Biography of Andre Marie Ampere

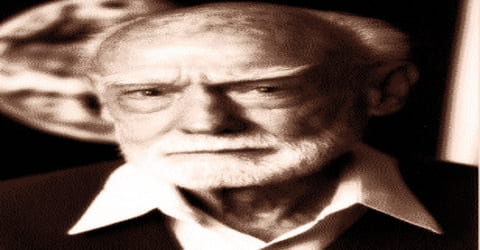

Andre Marie Ampere – French physicist and mathematician.

Name: Andre Marie Ampere

Date of Birth: 20 January 1775

Place of Birth: Lyon, France

Date of Death: 10 June 1836 (aged 61)

Place of Death: Marseille, France

Occupation: Mathematician, Physicist

Father: Jean-Jacques Ampère

Mother: Jeanne Antoinette Desutières-Sarcey Ampère

Spouse/Ex: Catherine-Antoinette Carron (m. 1799- died 1803), Jeanne-Françoise Potot (m. 1806)

Early Life

A French physicist who founded and named the science of electrodynamics, now known as electromagnetism, André-Marie Ampère was born on 20 January 1775 to Jean-Jacques Ampère, a prosperous businessman, and Jeanne Antoinette Desutières-Sarcey Ampère, during the height of the French Enlightenment. Ampère made the revolutionary discovery that a wire carrying electric current can attract or repel another wire next to it that’s also carrying electric current. The attraction is magnetic, but no magnets are necessary for the effect to be seen. He went on to formulate Ampere’s Law of electromagnetism and produced the best definition of electric current of his time. His name endures in everyday life in the ampere, the unit for measuring electric current.

Ampère was also an acclaimed mathematician with interests in several other fields like history, philosophy, and natural sciences. Born during the height of the French Enlightenment, he had the fortune of growing up in an intellectually stimulating atmosphere. The France of his youth was marked by wide-spread developments in sciences and arts, and the French Revolution which began when he was a young man also played an influential role in shaping his future life. The son of a prosperous businessman, he was encouraged from a young age to seek knowledge in a variety of subjects. He became fascinated with mathematics and science among other subjects and grew up to become a professor of mathematics. A brilliant man with in-depth knowledge of various subjects, he also taught philosophy and astronomy at the University of Paris. Along with his academic career, Ampere also engaged in scientific experiments in diverse fields and was particularly intrigued by the works of Hans Christian Oersted who had discovered a link between electricity and magnetism. Extending Oersted’s experimental work, Ampere made several more discoveries in the field which became known as electromagnetism or electrodynamics and is regarded as one of the founders of this important branch of theoretical physics.

Ampère is also the inventor of numerous applications, such as the solenoid (a term coined by him) and the electrical telegraph. An autodidact, Ampère was a member of the French Academy of Sciences and professor at the École Polytechnique and the Collège de France. The SI unit of measurement of electric current, the ampere, is named after him. His name is also one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

André-Marie Ampère (/ˈæmpɪər/; French: ɑ̃pɛʁ), was born on 20 January 1775 to Jean-Jacques Ampere and Jeanne Antoinette Desutières-Sarcey Ampere. His father was a prosperous businessman. Ampere had two sisters. His father greatly admired the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau who believed that young boys should avoid formal schooling and pursue instead an “education direct from nature”. Thus he did not send his son to school and instead let him educate himself with the help of the books in his well-stocked library.

When André-Marie was five years old, his family moved to a country estate near the village of Poleymieux about six miles (10 km) from Lyon. His father had grown so wealthy that he no longer needed to spend much time in the city. A second daughter Josephine was born when André-Marie was eight.

As a child, Ampere was very curious and developed an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He became a voracious reader under the guidance of his father and read books on mathematics, history, travels, poetry, philosophy, and the natural sciences. Along with his interest in the sciences, he also became interested in the Catholic faith as his mother was a very devout woman. He was particularly fascinated by mathematics and began studying the subject seriously when he was 13. His father encouraged his intellectual pursuits and obtained specialized books on the subject for him, and arranged for him to get formal lessons in calculus from Abbot Daburon. During this time Andre also began studying physics.

