Prion Diseases

Prion Diseases comprise several conditions. A prion is a type of protein that can trigger normal proteins in the brain to fold abnormally. Prion diseases can affect both humans and animals and are sometimes spread to humans by infected meat products. The most common form of prion disease that affects humans is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD).

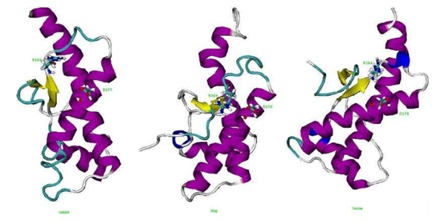

Even though prion diseases do come in slightly different forms, they have a whole lot in common. In each disease, the prion protein (PrP) folds up the wrong way, becoming a prion, and then causes other PrP molecules to do the same. Prions can then spread “silently” across a person’s brain for years without causing any symptoms. Eventually prions start to kill neurons, and once symptoms strike, the person has a very rapid cognitive decline. Most prion diseases are fatal within a few months, though some can last a few years.

Prion diseases in humans are fairly rare – about 1 in 1 million people dies of a prion disease each year. Prion diseases can come about in one of three ways: acquired, genetic or sporadic.

Prion diseases can also be genetic. First, let’s recall some biology basics. DNA contains instructions which get re-written in RNA, and then the instructions in RNA get translated into protein. So changes in a person’s DNA can cause changes in the proteins their cells produce. Everyone has a gene called PRNP which codes for the protein called PrP, and most of the time this protein is perfectly healthy and fine. Some people have mutations in the DNA of their PRNP gene, which cause it to produce mutant forms of PrP. These mutant forms don’t form prions instantly, and most people with PRNP mutations live perfectly healthy for decades. But as people get older, the mutant forms of PrP are more and more likely to fold up the wrong way and form prions. Once they do, the person has a rapid neurodegenerative disease.

Causes of Prion Disease

Prion diseases occur when normal prion protein, found on the surface of many cells, becomes abnormal and clump in the brain, causing brain damage. This abnormal accumulation of protein in the brain can cause memory impairment, personality changes, and difficulties with movement. Experts still don’t know a lot about prion diseases, but unfortunately, these disorders are generally fatal.

Symptoms of Prion Diseases

Symptoms of prion diseases include:

- Rapidly developing dementia

- Difficulty walking and changes in gait

- Hallucinations

- Muscle stiffness

- Confusion

- Fatigue

- Difficulty speaking

Kuru

In the 1950s-1960s, kuru reached epidemic proportions in the South Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea. Although researchers do not know how it started, they know it spread when tribal members ritualistically consumed the tissue of affected people during funeral rites. Kuru is characterized by walking problems, shaking of the limbs, slurred speech and mood changes, but little or no dementia. It is usually fatal within 6 to 12 months. Kuru disappeared with the end of cannibalistic practices in New Guinea.

Treatments for Prion Disease

Prion diseases are different from most other types of diseases. Prions can act like an infection as they travel from cell to cell in a person’s body, yet unlike viruses or bacteria, they have no DNA or RNA – they’re just made of protein. There has never before been a treatment for a disease like this, so right now it isn’t yet clear which strategy will ultimately lead to a treatment or cure. Scientists are investigating a lot of different possible ways of treating these diseases.

As far as we know, sporadic and genetic prion diseases in humans start in the brain, so there’s no opportunity to treat them in the periphery. From what we know right now, a clinical trial, if one happens, would most likely involve intravenous injections of antibodies in patients who are already experiencing symptoms. This approach hasn’t worked in mice, presumably because not much of the antibody got into the brain. The folks at MRC Prion Unit have pointed to evidence that the blood-brain barrier may be broken down in prion disease patients, which would help the antibodies to get across, and as noted here they’ve also raised the possibility of eventually administering antibodies directly into the brain instead of into the bloodstream. In animal studies, direct injections of antibodies into the brain have been shown to have some small effect (survival was extended by ~8%) though the animals were not cured.

Another proposed strategy is stem cell therapy for prion disease. This has been proposed in various forms: it could involve trying to generate new brain cells to replace ones that patients have lost, or it could involve adding extra, genetically modified cells to a patient’s brain to produce special proteins or other therapeutic agents that will slow down prion infection. Our view is that any sort of stem cell therapy is probably quite a long way from being useful to prion disease patients. That’s not to say it couldn’t happen someday – it is an active area of research for Parkinson’s disease, for instance, and we’ll see what new technologies are developed.

Prion Disease and Infection Control

Prion disease is not contagious; there is no evidence to suggest it can be spread from person to person by close contact. Once a person has developed prion disease, central nervous system tissues (brain, spinal cord and eye tissue) are thought to be extremely infectious. However this is only relevant for those handling infected tissue directly, which does not include carers looking after a person with the disease.

Infectivity in the rest of the body varies in different types of prion disease but is generally much less than in brain tissue. People with any form of prion disease are requested not to be blood or organ donors, and are requested to inform their doctor and dentist prior to any invasive medical procedures or dentistry.

As prions cannot be completely destroyed by conventional sterilisation procedures, transmission has also occurred inadvertently through the use of surgical instruments previously used during neurosurgery on a person with sporadic prion disease. Current Department of Health guidelines are that all surgical instruments used on medium or high infectivity tissues in a patient with suspected prion disease are quarantined and not re-used unless an alternative diagnosis is confirmed. Instruments used on patients with known prion disease are not reused.