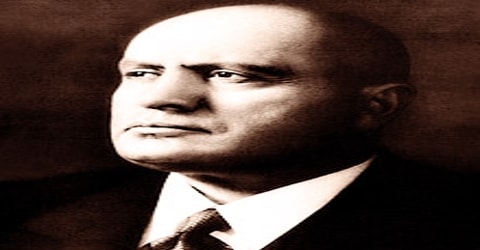

Biography of Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini – Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Italy.

Name: Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini

Date of Birth: July 29, 1883

Place of Birth: Predappio, Italy

Date of Death: April 28, 1945 (aged 61)

Place of Death: Giulino, Azzano, Italy

Occupation: Politician, Journalist, Novelist, Teacher

Father: Alessandro Mussolini

Mother: Rosa Maltoni

Spouse/Ex: da Dalser (m. 1914), Rachele Guidi (m. 1915)

Children: 6

Early Life

An Italian prime minister (1922-43) and the first of 20th-century Europe’s fascist dictators, Benito Mussolini was born at Dovia di Predappio, Italy, on 29th July 1883. As dictator of Italy and founder of fascism, Mussolini inspired several totalitarian rulers such as Adolf Hitler. A journalist and politician, Mussolini had been a leading member of the National Directorate of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from 1910 to 1914 but was expelled from the PSI for advocating military intervention in World War I, in opposition to the party’s stance on neutrality. He led Italy into three straight wars, the last of which led to his overthrow by his own people.

Even though Mussolini made a name and career in socialism, working for the Italian Socialist Party and writing for socialist newspapers, he was later expelled from the party due to his support for World War I, following which he formed the Fascist Party to re-build Italy as a strong European power. After the ‘March on Rome’ in October 1922, he became the Prime Minister and gradually destroyed all political opposition. Thereafter, he consolidated his position through a series of laws and turned Italy into a one-party dictatorship. Mussolini remained in power until he was deposed in 1943. He later became the leader of the Italian Social Republic, which was a German supported regime in northern Italy. He held this post until his death in 1945.

Mussolini’s foreign policy aimed to expand the sphere of influence of Italian fascism. In 1923, he began the “Pacification of Libya” and ordered the bombing of Corfu in retaliation for the murder of an Italian general. In 1936, Mussolini formed Italian East Africa (AOI) by merging Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia following the Abyssinian crisis and the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. Between 1936 and 1939, Mussolini ordered the successful Italian military intervention in Spain in favor of Francisco Franco during the Spanish civil war.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Benito Mussolini, in full Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (Italian: beˈniːto mussoˈliːni), byname Il Duce (Italian: “The Leader”), was born on 29th July 1883 in Dovia di Predappio in Forli province, Northern Italy, to blacksmith and socialist Alessandro Mussolini and pious Catholic elementary school teacher Rosa Mussolini. They lived in two crowded rooms on the second floor of a small, decrepit palazzo; and, because Mussolini’s father spent much of his time discussing politics in taverns and most of his money on his mistress, the meals that his three children ate were often meager.

As a young boy, Mussolini would spend some time helping his father in his smithy. Mussolini’s early political views were strongly influenced by his father, who idolized 19th-century Italian nationalist figures with humanist tendencies such as Carlo Pisacane, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi. His father’s political outlook combined views of anarchist figures such as Carlo Cafiero and Mikhail Bakunin, the military authoritarianism of Garibaldi, and the nationalism of Mazzini.

Mussolini was short-tempered and disobedient and expelled twice from school for stabbing fellow students with a penknife, he managed to get good scores and obtain a teaching certificate in 1901. He went to Switzerland in 1902 to avoid military service, where he associated with other socialists. Mussolini returned to Italy in 1904, spent time in the military, and engaged in politics full time thereafter.

Personal Life

Benito Mussolini’s first wife was Ida Dalser, whom he married in Trento in 1914. The couple had a son the following year and named him Benito Albino Mussolini.