The French Revolution (1787-99) that erupted during his youth was also formative. Ampère’s father was called into public service by the new revolutionary government, becoming a justice of the peace in a small town near Lyon. Yet when the Jacobin faction seized control of the Revolutionary government in 1792, Jean-Jacques Ampère resisted the new political tides, and he was guillotined on November 24, 1793, as part of the Jacobin purges of the period. His family suffered a tragedy when one of his sisters died in 1792. Another tragedy followed when the Jacobin faction seized control of the Revolutionary government in 1792 and guillotined his father in November 1793. Devastated by these terrible losses, he abandoned his studies for a year.

Personal Life

In 1799, aged 24, André-Marie Ampère married 25-year-old Catherine-Antoinette Carron, who was usually called Julie. A year later, their son Jean-Jacques was born he was named in memory of Ampère’s beloved father. Tragedy struck Ampère when, after less than four years of marriage, Julie died in 1803 of abdominal cancer.

André-Marie Ampère got married again in 1806, to Jeanne-Françoise Potot. The couple quickly realized their marriage had been a mistake. Their daughter Albine was born in 1807, and the couple legally separated in 1808. Albine came to live with her father and his younger sister Josephine.

Ampère’s son, Jean-Jacques, became a notable professor of linguistics and a member of the French Academy. He and his father were known to have rather explosive arguments with one another, both having quick tempers.

Career and Works

André-Marie Ampère started working as a private mathematics tutor in Lyon in 1797. He proved to be an excellent teacher and students began flocking to him for guidance in no time. His success as a tuition teacher brought him to the attention of the intellectuals in Lyon who was greatly impressed by the young man’s knowledge.

Ampère took his first regular job in 1799 as a mathematics teacher, which gave him the financial security to marry Carron and father his first child, Jean-Jacques (named after his father), the next year. (Jean-Jacques Ampère eventually achieved his own fame as a scholar of languages). Ampère’s maturation corresponded with the transition to the Napoleonic regime in France, and the young father and teacher found new opportunities for success within the technocratic structures favored by the new French First Consul.

In 1802 Ampère was appointed a professor of physics and chemistry at the École Centrale in Bourg-en-Bresse, leaving his ailing wife and infant son Jean-Jacques Antoine Ampère in Lyon. He used his time in Bourg to research mathematics, producing Considérations sur la théorie mathématique de jeu (1802; “Considerations on the Mathematical Theory of Games”), a treatise on the mathematical probability that he sent to the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1803.

Ampère obtained a teaching position at the recently opened École Polytechnique in 1804. He was much success in this position and was appointed a professor of mathematics at the school in 1809 despite his lack of formal qualifications, a position he would hold till 1828. Ampere was elected to the French Academy of Sciences in 1814. He also engaged in scientific and mathematical research alongside his academic career and taught subjects like philosophy and astronomy at the University of Paris in 1819-20. He was elected to the prestigious chair in experimental physics at the Collège de France in 1824.

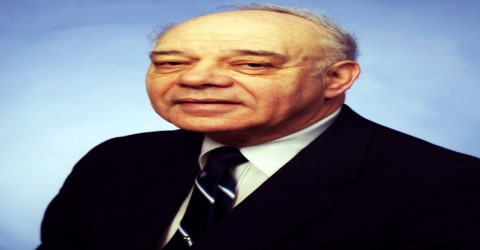

In April 1820, Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted discovered that a flow of electric current in a wire could deflect a nearby magnetic compass needle. Oersted had discovered a link between electricity and magnetism-electromagnetism. In September 1820, François Arago demonstrated Oersted’s electromagnetic effect to France’s scientific elite at the French Academy in Paris. Ampère was present, having been elected to the Academy in 1814. Ampère was fascinated by Oersted’s discovery and decided he would try to understand why electric current produced a magnetic effect.

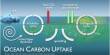

Ampère was fascinated by Oersted’s electromagnetic discoveries and began working on them himself. After rigorous experiments, Ampere showed that two parallel wires carrying electric currents attract or repel each other, depending on whether the currents flow in the same or opposite directions, respectively. Gifted in both mathematics and physics, Ampere applied mathematics in generalizing physical laws from these experimental results, and discovered the principle that came to be called “Ampere’s law”. His works provided a physical understanding of the electromagnetic relationship, theorizing the existence of an “electrodynamic molecule” that served as the component element of both electricity and magnetism.

