded by a wire fence with wooden posts. It was maintained for many years by James Easter Heathman, who, at age 13 in 1931, was one of the first people to arrive at the site of the crash.

Honours

- Notre Dame memorializes him in the Knute Rockne Memorial Building, an athletics facility built in 1937, as well as the main football stadium.

- His name appears on streets in South Bend and in Stevensville, Michigan, (where Rockne had a summer home), and a travel plaza on the Indiana Toll Road.

- The Rockne Memorial, crash site, Bazaar, Kansas, at the site of the crash of TWA Flight 599, memorializes Rockne and the seven others who died with him. Erected by the late Easter Heathman, who as a boy was a crash eyewitness, and among the first to respond. Every five years since the crash, a memorial ceremony is held there (and at a nearby schoolhouse), drawing relatives of the victims and Rockne / Notre Dame fans from around the world. Now part of the Heathman family estate, it is accessible only by arrangement or during memorial commemorations.

- The Matfield Green rest stop travel plaza (center foyer), on the Kansas Turnpike, near Bazaar (where TWA Flight 599 crashed, killing Rockne), has a large, glassed-in exhibit commemorating Rockne (chiefly), as well as the other crash victims, and the crash.

- Allentown Central Catholic High School in Allentown, Pennsylvania, dedicated its gymnasium, Rockne Hall, to Knute Rockne.

- Taylorville, Illinois, dedicated the street next to the football field as “Knute Rockne Road.”

- The town of Rockne, Texas, was named to honor him. In 1931, the children of Sacred Heart School were given the opportunity to name their town. A vote was taken, with the children electing to name the town after Rockne, who had died in a plane crash earlier that year. On March 10, 1988, Rockne opened its post office for one day, during which a Knute Rockne 22-cent commemorative stamp was issued. A life-size bust of Rockne was unveiled on March 4, 2006.

- The Studebaker automobile company of South Bend marketed the Rockne automobile from 1931 to 1933. It was a separate product line of Studebaker and priced in the low-cost market.

- Symphonic composer Ferde Grofe composed a musical suite in Rockne’s honor shortly after the coach’s death.

- In 1940, actor Pat O’Brien portrayed Rockne in the Warner Brothers film Knute Rockne, All American, in which Rockne used the phrase “win one for the Gipper” in reference to the death bed request of George Gipp, played by Ronald Reagan.

- The short film I Am an American (1944) featured Rockne as a foreign-born citizen

- Rockne was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1951 as a charter member and in the Indiana Football Hall of Fame.

- In 1988, the United States Postal Service honored Rockne with a 22-cent commemorative postage stamp. President Ronald Reagan, who played George Gipp in the movie Knute Rockne, All American, gave an address at the Athletic & Convocation Center at the University of Notre Dame on March 9, 1988, and officially unveiled the Rockne stamp.

- In 1988, Rockne was inducted posthumously into the Scandinavian-American Hall of Fame held during Norsk Høstfest.

- A biographical musical of Rockne’s life premiered at the Theatre at the Center in Munster, Indiana, on April 3, 2008. The musical is based on a play and mini-series by Buddy Farmer.

- The U.S. Navy named a ship in the Liberty ship class after Knute Rockne in 1943. The SS Knute Rockne was scrapped in 1972.

- A statue of Rockne, as well as Ara Parseghian, both by the sculptor Armando Hinojosa of Laredo, Texas, are located on the Notre Dame campus.

- He was inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 2014.