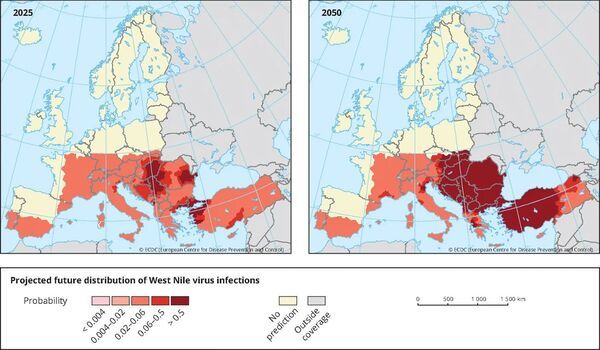

Researchers explain how climate change contributes to the spatial spread of West Nile virus in Europe, a pathogen that poses a new public health concern to the continent. Their findings show that the area environmentally favorable for virus circulation has increased significantly since the turn of the century, as has the human population’s risk of exposure, owing in part to climate change.

In a study published this week in the journal Nature Communications, researchers from the Spatial Epidemiology Lab at the University of Brussels (ULB) and their collaborators show how climate change contributes to the spatial spread of West Nile virus in Europe, a virus that poses a new public health threat to the continent. Their findings show that the area environmentally favorable for virus circulation has increased significantly since the turn of the century, as has the human population’s risk of exposure, owing in part to climate change.

West Nile virus is an emerging disease in Europe, posing a public health risk in previously unaffected European countries. This virus, which occurs in a cycle involving transmission between bird and mosquito species, can be transmitted to humans by mosquitos and cause West Nile disease. While most human infections are asymptomatic, approximately 25% of patients have symptoms such as fever and headache, with less than 1% developing more serious neurological problems that can lead to death.

Our results point towards a significant responsibility of climate change in the establishment of West Nile virus in the south-eastern part of the continent. In particular, we identify that current West Nile virus hotspots in Europe are most likely to be attributed to climate change.

Diana Erazo

While climate change has been cited as a potential driver of the emergence of West Nile virus on the European continent, a formal evaluation of this causal relationship was lacking. In a study published in the journal Nature Communications, researchers from the University of Brussels (ULB) — Diana Erazo and Simon Dellicour from the Spatial Epidemiology Laboratory — and their collaborators investigated the extent to which West Nile virus spatial expansion in Europe can be attributed to climate change while accounting for other direct human influences such as land use and human population changes.

To this end, they adopted a machine learning approach to predict the risk of local West Nile virus circulation given local environmental conditions. They subsequently unravelled the isolated effect of climate change by comparing factual simulations to a counterfactual where climate change had been removed.

“Our results point towards a significant responsibility of climate change in the establishment of West Nile virus in the south-eastern part of the continent. In particular, we identify that current West Nile virus hotspots in Europe are most likely to be attributed to climate change” explains Diana Erazo, first author of the study and post-doctoral researcher at the Spatial Epidemiology Lab.

“Our results also demonstrate a recent and drastic increase of the population at risk of exposure. While this increase is partly due to an increase in population density, we show that climate change has also been a critical factor driving the risk of West Nile virus exposure in Europe.”

The study was made feasible by the collaboration of scholars with diverse backgrounds, and it is also the product of an interdisciplinary approach. “Our work demonstrates how climate data can be effectively used in an epidemiological context by estimating the virus’s past and present ecological suitability, closing another analytical gap between climate science and epidemiology,” says Simon Dellicour, the study’s supervisor and head of the Spatial Epidemiology Lab.

“With climate change emerging as a critical public health challenge, future work should explore the evolution of infectious disease distributions under different scenarios of future climate change to inform surveillance and intervention strategies.”