Ampère immediately set to work developing a mathematical and physical theory to understand the relationship between electricity and magnetism. Extending Ørsted’s experimental work, Ampère showed that two parallel wires carrying electric currents repel or attract each other, depending on whether the currents flow in the same or opposite directions, respectively. He also applied mathematics in generalizing physical laws from these experimental results. Most important was the principle that came to be called Ampère’s law, which states that the mutual action of two lengths of current-carrying wire is proportional to their lengths and to the intensities of their currents. Ampère also applied this same principle to magnetism, showing the harmony between his law and French physicist Charles Augustin de Coulomb’s law of magnetic action. Ampère’s devotion to, and skill with, experimental techniques anchored his science within the emerging fields of experimental physics.

To explain the relationship between electricity and magnetism, Ampère proposed the existence of a new particle responsible for both of these phenomena – the electrodynamic molecule, a microscopic charged particle we can think of as a prototype of the electron. Ampère correctly believed that huge numbers of these electrodynamic molecules were moving in electric conductors, causing electric and magnetic phenomena.

Ampère also provided a physical understanding of the electromagnetic relationship, theorizing the existence of an “electrodynamic molecule” (the forerunner of the idea of the electron) that served as the component element of both electricity and magnetism. Using this physical explanation of electromagnetic motion, Ampère developed a physical account of electromagnetic phenomena that was both empirically demonstrable and mathematically predictive. In 1824, Ampère was appointed to the Chair of Experimental Physics at the Collège de France in Paris, which he occupied for the rest of his life.

In 1827 Ampère published his magnum opus, Mémoire sur la théorie mathématique des phénomènes électrodynamiques uniquement déduite de l’experience (Memoir on the Mathematical Theory of Electrodynamic Phenomena, Uniquely Deduced from Experience), the work that coined the name of his new science, electrodynamics, and became known ever after as its founding treatise.

Ampère discovered and named the element fluorine. In 1810, he proposed that the compound we now call hydrogen fluoride consisted of hydrogen and a new element: the new element had similar properties to chlorine he said. He and Humphry Davy, who was British, entered into correspondence (even though France and Britain were at war). Ampère proposed that fluorine could be isolated by electrolysis, which Davy had previously used to discover elements such as sodium and potassium. It was only in 1886 that French chemist Henri Moissan finally isolated fluorine. He achieved this using electrolysis, the method Ampère had recommended.

Awards and Honor

In 1827 André-Marie Ampère was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society and in 1828, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science.

Ampère’s name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower. Several items are named after Ampère; many streets and squares, schools, a Lyon metro station, and an electric ferry in Norway.

Death and Legacy

At the age of 61, André-Marie Ampère caught pneumonia. He died in the French Mediterranean city of Marseilles on June 10, 1836. He was buried in Marseilles, but his remains were later moved to the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. Many other illustrious people are buried in Montmartre Cemetery, including the composers Hector Berlioz and Jacques Offenbach; the artist Edgar Degas; the author Émile Zola; the physicist Léon Foucault; the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam; and Ampère’s son, Jean-Jacques, who is buried next to his father.

Ampère formulated Ampere’s Law which states that the mutual action of two lengths of current-carrying wire is proportional to their lengths and to the intensities of their currents. He is considered the first person to discover electromagnetism. One of his major contributions to classical electromagnetism was Ampere’s circuital law, which relates the integrated magnetic field around a closed loop to the electric current passing through the loop. He is credited for the invention of the astatic needle, a vital component of the modern astatic galvanometer.

The 1827 publication of Ampère’s synoptic Mémoire brought to a close his feverish work over the previous seven years on the new science of electrodynamics. The text also marked the end of his original scientific work. His health began to fail, and he died while performing a university inspection, decades before his new science was canonized as the foundation stone for the modern science of electromagnetism.

In recognition of his contribution to the creation of modern electrical science, an international convention, signed at the 1881 International Exposition of Electricity, established the ampere as a standard unit of electrical measurement, along with the coulomb, volt, ohm, and watt, which are named, respectively, after Ampère’s contemporaries Charles-Augustin de Coulomb of France, Alessandro Volta of Italy, Georg Ohm of Germany, and James Watt of Scotland.

Information Source: