A woman’s immune system undergoes significant alterations during pregnancy, but researchers do not yet fully grasp all of the underlying mechanisms. A recent study reveals how the gut flora could play a role. In a publication published this week in mSystems, Chinese researchers suggest that changes in cytokines — immune system proteins involved in inflammation — during pregnancy may be connected to particular changes in the mother’s gut microbiome as well as plasma and feces.

“To the best of our knowledge, these associations were first explored in our study,” stated first author Ting Huang, M.D., of Jinan University’s First Affiliated Hospital in Guangzhou, China.

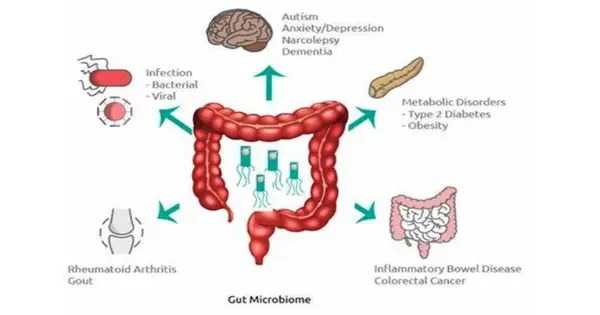

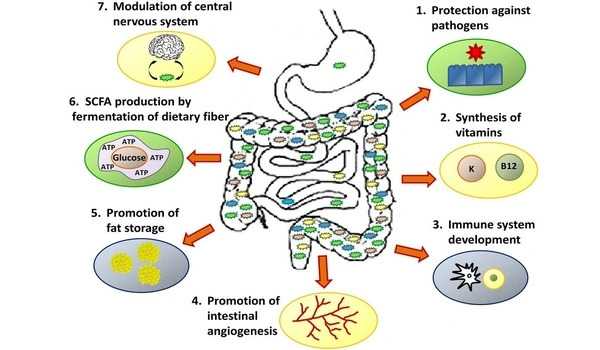

Pregnancy causes a slew of changes, including hormonal shifts, alterations to a woman’s bodily structure, and immune system modifications. Previous research has discovered alterations to the gut microbiota that might occur during pregnancy; these changes may also influence physiological processes in the mother via metabolites. Disruptions in the microbiota, for example, have been linked to the development of preeclampsia, a serious pregnancy disorder marked by elevated blood pressure. However, it is unknown how changes in the gut microbiome during pregnancy influence maternal immunity.

Analyses of the fecal samples showed that Firmicutes was the most dominant phylum of bacteria in both groups of women. However, Bacteroidota bacteria accounted for a smaller relative share of the microbial population in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women. Pregnant women also showed a higher relative abundance of both Actinobacteriota and Proteobacteria, compared to non-pregnant women.

To investigate these connections, the researchers at the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University compared the gut microbiota, metabolite profiles and immune system status of 30 healthy pregnant women to 15 healthy women who weren’t pregnant. All the women in the study were between 18 and 34 years old. Fecal and blood samples were collected from the pregnant women during or after the 37th week of pregnancy, and samples from non-pregnant women were collected on the 14th day of the menstrual cycle.

Analyses of the fecal samples showed that Firmicutes was the most dominant phylum of bacteria in both groups of women. However, Bacteroidota bacteria accounted for a smaller relative share of the microbial population in pregnant women than in non-pregnant women. Pregnant women also showed a higher relative abundance of both Actinobacteriota and Proteobacteria, compared to non-pregnant women.

The researchers similarly found a distinct difference in the cytokine levels in the 2 groups. Pregnant women had lower levels of cytokines that promote inflammation, and they showed higher levels of cytokines that act against inflammation. These results suggest that the immune system may be suppressed during pregnancy, the authors noted.

The researchers then identified hundreds of metabolites found in the plasma and fecal samples. They found that each group — pregnant and non-pregnant women — had its own distinct collection of metabolites, or metabolome. Notably, many of those metabolites were connected to bile acid secretion and metabolism, and bile acids have previously been tied to inflammation. In further analyses, they found that some enriched metabolites in pregnant women were associated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Similarly, some of the depleted metabolites are associated with increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Finally, the researchers found 46 relationships between microorganisms, metabolites, and cytokines. They discovered that some bacteria concentrated in pregnant people, for example, can suppress an immune response by suppressing pro-inflammatory chemicals. Overall, Huang stated that the findings support the hypothesis that gut bacteria interact with host metabolites to alter cytokine levels in the blood.

However, Huang stated that the findings did not show causation. Furthermore, the small sample size may increase mistakes due to individual differences, and the study’s design does not account for potential confounding factors such as food. More clinical trials, the researchers noted, are required to validate and better understand the linkages.