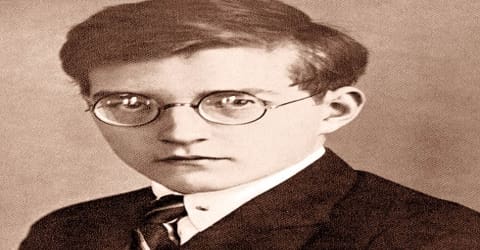

Biography of Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich – Russian composer and pianist.

Name: Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich

Date of Birth: September 25, 1906

Place of Birth: Saint Petersburg, Russia

Date of Death: August 9, 1975

Place of Death: Moscow, Russia

Occupation: Composer, Pianist

Father: Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich

Mother: Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina

Spouse/Ex: Irina Antonovna Shostakovich (M. 1962–1975), Margarita Kainova (M. 1956–1960), Nina Vassilyevna Varzar (M. 1932–1954)

Children: Maxim Shostakovich, Galina Dmitrievna Shostakovich

Early Life

Dmitry Shostakovich, Russian composer, is best known for his long body of works, which includes several operas, 15 symphonies, numerous chamber works, and concerti, was born on 25th September 1906, in Saint Petersburg, Russia. He achieved fame in the Soviet Union under the patronage of Soviet chief of staff Mikhail Tukhachevsky, but later had a complex and difficult relationship with the government. Nevertheless, he received accolades and state awards and served in the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947) and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (from 1962 until his death).

With the empowerment of Joseph Stalin, the freedom of the artists and the composers were curbed and were forced to stop writing music. Shostakovich was one among them. His opera ‘Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District’ was initially accepted but was later panned by the critics as Stalin disapproved of it. Shostakovich’s works highlighted the challenging issues that were beyond music. His works also threw light on the role of the artist and the dilemma of humanity in the face of war and the hapless state of being oppressed during the most unfair century.

A polystylist, Shostakovich developed a hybrid voice, combining a variety of different musical techniques into his works. His music is characterized by sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque, and ambivalent tonality; the composer was also heavily influenced by the neo-classical style pioneered by Igor Stravinsky, and (especially in his symphonies) by the late Romanticism of Gustav Mahler.

His orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti. His chamber output includes 15 string quartets, a piano quintet, two piano trios, and two pieces for string octet. His solo piano works include two sonatas, an early set of preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Other works include three operas, several song cycles, ballets, and a substantial quantity of film music; especially well known is The Second Waltz, Op. 99, music to the film The First Echelon (1955–1956), as well as the suites of music composed for The Gadfly.

Shostakovich was extremely modest and did not comment on his music. He was basically quite nervous, which could be due to the terrors he faced during his lifetime. His works exemplifies the classic forms of the twentieth century, as his style evolved from humor to more reclusive melancholy and patriotic dedication and later to depressing mood during his last stages.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Dmitry Shostakovich, in full Dmitry Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, was born on September 12 (Sept. 25, New Style), 1906, St. Petersburg, Russia. He was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich’s paternal grandfather, originally surnamed Szostakowicz, was of Polish Roman Catholic descent (his family roots trace to the region of the town of Vileyka in today’s Belarus), but his immediate forebears came from Siberia.

Shostakovich began piano lessons with his mother at 9 years old. He was an incredibly gifted musician and was admitted to the Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) Conservatory at 13. His composition studies were the beginning of his imposed state guidance: his teachers tried to influence his work in the classic Russian style like Borodin, Risky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Cui, and Balakirev. Instead, Shostakovich favored to work of Prokofiev and Stravinsky, putting him at odds with the preferred compositional style. Shostakovich also attended Alexander Ossovsky’s music history classes. Steinberg tried to guide Shostakovich on the path of the great Russian composers but was disappointed to see him ‘wasting’ his talent and imitating Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev. Shostakovich also suffered for his perceived lack of political zeal, and initially failed his exam in Marxist methodology in 1926.

His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered 1926), written as his graduation piece at the age of 19. This work brought him to the attention of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who helped Shostakovich find accommodation and work in Moscow, and sent a driver around in “a very stylish automobile” to take him to a concert.

He participated in the Chopin International Competition for Pianists in Warsaw in 1927 and received an honorable mention but made no subsequent attempt to pursue the career of a virtuoso, confining his public appearances as a pianist to performances of his own works.

Personal Life

In the year 1927, Dmitri Shostakovich entered into a relationship with Ivan Sollertinsky, who was his close friend. However, the friendship was cut short with her death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced Shostakovich to the music of Gustav Mahler that strongly influenced his music right from Fourth Symphony onwards. In the year 1932, Shostakovich married Nina Varzar but this relation did not seem to get along well. Thus, in 1935, their relation ended leading to a divorce but soon they remarried and Nina gave birth to their first child.

Shostakovich had two children, Maxim and Galina. Interestingly, Maxim continued the family trade and became a pianist and conductor, and Maxim’s son Dmitri is also a pianist. Shostakovich was a nervous, anxious, and (perhaps) obsessive man. He was frequently ill, due to nerves. He was also eager to please, which makes his oscillation from critical acclaim to denouncement, acclaim, denouncement, and finally acclaim again peculiar.

Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter he was “obsessed with cleanliness”. He synchronized the clocks in his apartment and regularly sent cards to himself to test how well the postal service was working. Elizabeth Wilson’s Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (1994 edition) indexes 26 references to his nervousness. Mikhail Druskin remembers that even as a young man the composer was “fragile and nervously agile”. Yuri Lyubimov comments, “The fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius.” In later life, Krzysztof Meyer recalled, “his face was a bag of tics and grimaces.”

Career and Works

Shostakovich’s first symphony (premiered 1926) was seen as a critical success at the time of its performance, especially given that he composed it at 19 as his graduation piece from the Petrograd Conservatory. His next two symphonies were less critically acclaimed, due to their more experimental harmonic nature. Shostakovich’s music was equal parts classical, satirical, and grotesque, as will be explored later. This work brought him to the attention of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who helped Shostakovich find accommodation and work in Moscow, and sent a driver around in “a very stylish automobile” to take him to a concert.

Shostakovich took up a job as a concert pianist and composer after graduating but failed to impress his audiences with his dry style of playing. He was awarded ‘honorable mention’ at the First International Frederic Chopin Piano Competition in 1927 at Warsaw. There were other appreciations that came in Shostakovich’s way like that of Leopold Stokowski who premiered his first recording in the US. Bruno Walter, the conductor, was also impressed by Shostakovich’s composition of ‘First Symphony’, which was conducted at Berlin in the same year. Shostakovich thus focused more on composition and only performed his works.

His style evolved from the brash humor and experimental character of his first period, exemplified by the operas The Nose and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, into both the more introverted melancholy and nationalistic fervor of his second phase (the Symphonies No. 5 and No. 7, “Leningrad”), and finally into the defiant and bleak mood of his last period (exemplified by the Symphony No. 14 and Quartet No. 15).

In 1927 Shostakovich wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a great pro-Soviet choral finale. Owing to its experimental nature, as with the subsequent Third Symphony, it was not critically acclaimed with the enthusiasm given to the First. While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Nikolai Gogol. In June 1929, against the composer’s own wishes, the opera was given a concert performance; it was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM). Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension among musicians.

Shostakovich’s first opera was called, ‘The Nose’ and it was poorly received critically. ‘Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District’ (1934) was Shostakovich’s second opera, and it stands as an important tipping point in Shostakovich’s career as a composer. Specifically, in 1936 it was criticized by the party leadership in the state-run newspaper Pravda in the article ‘Muddle Instead of Music.’ Ironically, up to this point, the composition was seen as a socialist success, an exemplar of Socialist realism. It appears that Stalin and other party leadership that was at a performance were startled by the loud noises in the brass and percussion. This denouncement led to a ‘voluntary withdrawal’ of his fourth symphony (voluntary like do this or we’ll do it for you…). We’ll look later at what made his music perhaps too avant-garde for the state.

From 1928, when Joseph Stalin inaugurated his First Five-Year Plan, an iron hand fastened on Soviet culture, and in music, a direct and popular style was demanded. Avant-garde music and jazz were officially banned in 1932, and for a while even the stylistically unproblematic Tchaikovsky was out of favor, owing to his quasi-official status in tsarist Russia. Shostakovich did not experience immediate official displeasure, but when it came it was devastating. It has been said that Stalin’s anger at what he heard when he attended a performance of Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1936 precipitated the official condemnation of the opera and of its creator.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which was first performed in 1934. It was immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as “the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party”, and as an opera that “could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture”.

He was bitterly attacked in the official press, and both the opera and the still unperformed Symphony No. 4 (1935–36) were withdrawn. The composer’s next major work was his Symphony No. 5 (1937), which was described in the press as “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism.” A trivial, dutifully “optimistic” work might have been expected; what emerged was compounded largely of serious, even sombre and elegiac music, presented with a compelling directness that scored an immediate success with both the public and the authorities.

With his fifth symphony (1937) Shostakovich came back into the good graces of the state. The piece is largely tuneful and conservative. Critics claimed he learned from his mistakes. It could be argued he simply learned how to further hide his intent. Either way, his music was back in favor with the state, and he no longer needed to fear for his life. Unfortunately, it only lasted so long. During 1936 and 1937, in order to maintain as low a profile as possible between the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, Shostakovich mainly composed film music, a genre favored by Stalin and lacking in dangerous personal expression.

The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony. The work marked a great shift in style, owing to the substantial influence of Mahler and a number of Western-style elements. The symphony gave Shostakovich compositional trouble, as he attempted to reform his style into a new idiom. The composer was well into the work when the Pravda article appeared. He continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but after a number of rehearsals Shostakovich, for reasons still debated today, decided to withdraw the symphony from the public. A number of his friends and colleagues, such as Isaak Glikman, have suggested that it was, in fact, an official ban that Shostakovich was persuaded to present as a voluntary withdrawal.

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony was subtitled as ‘A Soviet Artist’s Reply to Just Criticism’ in 1937. Later, in 1941, Shostakovich was inspired by the German invasion of Russia and composed ‘Seventh Symphony’, which was subtitled as ‘Leningrad’. This work was well received and appreciated worldwide and his picture appeared on the cover of Times Magazine. Hence, it was disheartening when this work finally fell into obscurity.

The 1941 German invasion of Russia inspired the composer’s Seventh Symphony, subtitled “Leningrad.” Impressed by the symphony’s epic-heroic character, Toscanini, Koussevitzky, and Stokowski vied for the Western Hemisphere premiere; the score had to be microfilmed, flown to Teheran, driven to Cairo, and flown out. The work became an enormous success the world over but eventually fell into obscurity. Still, the composer had for a time become a worldwide celebrity, his picture even appearing on the cover of Time.

In 1937 Shostakovich became a teacher of composition in the Leningrad Conservatory, and the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 found him still in that city. He composed his Symphony No. 7 (1941) in beleaguered Leningrad during the latter part of that year and finished it in Kuybyshev (now Samara), to which he and his family had been evacuated. The work achieved quick fame, as much because of the quasi-romantic circumstances of its composition as because of its musical quality. In 1943 Shostakovich settled in Moscow as a teacher of composition at the conservatory, and from 1945 he taught also at the Leningrad Conservatory.

The Ninth Symphony (1945), in contrast, was much lighter in tone. Gavriil Popov wrote that it was “splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!! But by 1946 it too was the subject of criticism. Israel Nestyev asked whether it was the right time for “light and the amusing interlude between Shostakovich’s significant creations, a temporary rejection of great, serious problems for the sake of playful, filigree-trimmed trifles.” The New York World-Telegram of 27 July 1946 was similarly dismissive: “The Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner”. Shostakovich continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio (Op. 67), dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a bittersweet, Jewish-themed totentanz finale. In 1947, the composer was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.

Shostakovich’s works written during the mid-1940s contain some of his best music, especially the Symphony No. 8 (1943), the Piano Trio (1944), and the Violin Concerto No. 1 (1947–48). In Moscow in 1948, at a now notorious conference presided over by Andrey Zhdanov, a prominent Soviet theoretician, the leading figures of Soviet music including Shostakovich were attacked and disgraced. As a result, the quality of Soviet composition slumped in the next few years.

With the issue of an infamous decree in the year 1948 by the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Shostakovich career eclipsed. It accused Shostakovich, Prokofiev and many other renowned composers belonging to the ‘formalist perversions’. After that for a while, he indulged himself in works that glorified Soviet life or history. He was appointed the first secretary of the Soviet Composers Union in 1959.

In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96; it was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics. (His ‘” Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale” was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.) In 1959, he appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union). Later that year, Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic recorded the symphony in Boston for Columbia Records.

His personal influence was reduced by the termination of his teaching activities at both the Moscow and Leningrad conservatories. Yet he was not completely intimidated, and, in his String Quartet No. 4 (1949) and especially his Quartet No. 5 (1951), he offered a splendid rejoinder to those who would have had him renounce completely his style and musical integrity. His Symphony No. 10, composed in 1953, the year of Stalin’s death, flew in the face of Zhdanovism, yet, like his Symphony No. 5 of 16 years earlier, compelled acceptance by sheer quality and directness.

Shostakovich ran afoul of the government again in 1948, when an infamous decree was issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party accusing Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and other prominent composers of “formalist perversions.” For some time he wrote mostly works glorifying Soviet life or history. Artistic repression diminished in post-Stalinist Russia, but curiously Shostakovich still drew in his modernist horns until the Thirteenth Symphony, “Babi Yar,” a 1962 work based on poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko. The work provoked major controversy because of its first movement’s subject: Russian oppression of the Jews.

Yet Shostakovich was undeterred by this, and his deeply impressive Symphony No. 14 (1969), cast as a cycle of 11 songs on the subject of death, was not the sort of work to appeal to official circles. The composer had visited the United States in 1949, and in 1958 he made an extended tour of western Europe, including Italy (where already he had been elected an honorary member of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rome) and Great Britain, where he received an honorary doctorate of music at the University of Oxford.

In 1964 Shostakovich composed the music for the Russian film Hamlet, which was favorably reviewed by The New York Times: “But the lack of this aural stimulation of Shakespeare’s eloquent words is recompensed in some measure by a splendid and stirring musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich. This has great dignity and depth, and at times an appropriate wildness or becoming levity”.

In 1965 Shostakovich raised his voice in defense of poet Joseph Brodsky, who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich co-signed protests together with Yevtushenko and fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. After the protests, the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad.

Shostakovich published his ‘Second Cello Concerto’ in the year 1966, which was a work that was aimed to be at a level higher than that of his first, but it did not capture his audiences’ attention.

That year, Shostakovich was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. He continued to compose, his works growing more sparsely scored and darker, the subject of death becoming prominent. His Fourteenth Symphony (1969), really a collection of songs on texts by Lorca, Apollinaire, Küchelbecker, and Rilke, is a death-obsessed work of considerable dissonance and showing little regard for the Socialist Realism still demanded by the state.

Shostakovich’s last work was his Viola Sonata, which was first performed on 28 December 1975, four months after his death. His musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn’s music shows clear links to Shostakovich’s style of orchestration. His influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars-Erik Larsson.

Dmitry Shostakovich was considered as a strong supporter of communalism. This notion remained intact until the publication of ‘Solomon Volkov’s Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich’ by Solomon Volkov, which was published after his death. Most of the views, which were expressed in Volkov’s book, were regarded as authentic and hence the subject of Shostakovich’s political beliefs continues to be questioned.

Awards and Honor

Dmitri Shostakovich was awarded ‘honorable mention’ at the First International Frederic Chopin Piano Competition in 1927 at Warsaw.

In 1966 Shostakovich was awarded the Royal Philharmonic Society’s, Gold Medal.

Death and Legacy

Dmitri Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975. A civic funeral was held. Even before his death, he had been commemorated with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica.

Dmitri Shostakovich was buried in Moscow’s Novodevichy Cemetery giving full state honors. He was referred to as a loyal communist and was acclaimed as ‘hero of the people’. His music not only revealed his sufferings but also of the pain of the people around him.

Early in his career, his music showed the influence of Prokofiev and Stravinsky, especially in his prodigious and highly successful First Symphony. He could effectively communicate a melancholic depth and profound sense of anguish, as one hears in many of his symphonies, concertos, and quartets. Solomon Volkov, in his controversial Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich explains the composer’s seeming bombast as deft satire of the pomposity of the Soviet state, pointing to the “forced rejoicing” of Fifth Symphony’s ending. Typical traits of Shostakovich’s style include short, reiterated melodic or rhythmic figures, motifs of one or two pitches or intervals, and lugubrious and manic string writing.

Despite the brooding typical of so much of his music, which might suggest an introverted personality, Shostakovich was noted for his gregariousness. After Prokofiev’s death in 1953, he was the undisputed head of Russian music. Since his own death, his music has been the subject of furious contention between those upholding the Soviet view of the composer as a sincere Communist, and those who view him as a closet dissident.

Information Source: