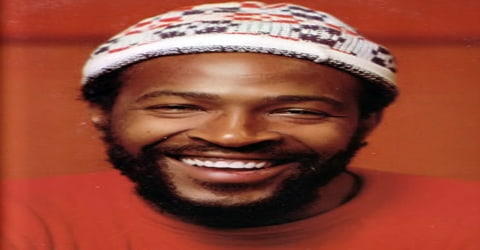

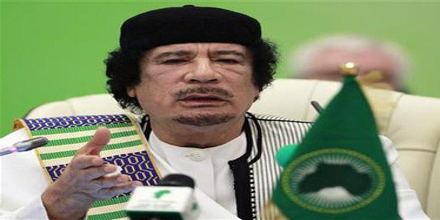

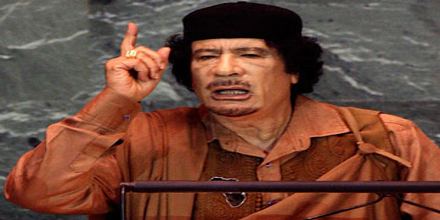

Muammar Gaddafi – Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution of Libya

Full name: Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi

Date of birth: June 7, 1942

Place of birth: Qasr Abu Hadi, Italian Libya

Date of death: 20 October 2011 (aged 68–71)

Place of death: Sirte, Libya

Cause of Death: xecution

Political party: Arab Socialist Union (1971–77), Independent (1977–2011)

Father: Abu Meniar

Mother: Aisha

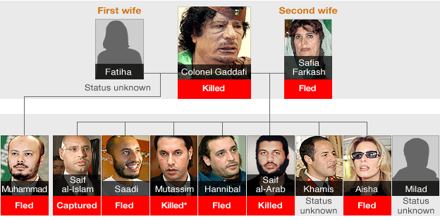

Spouse: Safia Farkash (m. 1970–2011), Fatiha al-Nuri (m. 1969–1970)

Children: Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, Ayesha Gaddafi, Moatassem-Billah Gaddafi, Al-Saadi Qadhafi, Khamis Gaddafi, Hannibal Muammar Gaddafi, Saif al-Arab al-Gaddafi, Muhammad Gaddafi

Early Life

Muammar Mohammed Abu Minyar Gaddafi was born on 7th June 1942, in Qasr Abu Hadi, Italian Libya. He was a revolutionary leader and politician who took control of the reins of the country for 42 years. In his four decades of being in power, he brought several changes in the Libyan government, first serving as the Revolutionary Chairman of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and later switching to serve as the ‘Brother Leader’ of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011. He adopted various beliefs, first as Arab nationalist to supporting Arab socialist and finally his own ideology of Third International Theory. It is interesting to note that despite of coming from a poor and underprivileged family, he showed traits of being a revolutionary since an early age. He created a revolutionary cell in the military which assisted in seizing power from King Idris in a bloodless coup. Over his years of dictatorship, he condemned international relations with western countries and broke diplomatic ties with several others thereby establishing a reputation of Libya as an ‘international pariah’. It was due to his increased dominance, his support for international terrorism and violation of human rights of Libyan citizens that led to a mass revolt which eventually resulted in the formation of National Transitional Council, the dethronement and finally the end of Gaddafi.

Gaddafi dominated Libya’s politics for four decades and was the subject of a pervasive cult of personality. A controversial and highly divisive world figure, he was decorated with various awards and lauded for both his anti-imperialist stance and his support for Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. Conversely, he was internationally condemned as a dictator and autocrat whose authoritarian administration violated the human rights of Libyan citizens and supported irredentist movements, tribal warfare, and terrorism in many other nations.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Muammar al-Gaddafi was born in a Bedouin tent in Sirte, Libya, in 1942. He was born to Abu Meniar and Aisha in an inconsequential tribal family of al-Gadhadhfa. Much of his early years were spent in Sirte, which was a desert region in Western Libya. He had three elder sisters. Born in an Italy occupied Libya, he witnessed the country gain independence in 1951. Since an early age, he was influenced by the Arab nationalist movement and had grown a fancy for Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, which later was prominent in his revolutionary tactics.

Academically, he achieved his preliminary education from a local elementary school after which the family moved to Sabha for better educational opportunities. However, his involvement in the protest against Syria’s secession from United Arab Republic led to the family relocation to Misrata.

In 1963, he enrolled at the University of Libya in Benghazi to study history but dropped out of the same to join military. He trained himself at the Royal Military Academy.

Reckoning British as imperialists and publically announcing his insurrection against everything English, he commissioned a Central Committee of the Free Officers Movement in 1964.

In April 1966, he was assigned to the United Kingdom for further training; over 9 months he underwent an English-language course at Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, an Army Air Corps signal instructors course in Bovington Camp, Dorset, and an infantry signal instructors course at Hythe, Kent. Despite later rumours to the contrary, he did not attend the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

Personal Life

He married twice in his lifetime. His first wife, Fatiha al-Nuri bore him a son in 1970 before parting ways with him the same year. Subsequently, he married Safia Farkash. The couple was blessed with seven children. He also adopted two children, Hanna Gaddafi and Milad Gaddafi.

In the 1970s and 1980s there were reports of his making sexual advances toward female reporters and members of his entourage. After the civil war, more serious charges came to light. Annick Cojean, a journalist for Le Monde, wrote in her book, Gaddafi’s Harem that Gaddafi had raped, tortured, performed urolagnia, and imprisoned hundreds or thousands of women, usually very young. Another source—Libyan psychologist Seham Sergewa—reported that several of his female bodyguards claim to have been raped by Gaddafi and senior officials. After the civil war, Luis Moreno Ocampo, prosecutor for the International Criminal Court, said there was evidence that Gaddafi told soldiers to rape women who had spoken out against his regime. In 2011 Amnesty International questioned this and other claims used to justify NATO’s war in Libya.

Political Career

After graduating, Gaddafi steadily rose through the ranks of the military. As disaffection with Idris grew, Gaddafi became involved with a movement of young officers to overthrow the king. A talented and charismatic man, Gaddafi rose to power in the group. On September 1, 1969, King Idris was overthrown while he was abroad in Turkey for medical treatment. Qaddafi was named commander in chief of the armed forces and chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council, Libya’s new ruling body. At age 27, he had become the ruler of Libya.

Gaddafi’s first order of business was to shut down the American and British military bases in Libya. He also demanded that foreign oil companies in Libya share a bigger portion of revenue with the country. Gaddafi replaced the Gregorian calendar with the Islamic one, and forbade the sale of alcohol.

Feeling threatened by a failed coup attempt by his fellow officers in December 1969, Gaddafi put in laws criminalizing political dissent. In 1970, he expelled the remaining Italians from Libya and emphasized what he saw as the battle between Arab nationalism and Western imperialism. He vocally opposed Zionism and Israel, and expelled the Jewish community from Libya. Gaddafi’s inner circle of trusted people became smaller and smaller, as power was shared by himself and a small group of associates. His intelligence agents traveled around the world to intimidate and assassinate Libyans living in exile.

Increasing state control over the oil sector, the RCC began a program of nationalization, starting with the expropriation of British Petroleum’s share of the British Petroleum-N.B. Hunt Sahir Field in December 1971. In September 1973, it was announced that all foreign oil producers active in Libya were to see 51% of their operation nationalised. For Gaddafi, this was an important step towards socialism. It proved an economic success; while gross domestic product had been $3.8 billion in 1969, it had risen to $13.7 billion in 1974, and $24.5 billion in 1979. In turn, the Libyans’ standard of life greatly improved over the first decade of Gaddafi’s administration, and by 1979 the average per-capita income was at $8,170, up from $40 in 1951; this was above the average of many industrialised countries like Italy and the U.K.

In 1973, he came up with the Third Universal Theory, which rejected the imperialism practiced by the western states and communist powers and instead advocated nationalism, leading to the creation of Islamic and Third Worlds against imperialism. He based his ideology on Islam and the teachings of the Quran.

Gaddafi’s ruling style was not just oppressive, it was eccentric. He had a cadre of female bodyguards in heels, considered himself the king of Africa, erected a tent to stay in when he traveled abroad, and dressed in strange costume-like outfits. His bizarre antics often distracted from his brutality, and earned him the nickname “the mad dog of the Middle East.”

Towards the end of the 1970s, he involved the Libyan military in several foreign conflicts, including in Egypt and Sudan, and the bloody civil war in Chad. In 1977, he dissolved the Libyan Arab Republic to form the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

In 1978, he stepped down as the Secretary General of GPC but continued his service as the Commander in Chief. The government then moved towards socialism and paid much emphasis on equality. This raised alarm for the government as many turned critical of it. The beginning of the 1980s spelled economic disaster for Libya as oil revenues dropped considerably. Worsening the economic damage was spoiled relations with other foreign countries.

In 1981, the US President Ronald Reagan called him ‘International pariah’ and ‘mad dog of the Middle East’. Reagan further reduced the involvement of US embassy workers and companies to diminish their operation in Libya to zero.

In 1986, Libyan terrorists were thought to be behind the bombing of a West Berlin dance club that killed three and injured scores of people. The U.S. in turn, under President Ronald Reagan’s administration, bombed specific targets in Libya that included Gaddafi’s residence in Tripoli.

In the most famous instance of the country’s connection to terrorism, Libya was implicated in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing. A plane carrying 259 people blew up near Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all on board, with falling debris killing 11 civilians on the ground. Libyan terrorists, including an in-law of Gaddafi’s, were also believed to be behind the destruction of a French passenger jet in 1989, killing all 170 on board.

In 1990s, the relationship between Gaddafi and the West began to thaw. As Gaddafi faced a growing threat from Islamists who opposed his rule, he began to share information with the British and American intelligence services. In 1994, Nelson Mandela persuaded the Libyan leader to hand over the suspects from the Lockerbie bombing. It wasn’t long before Gaddafi had mended relations with the West on many fronts.

Gaddafi was welcomed in Western capitals, and Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi counted him among his close friends. Gaddafi’s son and heir apparent, Seif al-Islam Gaddafi, mixed with London’s high society for several years. Many critics of the newfound friendship of Gaddafi and the West believed it was based on business and access to oil.

In 2001, the United Nations eased sanctions on Libya, and foreign oil companies worked out lucrative new contracts to operate in the country. The influx of money to Libya made Gaddafi, his family and his associates even wealthier. The disparity between the ruling family and the masses became ever more apparent.

Following the start of the Arab Spring in 2011, Gaddafi spoke out in favour of Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, then threatened by the Tunisian Revolution. He suggested that Tunisia’s people would be satisfied if Ben Ali introduced a Jamahiriyah system there. Fearing domestic protest, Libya’s government implemented preventative measures by reducing food prices, purging the army leadership of potential defectors and releasing several Islamist prisoners. They proved ineffective, and on 17 February 2011, major protests broke out against Gaddafi’s government. Unlike Tunisia or Egypt, Libya was largely religiously homogenous and had no strong Islamist movement, but there was widespread dissatisfaction with the corruption and entrenched systems of patronage, while unemployment had reached around 30%.

By the end of February 2011, the opposition had gained control over much of the country, and the rebels formed a governing body called the National Transitional Council. The opposition surrounded Tripoli, where Gaddafi still had some support. Most of the international community expressed support for the NTC and called for the ouster of Gaddafi. At the end of March, a NATO coalition began to provide support for the rebel forces in the form of airstrikes and a no-fly zone. NATO’s military intervention over the next six months proved to be decisive. In April, a NATO attack killed one of Gaddafi’s sons. When Tripoli fell to rebel forces in late August, it was seen as a major victory for the opposition and a symbolic end for Gaddafi’s rule.

In June 2011, the International Criminal Court issued warrants for the arrest of Gaddafi, his son Seif al-Islam, and his brother-in-law for crimes against humanity. In July, more than 30 countries recognized the NTC as the legitimate government of Libya. Gaddafi had lost control of Libya, but his whereabouts were still unknown.

Death and Legacy

On October 20, 2011, Libyan officials announced that Muammar al-Gaddafi had died near his hometown of Sirte, Libya. Early reports had conflicting accounts of his death, with some stating that he had been killed in a gun battle and others claiming that he had been targeted by a NATO aerial attack. Video circulated of Gaddafi’s bloodied body being dragged around by fighters.

For months, Gaddafi and his family had been at large, believed to be hiding in the western part of the country where they still had small pockets of support. As news of the former dictator’s death spread, Libyans poured into the streets, celebrating the what many hailed as the culmination of their revolution.

Post Gaddafi, Libya has continued to be embroiled in violence. With state authority eventually being held by the General National Congress, various militia groups have vied for power. Dozens of political figures and activists in Benghazi have been killed, with many having to leave the area. The country has also seen a succession of interim prime ministers.

Public Image

According to Vandewalle, Gaddafi “dominated Libya’s political life” during his period in power. A cult of personality devoted to Gaddafi existed in Libya. His face appeared on a wide variety of items, including postage stamps, watches, and school satchels. Quotations from The Green Book appeared on a wide variety of places, from street walls to airports and pens, and were put to pop music for public release. Gaddafi claimed that he disliked this personality cult, but that he tolerated it because Libya’s people adored him. He was notably confrontational in his approach to foreign powers, and generally shunned Western ambassadors and diplomats, believing them to be spies. Gaddafi was preoccupied with his own security, regularly changing where he slept and sometimes grounding all other planes in Libya when he was flying. He made very particular requests when traveling to foreign nations. During his trips to Rome, Paris, Madrid, Moscow, and New York City, he resided in a bulletproof tent, following his Bedouin traditions.

Starting in the 1980s, he travelled with his all-female Amazonian Guard, who were allegedly sworn to a life of celibacy. However, according to psychologist Seham Sergewa, after the civil war several of the guards told her they had been pressured into joining and raped by Gaddafi and senior officials. He hired several Ukrainian nurses to care for him and his family’s health, and traveled everywhere with his trusted Ukrainian nurse Halyna Kolotnytska. Kolotnytska’s daughter denied the suggestion that the relationship was anything but professional.