Biography of Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland – American composer, composition teacher, writer, and a conductor.

Name: Aaron Copland

Date of Birth: November 14, 1900

Place of Birth: Brooklyn, New York, United States

Date of Death: December 2, 1990 (aged 90)

Place of Death: Sleepy Hollow, New York, United States

Occupation: Composer, Conductor, Writer, and Teacher

Father: Harris Morris Copland

Mother: Sarah Mittenthal Copland

Early Life

An American composer who achieved a distinctive musical characterization of American themes in an expressive modern style, Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as “the Dean of American Composers”. The open, slowly changing harmonies in much of his music are typical of what many people consider to be the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. Both as a composer (a writer of music) and as a spokesman who was concerned about making Americans aware of the importance of music. He won the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1945.

Copland innovatively blended popular forms of American music such as jazz and folk into his compositions to create exceptional pieces. Copland had contributed a lot to the music industry both as a composer and as a speaker, who made the Americans aware of the importance of music. Through his compositions, polemics, promotions, and plain hard work, Copland established American concert music. He had a distinctly American style of composition and was often referred to as the “Dean of American Composers”. Incorporating elements of jazz and serial techniques, Copland wrote ballets, orchestral music, chamber music, vocal works, operas, and film scores. This talented musician was a boon to the American music industry as he traveled to elevate the status of American music abroad. His commitment to music and the country made him one of the most prominent and remembered composers not only a good but also a great composer indeed.

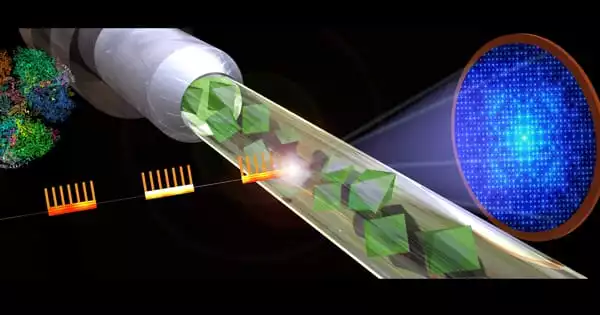

During the late 1940s, Copland became aware that Stravinsky and other fellow composers had begun to study Arnold Schoenberg’s use of twelve-tone (serial) techniques. After he had been exposed to the works of French composer Pierre Boulez, he incorporated serial techniques into his Piano Quartet (1950), Piano Fantasy (1957), Connotations for orchestra (1961) and Inscape for orchestra (1967). Unlike Schoenberg, Copland used his tone rows in much the same fashion as his tonal material as sources for melodies and harmonies, rather than as complete statements in their own right, except for crucial events from a structural point of view. From the 1960s onward, Copland’s activities turned more from composing to conducting. He became a frequent guest conductor of orchestras in the U.S. and the UK and made a series of recordings of his music, primarily for Columbia Records.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Aaron Copland was born to a conservative Jewish family of Lithuanian origin on 14 November 1900, in Brooklyn, New York. His parents were Harris Morris Copland and Sarah Mittenthal Copland. Among their five children, Aaron was the youngest one. Their original family name was ‘Kaplan.’ His father had changed it earlier due to certain reasons, though Aaron himself was unaware of the fact for a long time.

Throughout his childhood, Copland and his family lived above his parents’ Brooklyn shop, H.M. Copland’s, at 628 Washington Avenue (which Aaron would later describe as “a kind of neighborhood Macy’s”), on the corner of Dean Street and Washington Avenue, and most of the children helped out in the store. His father was a staunch Democrat. The family members were active in Congregation Baith Israel Anshei Emes, where Aaron celebrated his Bar Mitzvah. Not especially athletic, the sensitive young man became an avid reader and often read Horatio Alger stories on his front steps.

Unlike his father who was not interested in music at all, his mother liked to sing as well as play the piano, and she arranged musical classes for the children too. Among Copland’s siblings, his older brother Ralph was the most talented in music, having become proficient with the violin at a very young age. It was Aaron’s sister Laurine, who was the closest to him among all his siblings. She supported and encouraged him in his career. At the early age of eight, Copland started writing songs, and at the age of eleven, he composed his first notated music for an opera scenario. Later, he studied under Leopold Wolfsohn for a period of four years.

At age fifteen Copland decided he wanted to be a composer. While attending Boys’ High School he began to study music theory beginning in 1917. Goldmark, with whom Copland studied between 1917 and 1921, gave the young Copland a solid foundation, especially in the Germanic tradition. As Copland stated later: “This was a stroke of luck for me. I was spared the floundering that so many musicians have suffered through incompetent teaching.” But Copland also commented that the maestro had “little sympathy for the advanced musical idioms of the day” and his “approved” composers ended with Richard Strauss.

Copland continued his music lessons after graduating from high school, and in 1921 he went to France to study at the American Conservatory in Fontainebleau, where his main teacher was the French composer Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). During his early studies, Copland had been attracted to the music of Scriabin (1872-1915), Debussy (1862-1918), and Ravel (1875-1937). The years in Paris provided him an opportunity to hear and absorb all the most recent trends in European music, including the works of Stravinsky (1882-1971), Bartók (1881-1945), and Schoenberg (1847-1951).

Personal Life

Aaron Copland never enrolled as a member of any political party. Nevertheless, he inherited a considerable interest in civic and world events from his father. His views were generally progressive and he had strong ties with numerous colleagues and friends in the Popular Front, including Odets. Early in his life, Copland developed, in Pollack’s words, “a deep admiration for the works of Frank Norris, Theodore Dreiser and Upton Sinclair, all socialists whose novels passionately excoriated capitalism’s physical and emotional toll on the average man”. Even after the McCarthy hearings, he remained a committed opponent of militarism and the Cold War, which he regarded as having been instigated by the United States. He condemned it as “almost worse for art than the real thing”. Throw the artist “into a mood of suspicion, ill-will, and dread that typifies the cold war attitude and he’ll create nothing”.

Copland never married and remained a bachelor throughout his life. It is believed that he was gay and had love affairs with several men including Victor Kraft, artist Alvin Ross, pianist Paul Moor, and dancer Erik Johns.

Career and Works

In the summer of 1921, Aaron Copland attended the newly founded school for Americans at Fontainebleau, where he came under the influence of Nadia Boulanger, a brilliant teacher who shaped the outlook of an entire generation of American musicians. He decided to stay on in Paris, where he became Boulanger’s first American student in composition. After three years in Paris, Copland returned to New York City with an important commission: Nadia Boulanger had asked him to write an organ concerto for her American appearances. Copland composed the piece while working as the pianist of a hotel trio at a summer resort in Pennsylvania. That season the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra had its premiere in Carnegie Hall with the New York Symphony under the direction of the composer and conductor Walter Damrosch.

After Copland completed his studies in 1924, he returned to America and composed the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra, his first major work, which Boulanger played in New York City in 1925. Music for the Theater (1925) and a Piano Concerto (1926) explored the possibilities of combining jazz and symphony music. Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951), a conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, became interested in what he heard from the young composer, and he helped gain a wider audience for Copland’s and much of America’s music.

Later on, Copland was drawn to jazz and popular music, genres which he had explored previously as well while he was in Europe. Several of his works, including ‘Four Piano Blues’ had a Jazz influence. In the late 1920s, Copland turned to an increasingly experimental style, featuring irregular rhythms and often jarring sounds.

Copland’s compositions in the early 1920s reflected the modernist attitude that prevailed among intellectuals, that the arts need be accessible to only a cadre of the enlightened and that the masses would come to appreciate their efforts over time. However, mounting troubles with the Symphonic Ode (1929) and Short Symphony (1933) caused him to rethink this approach. It was financially contradictory, particularly in the Depression. Avant-garde music had lost what cultural historian Morris Dickstein calls “its buoyant experimental edge” and the national mood toward it had changed.

As an author, Aaron Copland wrote the first edition of ‘What to Listen for in Music.’ In the book, which was published in 1939, he gives the reader proper guidance on the appreciation of music. He also wrote and published ‘Our New Music’ and ‘Music and Imagination’ in 1941 and 1952 respectively. Copland spent his time in other countries during the Great Depression years. He went to Europe, Africa, and then to Mexico as well, where he got acquainted with the Mexican composer Carlos Chavez. He composed several musical works using Mexican folk music as well, such as ‘El Salon Mexico.’

From 1927 to 1930 and 1935 to 1938, Copland taught classes at The New School of Social Research in New York City. Eventually, his New School lectures would appear in the form of two books What to Listen for in Music (1937, revised 1957) and Our New Music (1940, revised 1968 and retitled The New Music: 1900-1960). During this period, Copland also wrote regularly for The New York Times, The Musical Quarterly and a number of other journals. These articles would appear in 1969 as the book Copland on Music.

The 1920s and 1930s were a period of deep concern about the limited audience for new (and especially American) music, and Copland was active in many organizations devoted to performance and sponsorship. These included the League of Composers, the Copland-Sessions concerts, and the American Composers’ Alliance. His organizational abilities earned him the title of “American music’s natural president” from his fellow composer Virgil Thomson (1896-1989).

The decade that followed saw the production of the scores that spread Copland’s fame throughout the world. Most important of these were the three ballets based on American folk material: Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944; commissioned by dancer Martha Graham). To this group belong also El salón México (1936), an orchestral piece based on Mexican melodies and rhythms; two works for high-school students the “play opera” The Second Hurricane (1937) and An Outdoor Overture (1938); and a series of film scores, of which the best known are Of Mice and Men (1939), Our Town (1940), The Red Pony (1948), and The Heiress (1948). Typical too of the Copland style are two major works that were written in the time of war Lincoln Portrait (1942), for speaker and chorus, on a text drawn from Lincoln’s speeches, and Letter from Home (1944), as well as the melodious Third Symphony (1946).

The Clarinet Concerto (1948), scored for solo clarinet, strings, harp, and piano, was a commission piece for bandleader and clarinetist Benny Goodman and a complement to Copland’s earlier jazz-influenced work, the Piano Concerto (1926). His Four Piano Blues is an introspective composition with a jazz influence. Copland finished the 1940s with two film scores, one for William Wyler’s The Heiress and one for the film adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel The Red Pony. In 1949, Copland returned to Europe, where he found French composer Pierre Boulez dominating the group of post-war avant-garde composers there. He also met with proponents of twelve-tone technique, based on the works of Arnold Schoenberg, and found himself interested in adapting serial methods to his own musical voice. Copland also worked on ‘The Heiress’ in 1949 for which he was awarded an Oscar.

Aaron Copland’s concern for establishing a tradition of music in American life increased when he became a teacher at The New School for Social Research at Harvard University, and as head of the composition department at the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood, Massachusetts, a school founded by Koussevitzky. His Norton Lectures at Harvard (1951-52) were published as Music and Imagination (1952). Earlier books are What to Listen for in Music (1939) and Our New Music (1941). Beginning with the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), Copland made use of the methods developed by Austrian American composer Arnold Schoenberg, who developed a tonal system not based on any key. This confused many listeners. Copland’s most important works of these years include the Piano Fantasy (1957), Nonet for Strings (1960), Connotations (1962), and Inscape (1967). The Tender Land (1954) represents an extension of the style of ballet to the opera stage.

In 1950, Aaron Copland received a U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission scholarship to study in Rome, which he did the following year. Around this time, he also composed his Piano Quartet, adopting Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method of composition, and Old American Songs (1950), the first set of which was premiered by Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten, the second by William Warfield. During the 1951-52 academic year, Copland gave a series of lectures under the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship at Harvard University. These lectures were published as the book Music and Imagination.

His later works included the use of the twelve-tone system of Aaron Schonberg, though he didn’t fully embrace it. Copland was also inspired by the French composer Pierre Boulex, who showed him various other ways to use this technique. Copland often used twelve-tone techniques in the later part of his career. But he went back and forth in using it instead of sticking it to it exclusively, as it was not well received by most people. Among such works are ‘Piano Fantasy’ (1957) and ‘Connotations’ (1962); which was commissioned for the opening of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York City; and Inscape (1967). The 12-tone works were not generally well-received; after 1970 Copland virtually stopped composing, though he continued to lecture and to conduct through the mid-1980s.

In 1957, 1958, and 1976, Aaron Copland was the Music Director of the Ojai Music Festival, a classical and contemporary music festival in Ojai, California. For the occasion of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, Copland composed Ceremonial Fanfare For Brass Ensemble to accompany the exhibition “Masterpieces Of Fifty Centuries”. Leonard Bernstein, Walter Piston, William Schuman, and Virgil Thomson also composed pieces for the Museum’s Centennial exhibitions. From 1960 to his death, Copland resided at Cortlandt Manor, New York. Known as Rock Hill, his home was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003 and further designated a National Historic Landmark in 2008.

During his career, Aaron Copland also assisted hundreds of young composers who admired his talent in music. However, the young musicians he taught were his students only for brief periods. Copland advised his students to focus on expression rather than on technical points. He also encouraged them to have their own personal style. From around 1970, he decided to stop composing and focus more on teaching instead.

Aaron Copland spent the final years of his life living primarily in the New York City area. He engaged in many cultural missions, especially to South America. Although he had been out of the major spotlight for almost twenty years, he remained semiactive in the music world up until his death, conducting his last symphony in 1983.

Awards and Honor

For his music in the film ‘The Heiress’ (1949), Aaron Copland was awarded the Academy Award for Original Music Score.

In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Aaron Copland was awarded the prestigious ‘University of Pennsylvania Glee Club’ award in 1970 because of the immense influence he had on American music. Copland was also awarded Yale University’s, Sanford Medal.

Copland was the honorary member of the Alpha Epsilon chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia in 1961 and was awarded the fraternity’s Charles E. Lutton Man of Music Award in 1970.

Copland was honored with the National Medal of Arts in 1986. The United States Congress awarded Copland with a special Congressional Gold Medal in 1987.

Death and Legacy

Aaron Copland’s health deteriorated through the 1980s, and he died of Alzheimer’s disease and respiratory failure on December 2, 1990, in North Tarrytown, New York (now Sleepy Hollow) and his ashes were scattered over the Tanglewood Music Center near Lenox, Massachusetts. Much of his large estate was bequeathed to the creation of the Aaron Copland Fund for Composers, which bestows over $600,000 per year to performing groups.

One of his most popular works was ‘Rodeo’ which was premiered in 1942. It was a ballet consisting of five sections: ‘Buckaroo Holiday’, ‘Corral Nocturne’, ‘Ranch House Party’, ‘Saturday Night Waltz’, and ‘Hoe-Down.’ Considered as one of the earliest examples of a truly American ballet, ‘Rodeo’ can be regarded as the combination of Broadway music with classical ballet. ‘Symphony No. 3’ which was Aaron Copland’s third and final symphony, is among one of his significant works. It was premiered on October 19, 1946, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzy. It was written at the end of the Second World War, and it is regarded as the essential American symphony as it fuses Copland’s distinct ‘Americana’ style with the form of the symphony. ‘The Tender Land’ an opera with music was another one of Aaron Copland’s works. The work was premiered at the New York City Opera on 1 April 1954. It was initially poorly received, due to which Copland decided to make revisions.

For the better part of four decades, as composer (of operas, ballets, orchestral music, band music, chamber music, choral music, and film scores), teacher, writer of books and articles on music, organizer of musical events, and a much sought after conductor, Copland expressed “the deepest reactions of the American consciousness to the American scene.” He received more than 30 honorary degrees and many additional awards. His books include What to Listen for in Music (1939), Music and Imagination (1952), Copland on Music (1960), and The New Music, 1900-60 (1968). With the aid of Vivian Perlis, he wrote a two-volume autobiography (Copland: 1900 Through 1942 (1984) and Copland: Since 1943 (1989)). He was remembered as a man who encouraged young composers to find their own voice, no matter the style, just as he had done for sixty years.

Information Source: