Introduction

Women have been oppressed for as long as history. This oppression is a very similar tragedy to the oppression that occurs daily towards all kinds of minority groups, but women are not a minority group. There are actually more women on Earth than there are men. Women are not defined by skin color, by spoken language, or by class. Since women are not a minority group, their unequal treatment has gone unnoticed by many. The birth of feminism is to establish the women equal rights as men in society.

Statement of the Problem

Feminism is an important issue in the present time, especially to the women. Here, our intention is to describe all the issue related feminism; what is it, how it is emerged, related theory etc.

Objective of the report

The objective of our report is

To clarify what is feminism

To describe how feminism has emerged

To describe different types of feminism

To describe related theory about feminism

To describe what is the condition of feminism in Bangladesh

To describe what is the thinking of our varsity girl about feminism

METHODOLOGY

2.1 Information Need

Since our topic is on feminism, we needed both primary data and secondary data.

2.2 Source of Data

For our report, we collect and use the data from one source:

2.2.1 Primary data

2.2.2 Secondary Data

2.2.1 Primary data:

We have collected primary data through the survey. For this we have used questionnaire and collected the ideas for the people about our report topic.

Survey Data:

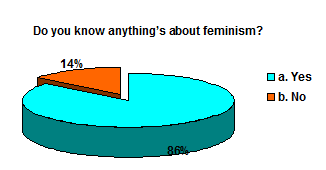

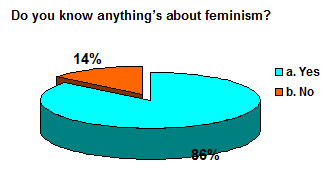

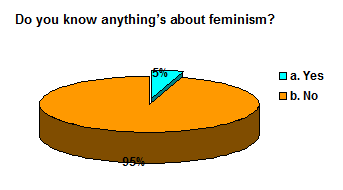

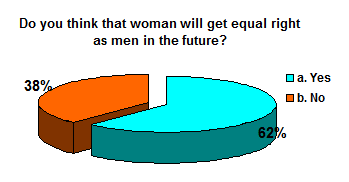

Number of people: We have surveyed 21 girls for our report.

Where I Survey: We have chosen all girls from our University.

Number of Question: In our questionnaire we have selected 8th questions.

2.2.2 Secondary Data:

We have collected secondary data form web sites.

2.3 Conceptual Framework

We have not used any kind of complicated word in our report. Anybody can simply understand the whole things, just only need careful reading. Moreover, we have not tried to oversimplify to keep a standard and we have maintained judicial attitudes.

Part- B

Feminism

What is feminism?

Feminism is a belief in the right of women to have political, social, and economic equality with men. Feminism is a diverse collection of social theories, political movements, and moral philosophies. Some versions are critical of past and present social relations. Many focus on analyzing what they believe to be social constructions of gender and sexuality. Many focus on studying gender inequality and promoting women’s rights, interests, and issues.

Feminist theory aims to understand the nature of gender inequality and focuses on gender politics, power relations and sexuality. Feminism is also based on experiences of gender roles and relations. Feminist political activism commonly campaign on issues such as reproductive rights, violence within a domestic partnership, maternity leave, equal pay, sexual harassment, discrimination, and sexual violence. Themes explored in feminism include patriarchy, stereotyping, objectification, sexual objectification, and oppression.

Chapter- 2

Feminist Principles

Feminist principles guide the work that we do within equality-seeking organizations, as well as the way that we do it. Taking the time to examine or revisit our feminist principles can assist in deepening our understanding of feminist practices and processes, and reconnecting with our feminist basis of unity.

On the following pages you will find a discussion of thirteen feminist principles, practices and processes that have been identified and informed by a diversity of women’s backgrounds and experiences in feminist organizing that can help us build active, healthy, participatory equality seeking organization. You will find a scenario exercise for each of the feminist principles, as well as a set of workshop questions. These may be used separately during shorter meetings, or together during a longer workshop. (A sample workshop on feminist principles, practices and processes is included in section three.)

These are the feminist principles of:

1. Accountability

2. Advocacy

3. Challenge and Conflict

4. Choice

5. Consultation

6. Diversity

7. Education and Mentoring

8. Equality and Inclusion

9. Evaluation

10. Joy and Celebration

11. Leadership

12. Power Sharing

13. Safety

This may be the first time you have considered these principles. You may also be very familiar with them, or have others of your own. Whether we are emerging organizations or new members of an established group, reflecting on our principles, practices and processes can assist in connecting the meaning of feminism to our equality-seeking mandate.

The following discussion of each principle begins with a working definition and a feminist quote, and concludes with a scenario exercise and a set of workshop questions. These may be helpful in sparking discussions, facilitating workshops, and talking with other women and groups about the meaning of feminism to equality-seeking work.

1.1 Accountability

The feminist principle of accountability means we hold ourselves responsible to the women we work for and with in our pursuit of equality and inclusion. We are accountable through our practice of feminist principles and our commitment to feminism as our basis of unity.

1.2 Advocacy

The feminist principle of advocacy means supporting or recommending a position or course of action that has been informed by women’s experiences in our efforts to bring about equality and inclusion. Advocacy may take place through a variety of actions and strategies, ranging from demonstrations and protests to meetings and dialogue.

1.3 Challenge and Conflict

The feminist principle of challenge and conflict means that we accept conflict as inevitable while embracing challenge as the practice of calling into account, questioning, provoking thought, and reflecting. When we are committed to respectful ways of challenging and healthy conflict resolution processes, we deepen our individual and collective understanding.

1.4 Choice

The principle of choice means that we respect, support and advocate for women’s individual and collective right to make our own decisions about our bodies, our families, our jobs and our lives. The right to choose is integral to the feminist pursuit of social, legal, political, economic and cultural equality for women.

1.5 Consultation

The feminist principle of consultation means working collaboratively, seeking guidance and sharing information to develop strategies and actions to advance women’s equality.

1.6 Diversity

The feminist principle of diversity means that we respect, accept and celebrate our individual and collective differences as women, including those based on age, race, culture, ability, sexuality, geography, religion, politics, class, education and image, among others.

1.7 Education and Mentoring

The feminist principle of education and mentoring means creating opportunities to guide, counsel, coach, tutor and teach each other. Constantly sharing our skills, knowledge, history and understanding makes our organizations healthier and more effective in our pursuit of equality and inclusion.

1.8 Equality and Inclusion

The feminist principle of equality and inclusion means, as feminist organizations, we apply a feminist analysis to policies, programs, practices, services and legislation to ensure they are inclusive of women and other marginalized groups. We advocate for equity practices to eliminate the barriers to inclusion, recognizing that inclusion leads to equality.

1.9 Evaluation

The feminist principle of evaluation means taking the time to reflect upon whether we are achieving what we set out to do as well as how we are going about it. Evaluation presents an opportunity to examine the work that we do and the feminist principles, practices and processes that guide and inform this work.

1.10 Joy and Celebration

The feminist principle of joy and celebration means that we honor each other and our work through sharing joy and celebrating our commitment to woman-centered, feminist principles, practices and processes.

1.11 Leadership

The feminist principle of leadership means embracing and sharing the skills and knowledge of individual women, and providing opportunities for all women to develop their leadership potential. As feminist organizations, we invest power and trust in our leaders with the expectation they will draw upon feminist practices and processes in our efforts toward equality and inclusion.

1.12 Power Sharing

The feminist principle of power sharing means we are committed to creating balanced power relationships through democratic practices of shared leadership, decision-making, authority, and responsibility.

1.13 Safety

The feminist principle of safety means we are committed, as women and organizations, to creating environments where all women feel comfortable and safe to participate in our work toward equality. We build safety through healthy practices of inclusion, respect, self-care and confidentiality.

Chapter- 2

History

Feminists and scholars have divided the movement’s history into three “waves”. The first wave refers mainly to women’s suffrage movements of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (mainly concerned with women’s right to vote). The second wave refers to the ideas and actions associated with the women’s liberation movement beginning in the 1960s (which campaigned for legal and social equality for women). The third wave refers to a continuation of, and a reaction to, the perceived failures of, second-wave feminism, beginning in the 1990s.

2.1 First wave

First-wave feminism refers to a period of feminist activity during the nineteenth century and early twentieth century in the United Kingdom and the United States. Originally it focused on the promotion of equal contract and property rights for women and the opposition to chattel marriage and ownership of married women (and their children) by their husbands. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, activism focused primarily on gaining political power, particularly the right of women’s suffrage. Yet, feminists such as Voltairine de Cleyre and Margaret Sanger were still active in campaigning for women’s sexual, reproductive, and economic rights at this time.

In Britain the Suffragettes campaigned for the women’s vote. In 1918 the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who owned houses. In 1928 this was extended to all women over twenty-one. In the United States leaders of this movement included Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who each campaigned for the abolition of slavery prior to championing women’s right to vote. Other important leaders include Lucy Stone, Olympia Brown, and Helen Pitts. American first-wave feminism involved a wide range of women, some belonging to conservative Christian groups (such as Frances Willard and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union), others resembling the diversity and radicalism of much of second-wave feminism (such as Matilda Joslyn Gage and the National Woman Suffrage Association). In the United States first-wave feminism is considered to have ended with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1919), granting women the right to vote in all states.The term first wave, was coined retrospectively after the term second-wave feminism began to be used to describe a newer feminist movement that focused as much on fighting social and cultural inequalities as political inequalities.

The first wave of feminists, in contrast to the second wave, was hostile to abortion.

2.2 Second wave

Second-wave feminism refers to a period of feminist activity beginning in the early 1960s and lasting through the late 1980s. The scholar Imelda Whelehan suggests that the second wave was a continuation of the earlier phase of feminism involving the suffragettes in the UK and USA. Second-wave feminism has continued to exist since that time and coexists with what is termed third-wave feminism. The scholar Estelle Freedman compares first and second-wave feminism saying that the first wave focused on rights such as suffrage, whereas the second wave was largely concerned with other issues of equality, such as ending discrimination.

The feminist activist and author Carol Hanisch coined the slogan “The Personal is Political” which became synonymous with the second wave. Second-wave feminists saw women’s cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked and encouraged women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized and as reflecting sexist power structures.

2.2.1 Women’s Liberation in the USA

The phrase “Women’s Liberation” was first used in the United States in 1964 and first appeared in print in 1966. By 1968, although the term Women’s Liberation Front appeared in the magazine Ramparts, it was starting to refer to the whole women’s movement. Bra-burning also became associated with the movement, though the actual prevalence of bra-burning is debatable. One of the most vocal critics of the women’s liberation movement has been the African American feminist and intellectual Gloria Jean Watkins (who uses the pseudonym “bell hooks”) who argues that this movement glossed over race and class and thus failed to address “the issues that divided women”. She highlighted the lack of minority voices in the women’s movement in her book Feminist theory from margin to center (1984).

2.2.2 The Feminine Mystique

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) criticized the idea that women could only find fulfillment through childrearing and homemaking. According to Friedan’s obituary in the New York Times, The Feminine Mystique “ignited the contemporary women’s movement in 1963 and as a result permanently transformed the social fabric of the United States and countries around the world” and “is widely regarded as one of the most influential nonfiction books of the 20th century.” In the book Friedan hypothesizes that women are victims of a false belief system that requires them to find identity and meaning in their lives through their husbands and children. Such a system causes women to completely lose their identity in that of their family. Friedan specifically locates this system among post-World War II middle-class suburban communities. At the same time, America’s post-war economic boom had led to the development of new technologies that were supposed to make household work less difficult, but that often had the result of making women’s work less meaningful and valuable.

2.3 Third wave

Third-wave feminism began in the early 1990s, arising as a response to perceived failures of the second wave and also as a response to the backlash against initiatives and movements created by the second wave. Third-wave feminism seeks to challenge or avoid what it deems the second wave’s essentialist definitions of femininity, which (according to them) over-emphasize the experiences of upper middle-class white women.

A post-structuralist interpretation of gender and sexuality is central to much of the third wave’s ideology. Third-wave feminists often focus on “micro-politics” and challenge the second wave’s paradigm as to what is, or is not, good for females. The third wave has its origins in the mid-1980s. Feminist leaders rooted in the second wave like Gloria Anzaldua, bell hooks, Chela Sandoval, Cherrie Moraga, Audre Lorde, Maxine Hong Kingston, and many other black feminists, sought to negotiate a space within feminist thought for consideration of race-related subjectivities.

Third-wave feminism also contains internal debates between difference feminists such as the psychologist Carol Gilligan (who believes that there are important differences between the sexes) and those who believe that there are no inherent differences between the sexes and contend that gender roles are due to social conditioning.

2.4 Post-feminism

Post-feminism describes a range of viewpoints reacting to feminism. While not being “anti-feminist”, post-feminists believe that women have achieved second wave goals while being critical of third wave feminist goals. The term was first used in the 1980s to describe a backlash against second-wave feminism. It is now a label for a wide range of theories that take critical approaches to previous feminist discourses and includes challenges to the second wave’s ideas. Other post-feminists say that feminism is no longer relevant to today’s society. Amelia Jones has written that the post-feminist texts which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s portrayed second-wave feminism as a monolithic entity and criticized it using generalizations.

One of the earliest uses of the term was in Susan Bolotin’s 1982 article “Voices of the Post-Feminist Generation,” published in New York Times Magazine. This article was based on a number of interviews with women who largely agreed with the goals of feminism, but did not identify as feminists.

Some contemporary feminists, such as Katha Pollitt or Nadine Strossen, consider feminism to hold simply that “women are people”. Views that separate the sexes rather than unite them are considered by these writers to be sexist rather than feminist.

In her book Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, Susan Faludi argues that a backlash against second wave feminism in the 1980s has successfully re-defined feminism through its terms. She argues that it constructed the women’s liberation movement as the source of many of the problems alleged to be plaguing women in the late 1980s. She also argues that many of these problems are illusory, constructed by the media without reliable evidence. According to her, this type of backlash is a historical trend, recurring when it appears that women have made substantial gains in their efforts to obtain equal rights.

Angela McRobbie argues that adding the prefix post to feminism undermines the strides that feminism has made in achieving equality for everyone, including women. Post-feminism gives the impression that equality has been achieved and that feminists can now focus on something else entirely. McRobbie believes that post-feminism is most clearly seen on so-called feminist media products, such as Bridget Jones’s Diary, Sex and the City, and Ally McBeal. Female characters like Bridget Jones and Carrie Bradshaw claim to be liberated and clearly enjoy their sexuality, but what they are constantly searching for is the one man who will make everything worthwhile.

2.5 French feminism

French feminism refers to a branch of feminist thinking from a group of feminists in France from the 1970s to the 1990s. French feminism, compared to Anglophone feminism, is distinguished by an approach which is more philosophical and literary. Its writings tend to be effusive and metaphorical being less concerned with political doctrine and generally focused on theories of “the body”. The term includes writers who are not French, but who have worked substantially in France and the French tradition such as Julia Kristeva and Bracha Ettinger.

The French author and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir wrote novels; monographs on philosophy, politics, and social issues; essays, biographies, and an autobiography. She is now best known for her metaphysical novels, including She Came to Stay and The Mandarins, and for her 1949 treatise The Second Sex, a detailed analysis of women’s oppression and a foundational tract of contemporary feminism. It sets out a feminist existentialism which prescribes a moral revolution. As an existentialist, she accepted Jean-Paul Sartre’s precept that existence precedes essence; hence “one is not born a woman, but becomes one”. Her analysis focuses on the social construction of Woman as the Other, this de Beauvoir identifies as fundamental to women’s oppression. She argues that women have historically been considered deviant and abnormal, and contends that even Mary Wollstonecraft considered men to be the ideal toward which women should aspire. De Beauvoir argues that for feminism to move forward, this attitude must be set aside.

In the 1970s French feminists approached feminism with the concept of écriture féminine (which translates as female, or feminine writing). Helene Cixous argues that writing and philosophy are phallocentric and along with other French feminists such as Luce Irigaray emphasize “writing from the body” as a subversive exercise. The work of the feminist psychoanalyst and philosopher, Julia Kristeva, has influenced feminist theory in general and feminist literary criticism in particular. From the 1980s onwards the work of the artist and psychoanalyst Bracha Ettinger has influenced literary criticism, art history and film theory., . However, as the scholar Elizabeth Wright points out, “none of these French feminists align themselves with the feminist movement as it appeared in the Anglophone world”.

Chapter- 3

Theoretical schools

Feminist theory is an extension of feminism into theoretical or philosophical fields. It encompasses work in a variety of disciplines, including anthropology, sociology, economics, women’s studies, literary criticism, art history, psychoanalysis and philosophy. Feminist theory aims to understand gender inequality and focuses on gender politics, power relations, and sexuality. While providing a critique of these social and political relations, much of feminist theory also focuses on the promotion of women’s rights and interests. Themes explored in feminist theory include discrimination, stereotyping, objectification (especially sexual objectification), oppression, and patriarchy.

The American literary critic and feminist Elaine Showalter describe the phased development of feminist theory. The first she calls “feminist critique”, in which the feminist reader examines the ideologies behind literary phenomena. The second Showalter calls “gynocriticism”, in which the “woman is producer of textual meaning” including “the psychodynamics of female creativity; linguistics and the problem of a female language; the trajectory of the individual or collective female literary career and literary history”. The last phase she calls “gender theory”, in which the “ideological inscription and the literary effects of the sex/gender system” are explored”. This model has been criticized by the scholar Toril Moi who sees it as an essentialist and deterministic model for female subjectivity and for failing to account for the situation of women outside the West.

Chapter- 4

Movements and ideologies

Several submovements of feminist ideology have developed over the years; some of the major subtypes are listed below. These movements often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several types of feminist thought.

4.1 Socialist and Marxist feminisms

Socialist feminism connects the oppression of women to Marxist ideas about exploitation, oppression and labor. Socialist feminists see women as being held down as a result of their unequal standing in both the workplace and the domestic sphere. Prostitution, domestic work, childcare, and marriage are all seen by socialist feminists as ways in which women are exploited by a patriarchal system which devalues women and the substantial work that they do. Socialist feminists focus their energies on broad change that affects society as a whole, rather than on an individual basis. They see the need to work alongside not just men, but all other groups, as they see the oppression of women as a part of a larger pattern that affects everyone involved in the capitalist system.

Marx felt that when class oppression was overcome, gender oppression would vanish as well. According to some socialist feminists, this view of gender oppression as a sub-class of class oppression is naive and much of the work of socialist feminists has gone towards separating gender phenomena from class phenomena. Some contributors to socialist feminism have criticized these traditional Marxist ideas for being largely silent on gender oppression except to subsume it underneath broader class oppression. Other socialist feminists, notably two long-lived American organizations Radical Women and the Freedom Socialist Party, point to the classic Marxist writings of Frederick Engels and August Bebel as a powerful explanation of the link between gender oppression and class exploitation.

In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century both Clara Zetkin and Eleanor Marx were against the demonization of men and supported a proletarian revolution that would overcome as many male-female inequalities as possible.

4.2 Radical feminism

Radical feminism considers the male controlled capitalist hierarchy, which it describes as sexist, as the defining feature of women’s oppression. Radical feminists believe that women can free themselves only when they have done away with what they consider an inherently oppressive and dominating patriarchal system. Radical feminists feel that there is a male-based authority and power structure and that it is responsible for oppression and inequality, and that as long as the system and its values are in place, society will not be able to be reformed in any significant way. Some radical feminists see no alternatives other than the total uprooting and reconstruction of society in order to achieve their goals.

Over time a number of sub-types of Radical feminism have emerged, such as Cultural feminism, Separatist feminism and Anti-pornography feminism. Cultural feminism is the ideology of a “female nature” or “female essence” that attempts to revalidate what they consider undervalued female attributes. It emphasizes the difference between women and men but considers that difference to be psychological, and to be culturally constructed rather than biologically innate. Its critics assert that because it is based on an essentialist view of the differences between women and men and advocates independence and institution building, it has led feminists to retreat from politics to “life-style” Once such critic, Alice Echols (a feminist historian and cultural theorist), credits Redstockings member Brooke Williams with introducing the term cultural feminism in 1975 to describe the depoliticisation of radical feminism.

Separatist feminism is a form of radical feminism that does not support heterosexual relationships. Its proponents argue that the sexual disparities between men and women are unresolvable. Separatist feminists generally do not feel that men can make positive contributions to the feminist movement and that even well-intentioned men replicate patriarchal dynamics. Author Marilyn Frye describes separatist feminism as “separation of various sorts or modes from men and from institutions, relationships, roles and activities that are male-defined, male-dominated, and operating for the benefit of males and the maintenance of male privilege – this separation being initiated or maintained, at will, by women”.

4.4 Liberal feminism

Liberal feminism asserts the equality of men and women through political and legal reform. It is an individualistic form of feminism, which focuses on women’s ability to show and maintain their equality through their own actions and choices. Liberal feminism uses the personal interactions between men and women as the place from which to transform society. According to liberal feminists, all women are capable of asserting their ability to achieve equality, therefore it is possible for change to happen without altering the structure of society. Issues important to liberal feminists include reproductive and abortion rights, sexual harassment, voting, education, “equal pay for equal work”, affordable childcare, affordable health care, and bringing to light the frequency of sexual and domestic violence against women.

4.5 Black feminism

Black feminism argues that sexism, class oppression, and racism are inextricably bound together. Forms of feminism that strive to overcome sexism and class oppression but ignore race can discriminate against many people, including women, through racial bias. The Combahee River Collective argued in 1974 that the liberation of black women entails freedom for all people, since it would require the end of racism, sexism, and class oppression. One of the theories that evolved out of this movement was Alice Walker’s Womanism. It emerged after the early feminist movements that were led specifically by white women who advocated social changes such as woman’s suffrage. These movements were largely white middle-class movements and had generally ignored oppression based on racism and classism. Alice Walker and other Womanists pointed out that black women experienced a different and more intense kind of oppression from that of white women.

Angela Davis was one of the first people who articulated an argument centered around the intersection of race, gender, and class in her book, Women, Race, and Class. Kimberle Crenshaw, a prominent feminist law theorist, gave the idea the name Intersectionality while discussing identity politics in her essay, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color”.

4.6 Postcolonial feminism and third-world feminism

Postcolonial feminists argue that oppression relating to the colonial experience, particularly racial, class, and ethnic oppression, has marginalized women in postcolonial societies. They challenge the assumption that gender oppression is the primary force of patriarchy. Postcolonial feminists object to portrayals of women of non-Western societies as passive and voiceless victims and the portrayal of Western women as modern, educated and empowered.

Postcolonial feminism emerged from the gendered history of colonialism: colonial powers often imposed Western norms on colonized regions. In the 1940s and 1950s, after the formation of the United Nations, former colonies were monitored by the West for what was considered “social progress”. The status of women in the developing world has been monitored by organizations such as the United Nations and as a result traditional practices and roles taken up by women—sometimes seen as distasteful by Western standards—could be considered a form of rebellion against colonial oppression. Postcolonial feminists today struggle to fight gender oppression within their own cultural models of society rather than through those imposed by the Western colonizers.

Postcolonial feminism is critical of Western forms of feminism, notably radical feminism and liberal feminism and their universalization of female experience. Postcolonial feminists argue that cultures impacted by colonialism are often vastly different and should be treated as such. Colonial oppression may result in the glorification of pre-colonial culture, which, in cultures with traditions of power stratification along gender lines, could mean the acceptance of, or refusal to deal with, inherent issues of gender inequality. Postcolonial feminists can be described as feminists who have reacted against both universalizing tendencies in Western feminist thought and a lack of attention to gender issues in mainstream postcolonial thought.

Third-world feminism has been described as a group of feminist theories developed by feminists who acquired their views and took part in feminist politics in so-called third-world countries. Although women from the third world have been engaged in the feminist movement, Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Sarojini Sahoo criticize Western feminism on the grounds that it is ethnocentric and does not take into account the unique experiences of women from third-world countries or the existence of feminisms indigenous to third-world countries. According to Chandra Talpade Mohanty, women in the third world feel that Western feminism bases its understanding of women on “internal racism, classism and homophobia”. This discourse is strongly related to African feminism and postcolonial feminism. Its development is also associated with concepts such as black feminism, womanism, “Africana womanism”, “motherism”, “Stiwanism”, “negofeminism”, chicana feminism, and “femalism”.

4.7 Multiracial feminism

Multiracial feminism (also known as “women of color” feminism) offers a standpoint theory and analysis of the lives and experiences of women of color. The theory emerged in the 1990s and was developed by Dr. Maxine Baca Zinn, a Chicana feminist and Dr. Bonnie Thornton Dill, a sociology expert on African American women and family.

4.8 Libertarian feminism

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “Classical liberal or libertarian feminism conceives of freedom as freedom from coercive interference. It holds that women, as well as men, have a right to such freedom due to their status as self-owners.”

There are several categories under the theory of libertarian feminism, or kinds of feminism that are linked to libertarian ideologies. Anarcha-feminism (also called anarchist feminism or anarcho-feminism) combines feminist and anarchist beliefs, embodying classical libertarianism rather than contemporary conservative libertarianism. Anarcha-feminists view patriarchy as a manifestation of hierarchy, believing that the fight against patriarchy is an essential part of the class struggle and the anarchist struggle against the state. Anarcha-feminists such as Susan Brown see the anarchist struggle as a necessary component of the feminist struggle. In Brown’s words, “anarchism is a political philosophy that opposes all relationships of power, it is inherently feminist”. Recently, Wendy McElroy has defined a position (which she labels “ifeminism” or “individualist feminism”) that combines feminism with anarcho-capitalism or contemporary conservative libertarianism, arguing that a pro-capitalist, anti-state position is compatible with an emphasis on equal rights and empowerment for women. Individualist anarchist-feminism has grown from the US-based individualist anarchism movement.

Individualist feminism is typically defined as a feminism in opposition to what writers such as Wendy McElroy and Christina Hoff Sommers term, political or gender feminism. However, there are some differences within the discussion of individualist feminism. While some individualist feminists like McElroy oppose government interference into the choices women make with their bodies because such interference creates a coercive hierarchy (such as patriarchy), other feminists such as Christina Hoff Sommers hold that feminism’s political role is simply to ensure that everyone’s, including women’s, right against coercive interference is respected.] Sommers is described as a “socially conservative equity feminist” by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and she has argued that women should voluntarily commit to traditional gender roles. Critics have called her an anti-feminist.

4.9 Post-structural and postmodern feminism

Post-structural feminism, also referred to as French feminism, uses the insights of various epistemological movements, including psychoanalysis, linguistics, political theory (Marxist and post-Marxist theory), race theory, literary theory, and other intellectual currents for feminist concerns. Many post-structural feminists maintain that difference is one of the most powerful tools that females possess in their struggle with patriarchal domination, and that to equate the feminist movement only with equality is to deny women a plethora of options because equality is still defined from the masculine or patriarchal perspective.

Postmodern feminism is an approach to feminist theory that incorporates postmodern and post-structuralist theory. The largest departure from other branches of feminism is the argument that gender is constructed through language. The most notable proponent of this argument is Judith Butler. In her 1990 book, Gender Trouble, she draws on and critiques the work of Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan. Butler criticizes the distinction drawn by previous feminisms between biological sex and socially constructed gender. She says that this does not allow for a sufficient criticism of essentialism. For Butler “woman” is a debatable category, complicated by class, ethnicity, sexuality, and other facets of identity. She suggests that gender is performative. This argument leads to the conclusion that there is no single cause for women’s subordination and no single approach towards dealing with the issue.

In A Cyborg Manifesto Donna Haraway criticizes traditional notions of feminism, particularly its emphasis on identity, rather than affinity. She uses the metaphor of a cyborg in order to construct a postmodern feminism that moves beyond dualisms and the limitations of traditional gender, feminism, and politics. Haraway’s cyborg is an attempt to break away from Oedipal narratives and Christian origin-myths like Genesis. She writes: “The cyborg does not dream of community on the model of the organic family, this time without the oedipal project. The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust.”

A major branch in postmodern feminist thought has emerged from the contemporary psychoanalytic French feminism. Other postmodern feminist works highlight stereotypical gender roles, only to portray them as parodies of the original beliefs. The history of feminism is not important in these writings—only what is going to be done about it. The history is dismissed and used to depict how ridiculous past beliefs were. Modern feminist theory has been extensively criticized as being predominantly, though not exclusively, associated with Western middle class academia. Mary Joe Frug, a postmodernist feminist, criticized mainstream feminism as being too narrowly focused and inattentive to related issues of race and class.

4.10 Ecofeminism

Ecofeminism links ecology with feminism. Ecofeminists see the domination of women as stemming from the same ideologies that bring about the domination of the environment. Patriarchal systems, where men own and control the land, are seen as responsible for the oppression of women and destruction of the natural environment. Ecofeminists argue that the men in power control the land, and therefore they are able to exploit it for their own profit and success. Ecofeminists argue that in this situation, women are exploited by men in power for their own profit, success, and pleasure. Ecofeminists argue that women and the environment are both exploited as passive pawns in the race to domination. Ecofeminists argue that those people in power are able to take advantage of them distinctly because they are seen as passive and rather helpless. Ecofeminism connects the exploitation and domination of women with that of the environment. As a way of repairing social and ecological injustices, ecofeminists feel that women must work towards creating a healthy environment and ending the destruction of the lands that most women rely on to provide for their families.

Ecofeminism argues that there is a connection between women and nature that comes from their shared history of oppression by a patriarchal Western society. Vandana Shiva claims that women have a special connection to the environment through their daily interactions with it that has been ignored. She says that “women in subsistence economies, producing and reproducing wealth in partnership with nature, have been experts in their own right of holistic and ecological knowledge of nature’s processes. But these alternative modes of knowing, which are oriented to the social benefits and sustenance needs are not recognized by the capitalist reductionist paradigm, because it fails to perceive the interconnectedness of nature, or the connection of women’s lives, work and knowledge with the creation of wealth.”

However, feminist and social ecologist Janet Biehl has criticized ecofeminism for focusing too much on a mystical connection between women and nature and not enough on the actual conditions of women.

Chapter- 5

Feminist sociology

Feminist sociology approaches sociology by observing gender and its role in social structure.

Feminist sociology studies the current climate of feminism in relation to all other interactions of society. Feminism is in its third wave of thought, and this is reflected in feminist ideology by the current awareness of differences in women throughout the world. In the previous waves of feminism, only the needs of a specific type of women were addressed.[] In third wave feminism, feminists have attempted to stop making generalizations of all women, and instead, have focused on the needs of their gender with intersection of sexual orientation, race, economic status, and nationality differences among women. Third wave looks to give voices to the women who have gone unheard throughout the previous waves of the feminist movement. As a result, other issues have arisen within feminist sociology.

5.1 Oppression

The core element to the feminist movement and feminist sociology is the idea of systematic oppression against women. Feminist sociologists argue that this oppression exists and is essentially due to patriarchal systems that they claim exist in society. The basic theory of oppression is that all women, no matter where they live or what religion, race, or social status they possess, are oppressed due to their sex. Oppression can overlap if women are in other oppressed groups, such as a race that is oppressed or a sexuality that is oppressed within a certain society. These overlapping oppressed identities can create issue of which oppression to fight and which to accept.

5.2 Sexism and sex politics

People are socialized to give a certain degree of respect and power to a person based solely on his or her appearance. In most societies, this is true for age and race, as well as sex. When someone encounters another person, one of the first things he or she will do is to try to determine whether this person is male or female. Cues varying from a person’s clothes to physical features to voice could cue a person to what sex someone is. Because this is one of the first things that happen when an encounter is made, sex is a status category with political implications. A person has to determine what sex a person is in order to know how he or she should address him or her. Sexism has been defined as any cultural or economic structure which creates or enforces the patterns of sex-marking, which divide the species into dominates and subordinates.

5.3 Language (English)

Certain words have become commonly attributed to each sex. This is a result of socialization and gender power structures and has no true basis in biology or gender differences.

Male versus Female

Aggressive versus Passive

Intelligent versus Ignorant

Outspoken versus Quiet

Emotionless versus Emotional

Strong versus Weak

Virile versus Virtuous

Detached versus Nurturing

This language affects not only everyday speech, but also finds its way into academic arenas such as science, which in turn creates a new type socialization that is potentially more dangerous due to its covert infiltration of an educational and academic setting that is supposed to be unbiased. A classic example of this is how the process of fertilization is commonly described in textbooks and other scientific sources of information. Cultural stereotypes about gender have affected and biased society’s ideas about the egg and the sperm. Writers of textbooks in the past have put the sperm on a hero’s quest to conquer, penetrate, and overpower the helpless and passive egg.

The feminist movement has been criticized in the past for catering to issue of primarily white, heterosexual, middle class women, ignoring the needs of women of color, lesbians and bisexuals, and women of lower class.

5.4 Heterosexism

At one point, heterosexual marriage was the only lawful union between two people that was recognized and given full benefits in the United States. This clearly put homosexual couples of both sexes at a disadvantage, making their relationships less valid in the eyes of the government than that of a relationship between a man and a woman.

States in the US regulate “many aspects of marriage law affecting the day to day lives of inhabitants of the United States are determined by the states, not the federal government, and the Defense of Marriage Act does not prevent individual states from defining marriage as they see fit.”

Massachusetts has recognized same-sex marriage since 2004. Connecticut, Vermont, New Jersey, California, and New Hampshire have created legal unions that, while not called marriages, are explicitly defined as offering all the rights and responsibilities of marriage under state law to same-sex couples. Maine, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, Oregon and Washington have created legal unions for same-sex couples that offer varying subsets of the rights and responsibilities of marriage under the laws of those jurisdictions.

5.5 Feminism and race

Feminism and race sometimes seem to be at odds. Women who already suffer from oppression due to their race find themselves in a double bind. They are forced to choose between backing issues important to their race and betraying their sex, or backing issues important to women and betraying their race. Feminists who are not oppressed due to their race have overlooked this issue in the past.

5.6 Feminism and culture/religion

The question has been raised as to whether it is possible to be a feminist and a multiculturalist at the same time. The reason this is an issue is because there are conflicting factors on certain stances. Some practices that are carried out by cultures or religions are clearly not beneficial and are oppressive to women. But a multiculturalist would argue that a culture should not go in and attempt to insert its own ideals and beliefs on another culture.

5.6.1 Marriage

In some cultures, women are forced into arranged marriages according to the cultural customs of their region or their religion. Taking away a woman’s right to choose a life partner would clearly be an issue with feminists.

5.6.2 Rape/ Infidelity and Honor Killings

Some cultures punish women after a rape has occurred, claiming that her impurity has brought shame on the family. Women are also tortured or killed in other cultures throughout the world for infidelities that bring shame to the family.

5.6.3 Mutilation

In various cultures throughout the world, female genital mutilation (FGM) is a cultural practice that has been allowed and even encouraged to occur. If a woman has not undergone FGM, she is thought to be unclean and un-marriageable in her culture.

Chapter- 6

Religion

Feminist theology is a movement that reconsiders the traditions, practices, scriptures, and theologies of religions from a feminist perspective. Some of the goals of feminist theology include increasing the role of women among the clergy and religious authorities, reinterpreting male-dominated imagery and language about God, determining women’s place in relation to career and motherhood, and studying images of women in the religion’s sacred texts.

6.1 Christian feminism:

Christian feminism is a branch of feminist theology which seeks to interpret and understand Christianity in light of the equality of women and men. Because this equality has been historically ignored, Christian feminists believe their contributions are necessary for a complete understanding of Christianity. While there is no standard set of beliefs among Christian feminists, most agree that God does not discriminate on the basis of biologically-determined characteristics such as sex. Their major issues are the ordination of women, male dominance in Christian marriage, and claims of moral deficiency and inferiority of abilities of women compared to men. They also are concerned with the balance of parenting between mothers and fathers and the overall treatment of women in the church.

6.2 Islamic feminism:

Islamic feminism is concerned with the role of women in Islam and aims for the full equality of all Muslims, regardless of gender, in public and private life. Islamic feminists advocate women’s rights, gender equality, and social justice grounded in an Islamic framework. Although rooted in Islam, the movement’s pioneers have also utilized secular and Western feminist discourses and recognize the role of Islamic feminism as part of an integrated global feminist movement. Advocates of the movement seek to highlight the deeply rooted teachings of equality in the Quran and encourage a questioning of the patriarchal interpretation of Islamic teaching through the Quran, hadith (sayings of Muhammad), and sharia (law) towards the creation of a more equal and just society.

6.3 Jewish feminism:

Jewish feminism is a movement that seeks to improve the religious, legal, and social status of women within Judaism and to open up new opportunities for religious experience and leadership for Jewish women. Feminist movements, with varying approaches and successes, have opened up within all major branches of Judaism. In its modern form, the movement can be traced to the early 1970s in the United States. According to Judith Plaskow, who has focused on feminism in Reform Judaism, the main issues for early Jewish feminists in these movements were the exclusion from the all-male prayer group or minyan, the exemption from positive time-bound mitzvot, and women’s inability to function as witnesses and to initiate divorce.

6.4 The Dianic Wicca or Wiccan feminism:

The Dianic Wicca or Wiccan feminism is a female focused, Goddess-centered Wiccan sect; also known as a feminist religion that teaches witchcraft as every woman’s right. It is also one sect of the many practiced in Wicca.

Chapter- 7

Culture

7.1 Women’s writing

Women’s writing came to exist as a separate category of scholarly interest relatively recently. In the West, second-wave feminism prompted a general reevaluation of women’s historical contributions, and various academic sub-disciplines, such as Women’s history (or herstory) and women’s writing, developed in response to the belief that women’s lives and contributions have been underrepresented as areas of scholarly interest. Virginia Balisn et al. characterize the growth in interest since 1970 in women’s writing as “powerful”. Much of this early period of feminist literary scholarship was given over to the rediscovery and reclamation of texts written by women. Studies such as Dale Spender’s Mothers of the Novel (1986) and Jane Spencer’s The Rise of the Woman Novelist (1986) were ground-breaking in their insistence that women have always been writing. Commensurate with this growth in scholarly interest, various presses began the task of reissuing long-out-of-print texts. Virago Press began to publish its large list of nineteenth and early-twentieth-century novels in 1975 and became one of the first commercial presses to join in the project of reclamation. In the 1980s Pandora Press, responsible for publishing Spender’s study, issued a companion line of eighteenth-century novels written by women. More recently, Broadview Press has begun to issue eighteenth- and nineteenth-century works, many hitherto out of print and the University of Kentucky has a series of republications of early women’s novels. There has been commensurate growth in the area of biographical dictionaries of women writers due to a perception, according to one editor, that “most of our women are not represented in the ‘standard’ reference books in the field”.

Another early pioneer of Feminist writing is Charlotte Perkins Gilman, whose most notable work was The Yellow Wallpaper.

7.1.1 Feminist science fiction

In the 1960s the genre of science fiction combined its sensationalism with political and technological critiques of society. With the advent of feminism, questioning women’s roles became fair game to this “subversive, mind expanding genre”. Two early texts are Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and Joanna Russ’ The Female Man (1970). They serve to highlight the socially constructed nature of gender roles by creating utopias that do away with gender. Both authors were also pioneers in feminist criticism of science fiction in the 1960s and 70s, in essays collected in The Language of the Night (Le Guin, 1979) and How To Suppress Women’s Writing (Russ, 1983). Another major work of feminist science fiction has been Kindred by Octavia Butler.

7.2 Riot grrrl movement

Riot grrrl (or riot grrl) is an underground feminist punk movement that started in the 1990s and is often associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). It was Grounded in the DIY philosophy of punk values. Riot grrls took an anti-corporate stance of self-sufficiency and self-reliance. Riot grrrl’s emphasis on universal female identity and separatism often appears more closely allied with second-wave feminism than with the third wave. Riot grrrl bands often address issues such as rape, domestic abuse, sexuality, and female empowerment. Some bands associated with the movement are: Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Excuse 17, Free Kitten, Heavens To Betsy, Huggy Bear, L7, and Team Dresch. In addition to a music scene, riot grrrl is also a subculture; zines, the DIY ethic, art, political action, and activism are part of the movement. Riot grrrls hold meetings, start chapters, and support and organize women in music.

The riot grrrl movement sprang out of Olympia, Washington and Washington, D.C. in the early 1990s. It sought to give women the power to control their voices and artistic expressions. Riot grrrls took a growling double or triple r, placing it in the word girl as a way to take back the derogatory use of the term.

The Riot Grrrl’s links to social and political issues are where the beginnings of third-wave feminism can be seen. The music and zine writings are strong examples of “cultural politics in action, with strong women giving voice to important social issues though an empowered, a female oriented community, many people link the emergence of the third-wave feminism to this time”. The movement encouraged and made “adolescent girls’ standpoints central,” allowing them to express themselves fully.

Chapter- 8

Pornography

The “Feminist Sex Wars” is a term for the acrimonious debates within the feminist movement in the late 1970s through the 1980s around the issues of feminism, sexuality, sexual representation, pornography, sadomasochism, the role of transwomen in the lesbian community, and other sexual issues. The debate pitted anti-pornography feminism against sex-positive feminism, and parts of the feminist movement were deeply divided by these debates.

8.1 Anti-pornography movement

Anti-pornography feminists, such as Catharine MacKinnon, Andrea Dworkin, Robin Morgan and Dorchen Leidholdt, put pornography at the center of a feminist explanation of women’s oppression.

Some feminists, such as Diana Russell, Andrea Dworkin, Catharine MacKinnon, Susan Brownmiller, Dorchen Leidholdt, Ariel Levy, and Robin Morgan, argue that pornography is degrading to women, and complicit in violence against women both in its production (where, they charge, abuse and exploitation of women performing in pornography is rampant) and in its consumption (where, they charge, pornography eroticizes the domination, humiliation, and coercion of women, and reinforces sexual and cultural attitudes that are complicit in rape and sexual harassment).

Beginning in the late 1970s, anti-pornography radical feminists formed organizations such as Women Against Pornography that provided educational events, including slide-shows, speeches, and guided tours of the sex industry in Times Square, in order to raise awareness of the content of pornography and the sexual subculture in pornography shops and live sex shows. Andrea Dworkin and Robin Morgan began articulating a vehemently anti-porn stance based in radical feminism beginning in 1974, and anti-porn feminist groups, such as Women Against Pornography and similar organizations, became highly active in various US cities during the late 1970s.

8.2 Sex-positive movement

Sex-positive feminism is a movement that was formed in order to address issues of women’s sexual pleasure, freedom of expression, sex work, and inclusive gender identities. Ellen Willis’ 1981 essay, “Lust Horizons: Is the Women’s Movement Pro-Sex?” is the origin of the term, “pro-sex feminism”; the more commonly-used variant, “sex positive feminism” arose soon after.

Although some sex-positive feminists, such as Betty Dodson, were active in the early 1970s, much of sex-positive feminism largely began in the late 1970s and 1980s as a response to the increasing emphasis in radical feminism on anti-pornography activism, and to the ideas of anti-pornography feminists like Robin Morgan, Andrea Dworkin, and Catharine MacKinnon, who argued that sexual expressions such as pornography, sadomasochism, transexualism, and other “male” modes of sexuality are a central cause of women’s oppression.

Sex-positive feminists are also strongly opposed to radical feminist calls for legislation against pornography, a strategy they decried as censorship, and something that could, they argued, be used by social conservatives to censor the sexual expression of women, gay people, and other sexual minorities. The initial period of intense debate and acrimony between sex-positive and anti-pornography feminists during the early 1980s is often referred to as the Feminist Sex Wars. Other sex-positive feminists became involved not in opposition to other feminists, but in direct response to what they saw as patriarchal control of sexuality.

Chapter- 9

Relationship to Political Movements

9.1 Socialism

Since the early twentieth century some feminists have allied with socialism. In 1907 there was an International Conference of Socialist Women in Stuttgart where suffrage was described as a tool of class struggle. Clara Zetkin of the Social Democratic Party of Germany called for women’s suffrage to build a “socialist order, the only one that allows for a radical solution to the women’s question”.

In Britain, the women’s movement was allied with the Labour party. In America, Betty Friedan emerged from a radical background to take command of the organized movement. Radical Women, founded in 1967 in Seattle is the oldest (and still active) socialist feminist organization in the U.S. During the Spanish Civil War, Dolores Ibárruri (La Pasionaria) led the Communist Party of Spain. Although she supported equal rights for women, she opposed women fighting on the front and clashed with the anarcho-feminist Mujeres Libres.

Revolutions in Latin America brought changes in women’s status in countries such as Nicaragua where Feminist ideology during the Sandinista Revolution was largely responsible for improvements in the quality of life for women but fell short of achieving a social and ideological change.

9.2 Fascism

Scholars have argued that Nazi Germany and the other fascist states of the 1930s and 1940s illustrates the disastrous consequences for society of a state ideology that, in glorifying women, becomes anti-feminist. In Germany after the rise of Nazism in 1933, there was a rapid dissolution of the political rights and economic opportunities that feminists had fought for during the prewar period and to some extent during the 1920s. In Franco’s Spain, the right wing Catholic conservatives undid the work of feminists during the Republic. Fascist society was hierarchical with an emphasis and idealization of virility, with women maintaining a largely subordinate position to men.

Chapter- 10

Scientific Discourse

Some feminists are critical of traditional scientific discourse, arguing that the field has historically been biased towards a masculine perspective. Evelyn Fox Keller argues that the rhetoric of science reflects a masculine perspective, and she questions the idea of scientific objectivity. Primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy notes the prevalence of masculine-coined stereotypes and theories, such as the non-sexual female, despite “the accumulation of abundant openly available evidence contradicting it”. Some natural and social scientists have examined feminist ideas using scientific methods.

10.1 Biology of gender

Modern feminist science is based on the view that many differences between the sexes are based on socially constructed gender identities rather than on biological sex differences. For example, Anne Fausto-Sterling’s book Myths of Gender explores the assumptions embodied in scientific research that purports to support a biologically essentialist view of gender. Her second book, Sexing the Body discussed the biological possibility of more than two true biological sexes. However, in The Female Brain, Louann Brizendine argues that brain differences between the sexes are a biological reality with significant implications for sex-specific functional differences. Steven Rhoads’ book Taking Sex Differences Seriously illustrates sex-dependent differences across a wide scope.

Carol Tavris, in The Mismeasure of Woman, uses psychology and sociology to critique theories that use biological reductionism to explain differences between men and women. She argues rather than using evidence of innate gender difference there is an over-changing hypothesis to justify inequality and perpetuate stereotypes.

10.2 Evolutionary biology

Sarah Kember—drawing from numerous areas such as evolutionary biology, sociobiology, artificial intelligence, and cybernetics in development with a new evolutionism—discusses the biologization of technology. She notes how feminists and sociologists have become suspect of evolutionary psychology, particularly inasmuch as sociobiology is subjected to complexity in order to strengthen sexual difference as immutable through pre-existing cultural value judgments about human nature and natural selection. Where feminist theory is criticized for its “false beliefs about human nature,” Kember then argues in conclusion that “feminism is in the interesting position of needing to do more biology and evolutionary theory in order not to simply oppose their renewed hegemony, but in order to understand the conditions that make this possible, and to have a say in the construction of new ideas and artefacts.”

Chapter-11

Men and feminism

The relationship between men and feminism has been complex. Men have taken part in significant responses to feminism in each ‘wave’ of the movement. There have been positive and negative reactions and responses, depending on the individual man and the social context of the time. These responses have varied from pro-feminism to masculism to anti-feminism. In the twenty-first century new reactions to feminist ideologies have emerged including a generation of male scholars involved in gender studies, and also men’s rights activists who promote male equality (including equal treatment in family, divorce and anti-discrimination law). Historically a number of men have engaged with feminism. Philosopher Jeremy Bentham demanded equal rights for women in the eighteenth century. In 1866, philosopher John Stuart Mill (author of “The Subjection of Women”) presented a women’s petition to the British parliament; and supported an amendment to the 1867 Reform Bill. Others have lobbied and campaigned against feminism. Today, academics like Michael Flood, Michael Messner and Michael Kimmel are involved with men’s studies and pro-feminism. Significant weaknesses in the work of Kimmel have been identified by former director of the National Organisation of Women (NOW) Warren Farrell. In identifying the nature and impacts of matriarchy, and counter-posing these to patriarchy, Farrell has been at the fore-front of arguing that the feminism of the 1960s/1970s was subverted by a women’s right movement in the 1980s and 1990s. A further development of Farrell’s work has resulted in Attraction Theory, as a way of explaining the reproduction of both patriarchy and matriarchy at work and home. In significant ways, this theory picks up the argument made by Betty Friedan in The Second Stage that men will be at the forefront of further equality movements.

A number of feminist writers maintain that identifying as a feminist is the strongest stand men can take in the struggle against sexism. They have argued that men should be allowed, or even be encouraged, to participate in the feminist movement. Other female feminists argue that men cannot be feminists simply because they are not women. They maintain that men are granted inherent privileges that prevent them from identifying with feminist struggles, thus making it impossible for them to identify with feminists. Fidelma Ashe has approached the issue of male feminism by arguing that traditional feminist views of male experience and of “men doing feminism” have been monolithic. She explores the multiple political discourses and practices of pro-feminist politics, and evaluates each strand through an interrogation based upon its effect on feminist politics.

Chapter-12

Pro-feminism

Pro-feminism refers to support of the cause of feminism without implying that the supporter is a member of the feminist movement. The term is most often used in reference to men who are actively supportive of feminism and of efforts to bring about gender equality. A number of pro-feminist men are involved in political activism, most often in the areas of women’s rights and violence against women.

As feminist theory found support among a number of men who formed consciousness-raising groups in the 1960s, these groups were differentiated by preferences for particular feminisms and political approaches. However, the inclusion of men’s voices as “feminists” presented issues for some. For a number of women and men, the word “feminism” was reserved for women, the subjects who experienced the inequality and oppression that feminism sought to address.

There are pro-feminist men’s groups in most nations in the Western world. The activities of pro-feminist men’s groups include anti-violence work with boys and young men in schools, offering sexual harassment workshops in workplaces, running community education campaigns, and counseling male perpetrators of violence.

Pro-feminist men also are involved in men’s health, men’s studies, the development of gender equity curricula in schools, and many other areas. Pro-feminist men who support sex-negative feminists participate in activism against pornography including anti-pornography legislation.

This work is sometimes in collaboration with feminists and women’s services, such as domestic violence and rape crisis centers.

The term “pro-feminist” is also sometimes used by people who hold feminist beliefs or who advocate on behalf of feminist causes, but who do not consider themselves to be feminists. Some activists of both genders will not refer to men as “feminists” at all, and will refer to all pro-feminist men as “pro-feminists”, even if the men in question refer to themselves as “feminists”. There is also criticism from the ‘other side’ against “pro-feminist” men who refuse to identify as feminist. Most major feminist groups, most notably the National Organization for Women and the Feminist Majority Foundation, refer to male activists as feminists rather than as pro-feminists.

Chapter-13

Anti-feminism

Anti-feminism is opposition to feminism in some or all of its forms.[188] Writers such as Camille Paglia, Christina Hoff Sommers, Jean Bethke Elshtain and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese have been labeled “anti-feminists” by other feminists. Daphne Patai and Noretta Koertge argue that in this way the term “anti-feminist” is used to silence academic debate about feminism. Paul Nathanson and Katherine K. Young’s books Spreading Misandry and Legalizing Misandry explore what they argue is feminist-inspired misandry. Christina Hoff-Sommers argues feminist misandry leads directly to misogyny by what she calls “establishment feminists” against (the majority of) women who love men in Who Stole Feminism: How Women Have Betrayed Women. “Marriage rights” advocates criticize feminists like Sheila Cronan who take the view that marriage constitutes slavery for women, and that freedom for women cannot be won without the abolition of marriage.

13.1 Antifeminist claims and ideas

Many antifeminist proponents say the feminist movement has achieved its aims and now seeks higher status for women than for men.

Others consider feminism a destructive force that endangers the family. For example, political scientist Paul Gottfried describes this antifeminist position:

Serious conservative scholars like Allan Carlson and F. Carolyn Graglia have maintained that the change of women’s role, from being primarily mothers to self-defined professionals, has been a social disaster that continues to take its toll on the family. Rather than being the culminating point of Western Christian gentility, the movement of women into commerce and politics may be seen as exactly the opposite, the descent by increasingly disconnected individuals into social chaos.

Antifeminist writer Jim Kalb describes the stance thus:

To be antifeminist is simply to accept that men and women differ and rely on each other to be different, and to view the differences as among the things constituting human life that should be reflected where appropriate in social attitudes and institutions. By feminist standards all societies have been thoroughly sexist. It follows that to be antifeminist is only to abandon the bigotry of a present-day ideology that sees traditional relations between the sexes as simply a matter of domination and submission, and to accept the validity of the ways in which human beings have actually dealt with sex, children, family life and so on. Antifeminism is thus nothing more than the rejection of one of the narrow and destructive fantasies of an age in which such things have been responsible for destruction and murder on an unprecedented scale.

Antifeminists often decry what they view as the misandric policies of Western governments, including anti-male discrimination in the areas of reproductive rights, child custody, alimony, and property division in divorce, pointing to statistical figures. As well they object to “affirmative action,” which they usually refer to as “positive discrimination,” against men and women in the form of quotas in the areas of employment, education, politics, and healthcare.

Antifeminists sometimes point to an increase in divorce and “family breakdown” and attribute as its cause the influence of feminism. They also cite that crime, teenage pregnancy, and drug abuse are higher among children of fatherless homes, considering that 66-80% (depending on the source) of divorces are initiated by women and that single mothers are accountable for 49% of all child abuse cases.

Furthermore, antifeminists argue that feminist organizations and researchers frequently use fake statistical data and research..

Antifeminist comments periodically appear in U.S. political punditry. For example, in a 1983 syndicated column, Pat Buchanan wrote, “Rail as they will about discrimination, women are simply not endowed by nature with the same measures of single-minded ambition and the will to succeed in the fiercely competitive world of Western capitalism.”

Antifeminists say that feminists impose tremendous pressure on traditional women by denigrating the role of a traditional housewife: “No woman should be authorized to stay at home to raise her children. Society should be totally different. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.” Instead promoting the business woman, woman leader models, as well encouraging women into competitive environments, where they may not be able to perform as well as males, if only for purely physical reasons. A case well illustrated by Taylor Caldwell:

There is no solid satisfaction in any career for a woman like myself. There is no home, no true freedom, no hope, no joy, no expectation for tomorrow, no contentment. I would rather cook a meal for a man and bring him his slippers and feel myself in the protection of his arms than have all the citations and awards and honors I have received worldwide, including the Ribbon of Legion of Honor and my property and my bank accounts. They mean nothing to me. And I am only one among the millions of sad women like myself. “Ask Them Yourself”

Antifeminists furthermore point out cases when feminist policies and regulations are detrimental to female self-esteem. For example, women sometimes receive “special treatment” in the form of lower physical requirements in some professions such as military and rescue services. Women who are hired are expected to handle less physically demanding tasks, which may reduce effectiveness of a unit. These policies make it impossible to refuse hiring women.

13.2 Antifeminist Leaders

Feminists such as Camille Paglia, Christina Hoff Sommers, Jean Bethke Elshtain and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese have been labeled “antifeminists”, or holders of antifeminist views, by other feminists because of their positions regarding oppression and lines of thought within feminism (which Sommers has controversially defined as gender feminism). Authors Patai and Koerge argue that in this way the term “antifeminist” is used to silence academic debate about feminism, and represents “an enormous extension of women’s power, allowing any sort of criticism of either women or feminist ideas to fall under the watchful eye of their ideological guardians.”

Other feminists such as media critic Jennifer Pozner claim that Paglia, Sommers, Elshtain and Fox-Genovese use the feminist label as a ruse. In describing what she believes is a method of so-called “rebel feminists” who use “Leftist lingo to gain rebellious credibility in a supposedly politically correct culture,” she identifies what she argues is a contradiction: “[they] [b]ecome vocally indignant at [other feminists] refusal to tolerate [their] ‘dissenting feminist voice'” and then “[g]o directly to the media. Do not pass up the college lecture circuit. Do not turn down close to $200K in Right Wing grants” and wait “for the money to come rolling in.” She goes on to further counter claims of silencing debate or criticism: “Use your role as ‘rebel feminist’ to denounce every feminist concern other than women’s economic advancement.” and “(…) substantiate your claims by using faulty research methods and superficial interviews. Rarely contact the authors, activists and psychologists you libel.”

Pozner writes:

“Anti-feminist women who attack feminism under the guise of the liberal cause of women’s advancement are far less easy to dismiss than right-wing critics such as Phyllis Schlafly or Rush Limbaugh. Yet Schlafly and Sommers are both listed in the speakers guide of the Young Americas Foundation, a group which routinely gives $10K grants to student groups to bring conservative lecturers to their campuses. Sommers is also a speaker for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, another right think tank, which dishes out the dollars to sponsor lecturers who “counter the Marxists, radical feminists, deconstructionists, and other ‘politically correct’ types on your campus.” The media seize the rhetoric of self-proclaimed “feminist dissenters” such as Sommers and Rophie as proof that feminism is failing women (“See,” we are supposed to think, “even the feminists now admit their movement is passé”). They are compensated highly for their complicity: Sommers received over $164,000 in grants from the conservative Olin, Bradley and Carthage foundations for “Who Stole Feminism”, in addition to a six-figure advance from her publisher, Simon and Schuster.”

13.3 Critique of Antifeminism

Some criticism of antifeminism has focused on studies of the behavior of children from fatherless homes, labeling them misleading and alarmist.

Research on the impact of father involvement on children provides evidence that high levels of paternal participation tends to increase children’s cognitive competence, empathy, and internal locus of control. These children are also characterized by reduced sex-stereotyped beliefs. However, these positive outcomes may result because the fathers sampled wanted to be and enjoyed being involved in childcare, not just because they were involved per se.

Australian sociologist Michael Flood argues that although children of two-parent families generally do better psychologically and educationally than children of single-parent families, that does not necessarily mean that correlation between these two factors implies that one is the cause of the other, and that neither divorce, nor fatherlessness in themselves are the cause of it. In a discussion paper he uses studies to argue that it is the quality of parenting and the child’s relationship with the parents that plays the main role. That children are negatively influenced by the situations in families characterized by violence, psychological problems, substance abuse, or economic insecurity and that it is the couples where such situations are frequent that are more likely to get divorced.

In an article in American Psychologist (June 1999), Louise B. Silverstein and Carl F. Auerbach conclude that “the stability of the emotional connection and the predictability of the caretaking relationship are the significant variables that predict positive child adjustment.” They also state that “a wide variety of family structures can support positive child outcomes.”

13.4 Antifeminist organizations

As of 2008 the most successful antifeminist organization in the US is STOP ERA, founded by Phyllis Schlafly in October 1972. Schlafly successfully mobilised thousands of people to block the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment in the USA. It was Schlafly too who forged links between STOP ERA and other conservative organizations, as well as single-issue groups against abortion, pornography, gun control, and unions. By integrating STOP ERA with the so-called New Right she was able to leverage a wider range of technological, organisational and political resources, successfully targeting pro-feminist candidates for defeat.