Mussolini romanced Rachele Guidi and fathered a daughter, Edda, in 1910. He married her in 1915 and further had four children; son Vittorio (1916), son Bruno (1918), son Romano (1927) and daughter Anna Maria (1929).

Mussolini had several mistresses, among them Margherita Sarfatti and his final companion, Clara Petacci. Mussolini had many brief sexual encounters with female supporters, as reported by his biographer Nicholas Farrell. Imprisonment likely caused Mussolini’s claustrophobia. He refused to enter the Blue Grotto (a sea cave on the coast of Capri) and preferred large rooms like his 60 by 40 by 40 feet (18 by 12 by 12 m) office at the Palazzo Venezia.

Career and Works

Benito Mussolini had become a member of the Socialist Party in 1900 and had begun to attract wide admiration. In speeches and articles, Mussolini was extreme and violent, urging revolution at any cost, but he was also well spoken. Mussolini held several posts as editor and labor leader until he emerged in the 1912 Socialist Party Congress. He became editor of the party’s daily paper, Avanti, at the age of twenty-nine. His powerful writing injected excitement into the Socialist ranks. In a party that had accomplished little in recent years, his youth and his intense nature was an advantage. He called for the revolution at a time when revolutionary feelings were sweeping the country.

In 1904, Mussolini was arrested by the Swiss authorities and deported to Italy, following which he joined the Italian army, but left in 1906 to resume teaching and journalism. He moved to Trento, in the then-Austria-Hungary, and worked for a local socialist party. For the next couple of years, he worked as an editor and labor reader, gaining a reputation for his views on nationalism and militarism.

After writing in a wide variety of socialist papers, Mussolini founded a newspaper of his own, La Lotta di Classe (“The Class Struggle”). So successful was this paper that in 1912 he was appointed the editor of the official Socialist newspaper, Avanti! (“Forward!”), whose circulation he soon doubled; and as its antimilitarist, antinationalist, and anti-imperialist editor, he thunderously opposed Italy’s intervention in World War I.

Benito Mussolini thought of himself as an intellectual and was considered to be well-read. He read avidly; his favorites in European philosophy included Sorel, the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, French Socialist Gustave Hervé, Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta, and German philosophers Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the founders of Marxism. Mussolini had taught himself French and German and translated excerpts from Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, and Kant. During this time, he published “Il Trentino veduto da un Socialista” (“Trentino as seen by a Socialist”) in the radical periodical La Voce. He also wrote several essays about German literature, some stories, and one novel: L’amante del Cardinale: Claudia Particella, romanzo Storico (The Cardinal’s Mistress). This novel he co-wrote with Santi Corvaja, and it was published as a serial book in the Trento newspaper Il Popolo. It was released in installments from 20 January to 11 May 1910. The novel was bitterly anticlerical, and years later was withdrawn from circulation after Mussolini made a truce with the Vatican.

In 1914, Benito Mussolini deserted the Socialist Party to cross over to the enemy camp, the Italian middle class. He knew that World War I (1914-18) would bury old Europe, and he began to prepare for “the unknown.” In late 1914 he founded an independent newspaper, Popolo d’Italia, and backed it up with his own movement, the Autonomous Fascists. He drew close to the new forces in Italian politics, the extreme middle-class youth, and he made himself their spokesman. The Italian working class now called Mussolini “Judas” and “traitor.” In 1917, Mussolini was wounded during army training, but he managed to return to politics that same year. His newspaper, which he now backed with a second political movement, Revolutionary Fascists, was his main strength. After the war, Mussolini’s career declined. He organized his third movement, Constituent Fascists, in 1918, but it did not survive. Mussolini ran for office in the 1919 parliamentary elections but was defeated.

Benito Mussolini published Giovanni Hus, il veridico (Jan Hus, true prophet), an historical and political biography about the life and mission of the Czech ecclesiastic reformer Jan Hus and his militant followers, the Hussites, in 1913. During this socialist period of his life, Mussolini sometimes used the pen name “Vero Eretico” (“sincere heretic”). Mussolini rejected egalitarianism, a core doctrine of socialism. He was influenced by Nietzsche’s anti-Christian ideas and negation of God’s existence. Mussolini felt that socialism had faltered, in view of the failures of Marxist determinism and social democratic reformism, and believed that Nietzsche’s ideas would strengthen socialism. While associated with socialism, Mussolini’s writings eventually indicated that he had abandoned Marxism and egalitarianism in favor of Nietzsche’s übermensch concept and anti-egalitarianism.

Benito Mussolini founded another movement, Fighting Fascists, won the favor of the Italian youth and waited for events to favor him, in March 1919. The elections in 1921 sent him to Parliament at the head of thirty-five Fascist deputies; the third assembly of his movement gave birth to a national party, the National Fascist Party, with more than 250 thousand followers and Mussolini as its uncontested leader. Mussolini successfully marched into Rome, Italy, in October 1922. He now enjoyed the support of key groups (industry, farmers, military, and church), whose members accepted Mussolini’s solution to their problems: organize middle-class youth, control workers harshly, and set up a tough central government to restore “law and order.” Thereafter, Mussolini attacked the workers and spilled their blood over Italy. It was the complete opposite of his early views of socialism.

Mussolini obtained full dictatorial powers for a year, and in that year he pushed through a law that enabled the Fascists to cement a majority in the parliament. The elections in 1924, though undoubtedly fraudulent, secured his personal power. Many Italians, especially among the middle class, welcomed his authority. They were tired of strikes and riots, responsive to the flamboyant techniques and medieval trappings of fascism, and ready to submit to dictatorship, provided the national economy was stabilized and their country restored to its dignity. He suspended civil liberties, destroyed all opposition, and imposed open dictatorship (absolute rule).

On 31st December 1924, MVSN consuls met with Benito Mussolini and gave him an ultimatum: crush the opposition or they would do so without him. Fearing a revolt by his own militants, Mussolini decided to drop all pretense of democracy. Mussolini’s henchmen kidnapped and murdered the Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti, who had become one of fascism’s most effective critics in parliament, in 1924. The Matteotti crisis shook Mussolini, but he managed to maintain his hold on power. On 3rd January 1925, Mussolini made a truculent speech before the Chamber in which he took responsibility for squadristi violence (though he did not mention the assassination of Matteotti). He did not abolish the squadristi until 1927, however.

In 1929 Mussolini’s Concordat with the Vatican settled the historic differences between the Italian state and the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Pius XI (1857-1939) said that Mussolini had been sent “by Divine Providence.” As the 1930s began, Mussolini was seated safely in power and enjoyed wide support. The strongest groups who had put Mussolini into power now profited from it. However, the living standard of the working majority fell; the average Italian worker’s income amounted to one-half of that of a worker in France, one-third of that of a worker in England, and one-fourth of that of a worker in America. As a national leader, Mussolini offered no solutions for Italy’s problems. He surrounded himself with ambitious and greedy people and let them bleed Italy dry while his secret agents gathered information on opponents.

Benito Mussolini was hailed as a genius and a superman by public figures worldwide. His achievements were considered little less than miraculous. He had transformed and reinvigorated his divided and demoralized country; he had carried out his social reforms and public works without losing the support of the industrialists and landowners; he had even succeeded in coming to terms with the papacy. The reality, however, was far less rosy than the propaganda made it appear. Social divisions remained enormous, and little was done to address the deep-rooted structural problems of the Italian state and economy.

Mussolini grew popular among key groups; industry, military, church, and farmers, who were benefitted by his public works programs and employment plans. For a decade, peace prevailed in Italy. Since he wanted to transform Italy into a mighty empire, he invaded Ethiopia in 1935, using mustard gas. The Ethiopians surrendered to his modern tanks and airplanes and eventually, Ethiopia was added to his new Empire in 1936. With hopes of further increasing his influence and extending his empire, he sent troops and arms to the Nationalists in Spain during the Spanish Civil War in 1939.

Benito Mussolini also initiated the “Battle for Land”, a policy based on land reclamation outlined in 1928. The initiative had a mixed success; while projects such as the draining of the Pontine Marsh in 1935 for agriculture were good for propaganda purposes, provided work for the unemployed and allowed for great land owners to control subsidies, other areas in the Battle for Land were not very successful. This program was inconsistent with the Battle for Wheat (small plots of land were inappropriately allocated for large-scale wheat production), and the Pontine Marsh was lost during World War II. Fewer than 10,000 peasants resettled on the redistributed land, and peasant poverty remained high. The Battle for Land initiative was abandoned in 1940.

Mussolini reacted at first with a public works program but soon shifted to foreign adventure. The 1935 Ethiopian War was planned to direct attention away from internal problems. The “Italian Empire,” Mussolini’s creation, was announced in 1936. The 1936 Spanish intervention, in which Mussolini aided Francisco Franco (1892-1975) in Spain’s civil war, followed but had no benefit for Italy. Mussolini then joined forces with German dictator Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and in 1938 began to attack Jewish people within the country just as Germany was doing. As the 1930s ended, Mussolini was losing all his support within Italy.

Impressed with his successful invasions, German dictator Adolf Hitler collaborated with Benito Mussolini on a military alliance called ‘Pact of Steel’ in 1939, following which he imposed anti-Jewish legislation in Italy. His declaration of war on France and Britain in 1940 exposed his weaknesses in military equipment and army. The military position of Italy was in a bad shape by early 1942 and during the summer of 1943, the Allied troops invaded Sicily, in the Mediterranean Sea, hoping to oust Mussolini from power. The Allied Forces progressed further dropping bombs on Rome, resulting in his arrest in July 1943 and imprisonment at a mountain ski resort in Abruzzo. However, Mussolini was rescued by German commandos soon after. In September 1943, he was declared the head of a puppet government of Italian Social Republic, in Northern Italy, which was controlled by Germany. He held this post until 1945.

Death and Legacy

In April 1945, while attempting to escape to Spain en-route Switzerland, Benito Mussolini and Petacci were captured by the Italian partisans. Mussolini was finally executed by a firing squad on 28th April 1945, at Dongo in Como province, along with other members of their party. Their bodies were brought to Milan on 29th April 1945 and hung upside down in public from the roof of a fueling station as proof of their death. Mussolini was buried in an unmarked grave in the Musocco cemetery, to the north of the city. On Easter Sunday 1946, his body was located and dug up by Domenico Leccisi and two other neo-Fascists.

Benito Mussolini formed a single, national group, Fasci di Combattimento (Fascist Party), in 1919 to reconstruct Italy into a strong European power. He formed a coalition government and became the youngest prime minister of Italy, in October 1922, at the age of 39, a record he held until Matteo Renzi was appointed in February 2014.

The great mass of the Italian people greeted Benito Mussolini’s death without regret. He had lived beyond his time and had dragged his country into a disastrous war, which it was unwilling and unready to fight. Democracy was restored in the country after 20 years of dictatorship, and a neo-Fascist Party that carried on Mussolini’s ideas won only 2 percent of the vote in the 1948 elections.

Benito Mussolini’s life has been adapted into several movies, such as ‘The Great Dictator’ (1940), ‘Mussolini: Ultimo Atto’ (1974), ‘Mussolini and I’ (1985), ‘Benito’ (1993), an award-winning Italian film ‘Vincere’ (2009). His life has been depicted on television as well – the most famous being the mini-series ‘Mussolini: The Untold Story’ (1985) and ‘Il Duce Canadese’ (2004).

Information Source: