ABSTRACT –

Models or frameworks of opinion leadership normally start with opinion leadership and postulate about its impact on recipients and on the success of new products. Researchers have been less interested in modeling opinion leadership itself. This paper examines the opinion leadership literature to determine how consumer behavior researchers have viewed opinion leadership at the sender level and identifies the model implicit in their work. This implicit model is expanded and tested empirically.

INTRODUCTION:

The importance of interpersonal communication in consumer decision processes has been documented again and again in consumer behavior research, with numerous studies describing the frequency of consumer word-of-mouth and its influence on recipients (Arndt 1967; Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Leonard-Barton 1985; Technical Assistance Research Programs 1981). Even in this era of mass communications and mass advertising, it has been estimated that as much as 80% of all buying decisions are influenced by someone’s direct recommendation (Voss 1984).

Opinion leaders are credited with a large amount of this interpersonal communication, and considerable research resources have been directed at identifying the demographic and social characteristics of opinion leaders (e.g. Myers and Robertson 1972; Summers 1970). Much less effort has been directed at identifying the motives underlying opinion leadership or understanding why opinion leadership occurs at all. In one of the few studies on this topic, Dichter (1966) suggested that involvement with the product class is an important determinant of word-of-mouth. While Dichter’s analysis has stimulated little further research, a few early studies of opinion leadership that examined a potpourri of consumer variables found significant correlations between opinion leadership and product involvement, among other variables (Reynolds and Darden 1971; Summers 1970). Despite the rather wobbly theoretical and empirical underpinnings for the conclusion, however, involvement seems to be accepted as the motive for opinion leadership. Feick and Price (1987) summarize current thinking as follows:

The implicit assumption in examining the personal influence of opinion leaders is that they are motivated to talk about the product because of their involvement with it…. Product involvement remains the predominant explanation for opinion leaders’ conversations about products.

The essential behavior said to define opinion leaders is that they talk about products, yet the linkage between opinion leadership, as commonly measured, and actual word-of-mouth is not well understood. Only a few studies have measured word-of-mouth separately from opinion leadership, and even these studies have used global measures of WOM such as asking “how much” respondents talk with others about a product category (e.g., Myers and Robertson 1972). Little if any research has examined the content of opinion leaders’ comments or attempted to distinguish the conversational content of opinion leaders vis a vis consumers who are not opinion leaders.

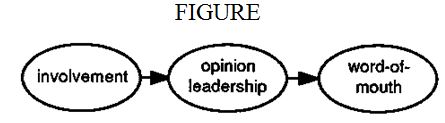

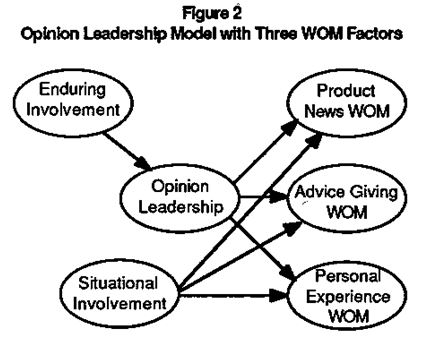

Thus, while empirical evidence is not especially voluminous, the model of opinion leadership implied by consumer behavior writers can be represented as follows:

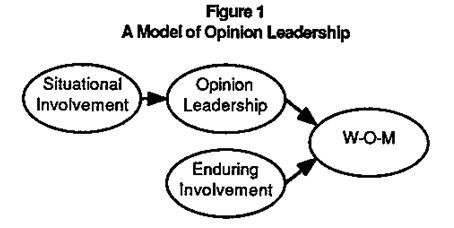

There are, however, some inadequacies with the implicit model of opinion leadership, primarily with respect to the involvement variable. Dichter (1966, p. 148), in his explanation of how product involvement results in word-of-mouth, suggested that “experience with the product (or service) produces a tension which is not eased by the use of the product alone, but must be channeled by way of talk, recommendation, and enthusiasm….” While any form of product excitement may result in WOM, it is questionable that all types of product “excitement” or involvement result in opinion leadership. – Recent distinctions in the product involvement literature (Bloch and Richins 1983; Houston and Rothschild 1978) suggest that product involvement may be transitory (situational) or it may be long term and enduring. Because of the transitory nature of situational involvement, it is unlikely to result in a relatively permanent state such as opinion leadership. For this reason, the implicit model of opinion leadership is altered for purposes of this research. As shown in Figure 1, enduring involvement is expected to result in opinion leadership, which in turn results in word-of-mouth. Situational involvement is expected to result in word-of-mouth but to have no linkage with opinion leadership.

A MODEL OF OPINION LEADERSHIP-

The research reported here tests this revised model of opinion leadership. It also explicitly tests the link between opinion leadership and word-of-mouth, and does so with specific rather than global WOM measures used in earlier research.

METHODOLOGY

Product Class-

Automobiles were chosen as a suitable product class for this study for several reasons. First, it was desirable to use a product owned by a large percentage of the general population. Second, to assess situational involvement effects it was necessary to choose a product capable of eliciting high levels of situational involvement, at least al the point of purchase; prior research has shown this to be the case for automobiles (Hupfer and Gardner 1971; Richins and Bloch 1986). Access to a list of new car registrants permitted the identification of respondents who can be said to possess high situational involvement at the time of the survey. Finally, a product capable of eliciting high levels of enduring involvement among some but not all consumers was needed to provide an adequate range on the enduring involvement construct (Bloch 1981).

Data Collection:

Data were collected using a mail survey with follow-up reminder. Questionnaires were mailed to a randomly drawn sample of 650 adult consumers living in a medium sized Sunbelt city; 217 of these returned usable forms. To provide responses along the complete range of the situational involvement construct, this general population sample was supplemented with a mailing to 125 new car owners identified from state motor vehicle registration office records. 53 usable forms were obtained from this sample, yielding a total sample size of 270. While the inclusion of the supplemental sample limits the external validity of the study, it should be noted that it is not the intention of this study to make specific generalizations from a sample to a population of interest but rather to understand underlying theoretical processes.

Measures:

Opinion leadership was measured using four items taken from the King and Summers (1970) scale. A five point response format was used (Childers 1986) instead of the usual dichotomous response format. The items were summed to form a composite measure of opinion leadership. Cronbach’s alpha equalled .82, indicating that the reliability of the scale was not compromised by using a shortened version.

Enduring involvement was measured using the 9-item version of the automobile involvement scale developed by Bloch (1981; see Richins and Bloch 1986). The summed scale had an alpha of .90.

The recent purchase of a new car was used as a dummy variable indicator of situational involvement. The short term temporal nature of situational involvement has been discussed in the literature (Antil 1984; Bloch and Richins 1983; Houston and Rothschild 1978). Following Richins and Bloch (1986), a two-month period was used to divide respondents into high and low situational involvement groups; those respondents who had purchased a new automobile within the two months prior to the study were placed in the high situational involvement category.

Types of word-of-mouth were measured using 13 items generated from depth interviews of adult consumers who described product-related conversations in which they had recently participated. Questionnaire items were designed to measure frequency of different types of comments about automobiles. Respondents indicated the number of times they had discussed each topic within the last two weeks. Pretesting had revealed that respondents have some difficulty in recalling the precise number of comments made over a two-week period. However, respondents were generally confident that the ordinal relationship among the types of comments was correct. In other words, they believed their estimates accurately reflected which types of comments they made more frequently and less frequently than others.

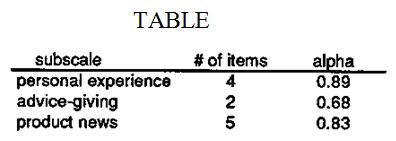

Principal components analysis with oblique rotation resulted in four factors for word-of-mouth comments, which were labeled positive personal experience, advice-giving, product news, and negative word-of-mouth. Because of concern for the level of measurement, this analysis was performed twice, once using a matrix of Pearson r’s and the second time a matrix of rank correlations. Results did not differ.

Positive personal experience word-of-mouth consists of comments in which respondents made favorable statements about their cars or described how or why they bought their cars. All these topics are related to respondents’ personal experiences. Advice-giving word-of-mouth included comments in which respondents gave information about cars or advice about which car to buy This factor seems to capture the dimension of word-of-mouth communication which has traditionally been studied in the opinion leadership literature (Jacoby 1974; Rogers and Cartano 1962). Product news includes comments about advances in car technology, car model differences, and similar topics. In contrast to the first word-of-mouth dimension, comments loading highly on this factor seem to be based less on personal experience with one’s own car and more on general knowledge about automobiles as a product class.

Negative word-of-mouth consists of statements in which respondents said something unfavorable about their cars or described something they didn’t like about them. Preliminary analysis showed that this type of word-of-mouth had no significant relationship with either involvement or opinion leadership, so only the first three word-of-mouth factors were used for the remainder of the study.

Items in each of the three remaining factors with loadings greater than .6 on the pattern matrix were summed to create the three word-of-mouth subscales, as follows:

Because the distributions of the word-of-mouth variables were highly skewed, square root transformations for these variables were used in subsequent analyses. The three word-of-mouth factors require a slightly more complex model, shown in Figure 2.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS:

The path coefficients for the recursive model were estimated by ordinary least squares regression using path analysis techniques arising from the work of Simon and

FIGURE 2

OPINION LEADERSHIP MODEL WITH THREE WOM FACTORS

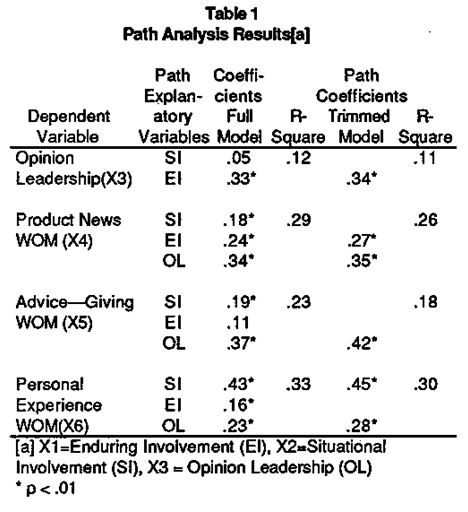

Blalock (see Asher 1983; Blalock 1964; Pedhazer 1982). In order to test whether the path coefficients assumed to be zero in the hypothesized model were indeed zero, -these linkages were included in the initial test of the model. Regression results are shown in Table 1.

In interpreting regression results, statistical significance was not the only criterion used to determine whether a path should be included in the model. Because of the large sample size, even coefficients of small magnitude may achieve statistical significance. Therefore, an arbitrary cutoff was used in addition to the significance criterion. Path coefficients less than .20 (accounting for less than 4% of variance) were considered marginal and corresponding linkages omitted from the final model.

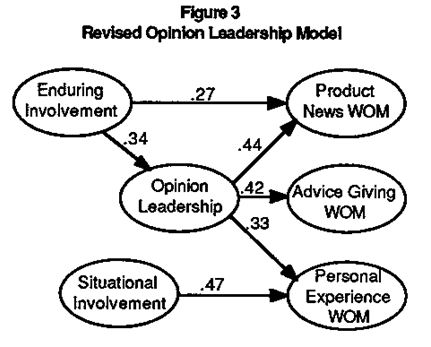

Regression results indicate that the hypothesized model needs to be modified. Two hypothesized linkages were not strong enough to be maintained. The path coefficients for hypothesized links between situational involvement and two forms of word-of-mouth (product news and advice-giving) were less than .20; these links were eliminated. Regression analysis also revealed that an additional path needs to be added to the model. The coefficient for the path between enduring involvement and product news word-of-mouth was .24 (pc.01); a path connecting these two variables was added. The revised model reflecting these changes is shown in Figure 3.

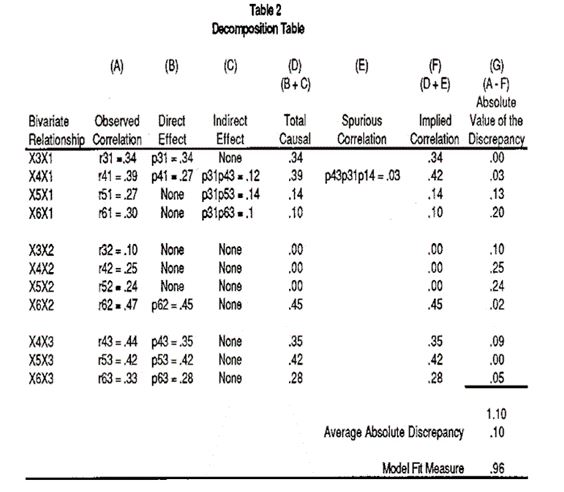

The revised model was evaluated in terms of how well correlations derived from the model reproduce actual correlations among variables. Small discrepancies between derived and actual correlations are indicative of good fit. Table 2 shows the decomposition table for the final model. Model fit appears to be adequate, with an average discrepancy between derived and observed correlations of .10. In addition, the model fit measure recommended by Duffy et al. (1981, p. 479) was calculated and equalled .96, indicating that the model has an average of 4 percent error in predicting covariance of pairs of variables.

DISCUSSION-

The results of these analyses provide partial support for the involvement-> opinion leadership-> word-of-mouth model implied in the literature. Involvement does appear to be an important antecedent to opinion leadership, but it is necessary to specify that only enduring involvement results in opinion leadership. Situational involvement bears no relationship at all with opinion leadership. Likewise, the implicit relationship between opinion leadership and word-of-mouth is confirmed. It is not surprising that the relationship between opinion leadership and word-of-mouth is strongest for advice-giving, the form of word-of-mouth traditionally linked with opinion leadership. In these respects, the implicit model is correct.

Findings also indicate that the implicit model inadequately represents word-of-mouth communication. Word-of-mouth results from situational involvement not just from opinion leadership. Situational involvement is especially associated with personal experience word-of-mouth. For at least a brief period, consumers seem to engage in product-related conversations after the purchase of new automobile because of the excitement generated by the new item (Dichter 1966) or possible cognitive dissonance (Menasco and Hawkins 1978). This arousal dissipates over the course of time, however, and product-related word-of-mouth declines as well.

Although the hypothesized model shown in Figure 2 is better than the implicit model in representing antecedents of word-of-mouth communications, it too is deficient. Counter to the hypothesized model, results indicate that the relationship between situational involvement and word-of-mouth other than personal experience word-of-mouth is weak. Subsequent to a new car purchase, consumers increase their talk about their own cars and how they shopped for them. Their discussions of other car-related topics such as product news and advice-giving also seem to increase, but only a little, as evinced by the small coefficients for the proposed paths between situational involvement and these forms of word-of-mouth. However, these coefficients did approach the cutoff point for inclusion in the model. Further research using other product classes is needed to determine more conclusively whether these paths should be deleted or retained.

Also counter to the hypothesized model, results indicate that enduring involvement is directly related to product-news word-of-mouth. The relationship between enduring involvement and word-of-mouth operates through opinion leadership for all three word-of-mouth content factors. However, for product news word-of-mouth, enduring involvement has a direct relationship with word-of-mouth in addition to its indirect effects through opinion leadership. As a result of interest and excitement in a product category, the product enthusiast is eager to discuss recent developments in a product category, beyond the opinion leadership role.

These product news discussions apparently contain elements not related to opinion leadership, and the existence of this direct link may be due in part to the nature of the traditional opinion leadership measure used in marketing studies. For example, the most commonly used opinion leadership scale (King and Summers 1970) has items that ask respondents whether they “tell others” about the product class or if “others tell them” about the product class, with the former response indicative of high opinion leadership. -Research has shown, however, that opinion leaders tend to ask for as well as give information (Reynolds and Darden 1971). Consumers highly involved in a product such as cars engage in (often fervent) conversations with others of like mind. These tend to be mutual, two-way conversations with each highly involved participant giving information to the other, receiving information, and comparing opinions. A highly involved consumer who frequently engages in such conversations, then, would answer at the midpoint of the scale, lowering his or her opinion leadership score. This suggests that such items on the long-accepted opinion leadership scales commonly used in marketing should be eliminated or revised when studying consumers who may be very high in enduring involvement and/or opinion leadership.

In sum, this study of opinion leadership for automobiles has shown that (1) enduring involvement appears to give rise to opinion leadership, (2) enduring involvement has links with some forms of word-of-mouth outside the opinion leadership construct, as normally measured in marketing, (3) situational involvement is not related to opinion leadership, (4) situational involvement has its strongest influence on word-of-mouth about one’s own experiences, and (5) opinion leadership is most strongly associated with word-of-mouth comments that include information and advice-giving. Further research can determine the generalizability of these findings to other product classes. Additional work refining the most frequently used opinion leadership scale items and assessing their validity at the extreme end of the construct is also warranted.