Biography of Mary Anning

Mary Anning – English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist.

Name: Mary Anning

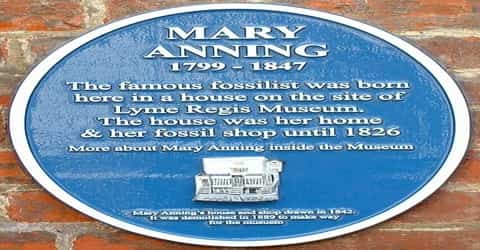

Date of Birth: 21 May 1799

Place of Birth: Lyme Regis, Dorset, Great Britain

Date of Death: 9 March 1847 (aged 47)

Place of Death: Lyme Regis, Dorset, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

Cause of death: Breast cancer

Father: Richard Anning (c. 1766–1810)

Mother: Mary Moore (c. 1764–1842)

Occupation: Fossil collector, Palaeontologist

Early Life

Mary Anning was born on 21 May 1799 in Lyme Regis in Dorset, England. She was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for important finds she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis in the county of Dorset in Southwest England. Her findings contributed to important changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth.

Mary would spend her time searching the coast looking for what she called ‘curiosities’. Later in her life, as she developed a better understanding of her finds, she realized they were actually fossils.

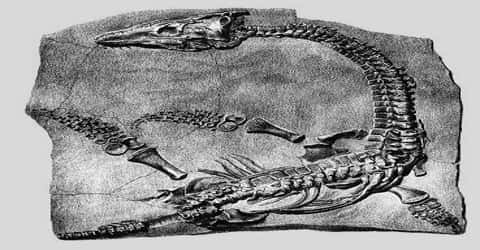

Her discoveries included the first ichthyosaur skeleton correctly identified; the first two more complete plesiosaur skeletons found; the first pterosaur skeleton located outside Germany, and important fish fossils. Her observations played a key role in the discovery that coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were fossilized feces. She also discovered that belemnite fossils contained fossilized ink sacs like those of modern cephalopods. When geologist Henry De la Beche painted Duria Antiquior, the first widely circulated pictorial representation of a scene from prehistoric life derived from fossil reconstructions, he based it largely on fossils Anning had found, and sold prints of it for her benefit.

She became well known in geological circles in Britain, Europe, and America, and was consulted on issues of anatomy as well as about collecting fossils. Nonetheless, as a woman, she was not eligible to join the Geological Society of London and she did not always receive full credit for her scientific contributions. Indeed, she wrote in a letter: “The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.” The only scientific writing of hers published in her lifetime appeared in the Magazine of Natural History in 1839, an extract from a letter that Anning had written to the magazine’s editor questioning one of its claims

Over the course of her life, she made many incredible discoveries. This made her famous among some of the most important scientists of the day. They would visit her for advice and to discuss scientific ideas about fossils. Today, Mary is remembered as one of the greatest fossil hunters to have ever lived.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Mary Anning was born on May 21, 1799, in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England to Mary Moore and Richard Anning. Her father was a carpenter who made cabinets and furniture but also collected fossils every now and then to sell for extra cash.

Richard and Molly had ten children. The first child, Mary, was born in 1794. She was followed by another girl, who died almost at once; Joseph in 1796; and another son in 1798, who died in infancy. In December that year, the oldest child, then four years old, died after her clothes caught fire, possibly while adding wood shavings to the fire. The incident was reported in the Bath Chronicle on 27 December 1798: “A child, four years of age of Mr. R. Anning, a cabinetmaker of Lyme, was left by the mother for about five minutes … in a room where there were some shavings … The girl’s clothes caught fire and she was so dreadfully burnt as to cause her death.” When another daughter was born just five months later, she was named Mary after her dead sister. More children were born after her, but none of them survived more than a couple of years. Only Mary and Joseph survived to adulthood. The high childhood mortality rate for the Anning family was not very unusual. Almost half the children born in Britain throughout the 19th century died before the age of 5, and in the crowded living conditions of early 19th century Lyme Regis, infant deaths from diseases like smallpox and measles were particularly common.

Actually, Mary almost died herself when she was just a baby! Believe it or not, on August 19th, 1800, a woman was holding Mary at a fair. Suddenly, a thunderstorm rolled in and lightning began to strike the ground. Mary, the woman holding Mary, and two other people sought shelter under an elm tree. Bad idea. One lightning bolt struck the fairgrounds and killed the woman holding Mary and the two other people. Mary miraculously escaped unharmed.

Her education was extremely limited. She was able to attend a Congregationalist Sunday school where she learned to read and write. Congregationalist doctrine, unlike that of the Church of England at the time, emphasized the importance of education for the poor. Her prized possession was a bound volume of the Dissenters’ Theological Magazine and Review, in which the family’s pastor, the Reverend James Wheaton, had published two essays, one insisting that God had created the world in six days, the other urging dissenters to study the new science of geology.

In 1810, however, she was forced to turn her hobby into a profession when her father died. It was from her father that Mary had learned to fossil hunt, and it was not long after his death that Anning made one of the most well-known discoveries in palaeontological history.

Career and Works

Mary’s family had little money so she spent most days searching the beaches with her brother looking for items to sell. When she was just 12, they discovered the skull of a mysterious creature poking out from a cliff. They thought it might be a crocodile, but what she had discovered was actually an ancient reptile called an ichthyosaur (which means ‘fish lizard’).

Mary grew up not far from the seashore. When she was little, her dad would take her to the beach. Here, Mary learned a lot of useful things from her father. At the seashore, Mary found interesting shells, fossils, and stones, which she and her family would sell to seaside vacationers. This was less of a hobby and more of a job for her, especially after her dad, the family breadwinner, unfortunately, died in 1810 by falling off of a cliff.

The family continued collecting and selling fossils together and set up a table of curiosities near the coach stop at a local inn. Although the stories about Anning tend to focus on her successes, Dennis Dean writes that her mother and brother were astute collectors too, and her parents had sold significant fossils before the father’s death.

Their first well-known find was in 1811 when Mary was 12; Joseph dug up a 4-foot ichthyosaur skull, and a few months later Mary found the rest of the skeleton. Henry Hoste Henley of Sandringham House in Sandringham, Norfolk, who was lord of the manor of Colway, near Lyme Regis, paid the family about £23 for it, and in turn, he sold it to William Bullock, a well-known collector, who displayed it in London. There it generated considerable interest, because, at a time when most people in England still believed in the Biblical account of creation, which implied that the Earth was only a few thousand years old, it raised questions about the history of living things and of the Earth itself. It was later sold for £45 and five shillings at auction in May 1819 as a “Crocodile in a Fossil State” to Charles Konig, of the British Museum, who had already suggested the name Ichthyosaurus for it.

Mary’s mother Molly initially ran the fossil business after Richard’s death, but it is unclear how much actual fossil collecting she did herself. As late as 1821, she wrote to the British Museum to request payment for a specimen. Joseph’s time was increasingly taken up by his apprenticeship to an upholsterer, but he remained active in the fossil business until at least 1825. By that time, Mary had assumed the leading role in the family business.

It was not until early 1821 that Anning made her next big discovery, with the finding of the first Plesiosaurus. The drawing Anning made was sent to the renowned George Curvier, who at first snubbed it as a fake, but eventually reversed this statement after closer examination, finally giving Anning the respect she had deserved from the scientific community.

(Drawing of the Plesiosaur that Mary Anning uncovered in 1821.)

In 1826, at the age of 27, Anning managed to save enough money to purchase a home with a glass store-front window for her shop, Anning’s Fossil Depot. The business had become important enough that the move was covered in the local paper, which noted that the shop had a fine ichthyosaur skeleton on display. Many geologists and fossil collectors from Europe and America visited Anning at Lyme, including the geologist George William Featherstonhaugh, who called Anning a “very clever funny Creature.” He purchased fossils from her for the newly opened New York Lyceum of Natural History in 1827. King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony visited her shop in 1844 and purchased an ichthyosaur skeleton for his extensive natural history collection. The king’s physician and aide, Carl Gustav Carus, wrote in his journal:

We had alighted from the carriage and were proceeding on foot when we fell in with a shop in which the most remarkable petrifications and fossil remains—the head of an Ichthyosaurus—beautiful ammonites, etc. were exhibited in the window. We entered and found the small shop and adjoining chamber completely filled with fossil productions of the coast … I found in the shop a large slab of blackish clay, in which a perfect Ichthyosaurus of at least six feet, was embedded. This specimen would have been a great acquisition for many of the cabinets of natural history on the Continent, and I consider the price demanded, £15 sterling, as very moderate.

Her discoveries did not stop st these important specimens, in 1828 Mary found the first Pterosaur to be discovered outside Germany, and the first complete remains to be discovered anywhere, naming it Pterodactylus macronyx, this did not stick for long and was later renamed by Richard Owen Dimorphodon macronyx.

These discoveries had finally ensured that anning would be remembered as an important contributor to paleontology. She was awarded an annuity by the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1883 and was the made an honorary member of the Geological Society of London, due to her being female, she was not allowed to become a regular member.

By 1830, because of difficult economic conditions in Britain that reduced the demand for fossils, coupled with long gaps between major finds, Anning was having financial problems again. Her friend the geologist Henry De la Beche assisted her by commissioning Georg Scharf to make a lithographic print based on De la Beche’s watercolor painting, Duria Antiquior, portraying life in prehistoric Dorset that was largely based on fossils Anning had found. De la Beche sold copies of the print to his fellow geologists and other wealthy friends and donated the proceeds to her. It became the first such scene from what later became known as a deep time to be widely circulated. In December 1830 she finally made another major find, a skeleton of a new type of plesiosaur, which sold for £200.

She suffered another serious financial setback in 1835 when she lost most of her life savings, about £300, in a bad investment. Sources differ somewhat on what exactly went wrong. Deborah Cadbury says that she invested with a conman who swindled her and disappeared with the money, but Shelley Emling writes that it is not clear whether the man ran off with the money or whether he died suddenly leaving Anning with no way to recover the investment. Concerned about her financial situation, her old friend William Buckland persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the British government to award her an annuity, known as a civil list pension, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology. The £25 annual pension gave her a certain amount of financial security.

Mary Anning’s life as a fossil collector and hunter began in prime time. Over many years to come, she’d go on to find many other important fossils, and many of these ended up making the news. Her finds were so impressive; she became a sort of celebrity in her day. As a result, tourists, collectors, and scientists would visit Lyme Regis to buy fossils from her.

Mary established her own business around her fossil finds. It drew plenty of tourists and scientists. She was known for having a great understanding of fossils and for being a shrewd businesswoman.

Honor

In the early 1840s, the Swiss-American naturalist, Louis Agassiz named two fossil fish species after her – Acrodus anningiae, and Belenostomus anningiae and another after her friend Elizabeth Philpot. Agassiz was grateful for the help the women had given him in examining fossil fish specimens during his visit to Lyme Regis in 1834. After her death, other species, including the ostracod Cytherelloidea anningi, and two genera, the therapsid reptile genus Anningia, and the bivalve mollusc genus Anningella, were named in her honor.

In 1999, on the 200th anniversary of her birth, an international meeting of historians, paleontologists, fossil collectors, and others interested in Anning’s life was held in Lyme Regis. In 2005 the Natural History Museum added her, alongside scientists such as Carl Linnaeus, Dorothea Bate, and William Smith, as one of the gallery characters it uses to patrol its display cases.

In 2007 American playwright/performer Claudia Stevens premiered Blue Lias, or the Fish Lizard’s Whore, a solo play with music by Allen Shearer depicting Anning in later life.

In 2012, the plesiosaur genus Anningasaura was named after her, and the species Ichthyosaurus anningae was named after her in 2015.

Death and Legacy

Mary Anning died from breast cancer at the age of 47 on 9 March 1847. Her work had tailed off during the last few years of her life because of her illness, and as some townspeople misinterpreted the effects of the increasing doses of laudanum she was taking for the pain, there had been gossip in Lyme that she had a drinking problem. She was buried on 15 March in the churchyard of St Michael’s, the local parish church. Members of the Geological Society contributed to a stained-glass window in her memory, unveiled in 1850. It depicts the six corporal acts of mercy – feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless, visiting prisoners and the sick, and the inscription reads:

“This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning of this parish, who died 9 March AD 1847 and is erected by the vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.”

In 2009 Tracy Chevalier wrote a historical novel entitled Remarkable Creatures, in which Anning and Elizabeth Philpot were the main characters, and another historical novel about Anning, Curiosity by Joan Thomas, was published in March 2010. Also that month, as part of the celebration of its 350th anniversary, the Royal Society invited a panel of experts to produce a list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science. They included Anning in the list.

Information Source: