Biography of Eva Peron

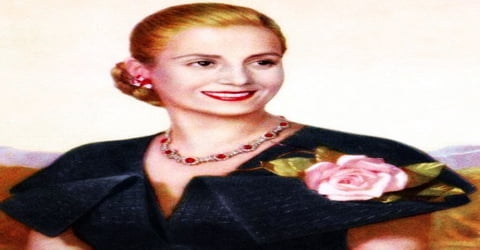

Eva Peron – First Lady of Argentina.

Name: María Eva Duarte de Perón

Date of Birth: May 7, 1919

Place of Birth: Los Toldos, Argentina

Date of Death: 26 July 1952 (aged 33)

Place of Death: Buenos Aires, Argentina

Father: Juan Duarte

Mother: Juana Ibarguren

Spouse: Juan Perón (1945–1952)

Early Life

Eva Perón (First Lady of Argentina from 1946 until her death in 1952) was born on May 7, 1919, in the little village of Los Toldos in Buenos Aires province, Argentina. She was the second wife of President Juan Peron and the First Lady of Argentina. Before entering politics, she was a model and successful radio actress of Argentina. During 1946 presidential election, she campaigned heavily for her husband Juan Peron. During her visit to Spain as part of “Rainbow Tour”, the Spanish government awarded her with the Order of Isabella the Catholic.

At age of 15 in 1934, she moved to the nation’s capital of Buenos Aires to pursue a career as a stage, radio, and film actress. She met Colonel Juan Perón there on 22 January 1944 during a charity event at the Luna Park Stadium to benefit the victims of an earthquake in San Juan, Argentina. The two were married the following year. Juan Perón was elected President of Argentina in 1946; during the next six years, Eva Perón became powerful within the pro-Peronist trade unions, primarily for speaking on behalf of labor rights. She also ran the Ministries of Labor and Health, founded and ran the charitable Eva Perón Foundation, championed women’s suffrage in Argentina, and founded and ran the nation’s first large-scale female political party, the Female Peronist Party.

An important political figure in her own right, she was known for her campaign for female suffrage (the right to vote), her support of organized labor groups, and her organization of a vast social welfare program that benefited and gained the support of the lower classes.

In 1951, Eva Perón announced her candidacy for the Peronist nomination for the office of Vice President of Argentina, receiving great support from the Peronist political base, low-income and working-class Argentines who were referred to as descamisados or “shirtless ones”. However, opposition from the nation’s military and the bourgeoisie, coupled with her declining health, ultimately forced her to withdraw her candidacy. In 1952, shortly before her death from cancer at 33, Eva Perón was given the title of “Spiritual Leader of the Nation” by the Argentine Congress. She was given a state funeral upon her death, a prerogative generally reserved for heads of state.

As a South American first lady, she was the first who featured in a cover story of “Time” magazine. She founded Eva Peron Foundation that worked towards providing scholarships, build homes and hospitals and other charitable work. This organization was also credited for creating Evita City. The organization had a crucial role in Argentina’s health care system.

According to biographers Fraser and Navarro, she played an important role in getting Argentine women the right to vote. As the founder of the Female Peronist Party, she is credited for inspiring a large number of women to take an active part in the politics of Argentina. Her nomination as a candidate for the election of Vice-President angered many military leaders. She was the recipient of the official title of “Spiritual Leader of the Nation”.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Eva Perón, in full Eva Duarte de Perón, née María Eva Duarte, byname Evita, was born on May 7, 1919, in the little village of Los Toldos in Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Her parents, Juan Duarte and Juana Ibarguren, were not married, and her father had a wife and another family. Eva’s family struggled financially, and the situation worsened when Juan died when she was six years old. A few years later they moved to Junín, Argentina.

Initially, they used to live in a one-room apartment there. Later, they shifted to a bigger house. At that time, Evita developed an interest in acting by participating in school plays and concerts. In October 1933, she acted in her school play ‘Students Arise’. After playing this small role, she contemplated pursuing a career in acting and dreamt of becoming a great and successful actress.

At the age of sixteen, Evita, as she was often called, left high school after two years and went to Buenos Aires with the dream of becoming an actress. Lacking any training in the theater, she obtained a few small parts in motion pictures and on the radio. She was finally employed on a regular basis with one of the largest radio stations in Buenos Aires making 150 pesos every month. Her pay had increased to five thousand pesos every month by 1943 and jumped to thirty-five thousand pesos per month in 1944.

In 1934, she escaped to Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, to fulfill her dream of becoming a successful actress. After reaching the capital, she faced lots of difficulties due to lack of formal education and connections.

Personal Life

On 22 January 1944, she met Colonel Juan Peron who was twice her age, at a fundraising programme for earthquake victims. Eva promptly became the colonel’s mistress. Eva referred to the day she met her future husband as her “marvelous day”. Fraser and Navarro write that Juan Perón and Eva left the gala together at around two in the morning.

Eva developed a close relationship with the widowed Perón, who was beginning to organize the Argentine workers in support of his own bid for the presidency. Becoming Perón’s loyal political confidante (one with whom secrets are trusted) and partner, she helped him increase his support among the masses. In October 1945, after Perón was arrested and put in prison by a group of military men who did not support him, she helped to organize a mass demonstration that led to his release.

On 18 October 1945, they got married in a civil ceremony. Later, they had a church wedding on 9 December 1945.

Now politically stronger than ever, Perón became the government candidate in the February 1946 presidential election. Señora de Perón participated actively in the campaign, something no Argentine woman had ever done. She directed her appeal to the less privileged groups of Argentine society, whom she labeled “los descamisados” (the shirtless ones).

As a model, Eva was in a relationship with a number of men. She used some of these men to achieve her modeling assignments. She earned severe criticism for her exploitative mentality towards these men.

Career and Works

In Buenos Aires, Eva’s debut performance on stage was in the play ‘The Perezes Misses’ at the Comedias Theatre on 28 March 1935. In 1936, she went on a national tour with a theatre company. She also worked as a model and got an offer of acting in a few B-grade films. The turning point of her career came when she got the offer of a daily role in a radio drama titled ‘Muy bien’, broadcast on World Radio.

Later that year, she signed a five-year contract with Radio Belgrano, which assured her a role in a popular historical-drama program called Great Women of History, in which she played Elizabeth I of England, Sarah Bernhardt, and the last Tsarina of Russia. Eventually, Eva Duarte came to co-own the radio company. By 1943, Eva Duarte was earning five or six thousand pesos a month, making her one of the highest-paid radio actresses in the nation. Pablo Raccioppi, who jointly ran Radio El Mundo with Eva Duarte, is said to have not liked her, but to have noted that she was “thoroughly dependable”. Eva also had a short-lived film career, but none of the films in which she appeared were hugely successful. In one of her last films, La cabalgata del Circo (The Circus Cavalcade), Eva played a young country girl who rivaled an older woman, the movie’s star, Libertad Lamarque.

At that time, she even became the co-owner of the radio company. Apart from that, she also acted in a few movies which did not receive much success. By 1943, she became one of the highest paid radio actresses in the country. As a result of her success with radio dramas and the films, Eva achieved some financial stability. In 1942, she was able to move into her own apartment in the exclusive neighborhood of Recoleta, on 1567 Calle Posadas.

The next year Eva began her career in politics, as one of the founders of the Argentine Radio Syndicate (ARA). In 1944, she was selected as the President of the broadcast performers’ union.

As a president of this union, she started a daily program titled ‘Toward a Better Future’, a soap opera based on the accomplishments of Juan Peron, a Colonel. After her marriage with Juan Peron, she led a powerful campaign for her husband during the 1946 presidential bid.

On 9 October 1945 Juan Perón was arrested by his opponents within the government who feared that, due to the strong support of the descamisados, the workers and the poor of the nation, Perón’s popularity might eclipse that of the sitting president.

Following Perón’s election, Eva began to play an increasingly important role in the political affairs of the nation. During the early months of the Perón administration, she launched an active campaign for national women’s suffrage, which had been one of Perón’s campaign promises. Due largely to her efforts, suffrage for women became law in 1947, and in 1951 women voted for the first time in a national election.

Six days later, between 250,000 and 350,000 people gathered in front of the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s government house, to demand Juan Perón’s release, and their wish was granted. At 11 pm, Juan Perón stepped onto the balcony of the Casa Rosada and addressed the crowd. Biographer Robert D. Crassweller claims that this moment was particularly powerful because it dramatically recalled important aspects of Argentine history. Crassweller writes that Juan Perón enacted the role of a caudillo addressing his people in the tradition of Argentine leaders Rosas and Yrigoyen. Crassweller also claims that the evening contained “mystic overtones” of a “quasi-religious” nature. Eva Perón has often been credited with organizing the rally of thousands that freed Juan Perón from prison on 17 October 1945.

After his release from prison, Juan Perón decided to campaign for the presidency of the nation, which he won in a landslide. Eva campaigned heavily for her husband during his 1946 presidential bid. Using her weekly radio show, she delivered powerful speeches with heavy populist rhetoric urging the poor to align themselves with Perón’s movement. Though she had become wealthy from her radio and modeling success, she highlighted her own humble upbringing as a way of showing solidarity with the impoverished classes.

For the political purpose, Eva went on the ‘Rainbow Tour’ of Europe in 1947. As part of this tour, she visited Spain, Rome, France, and Switzerland where she met with a number of important dignitaries and heads of state.

During her tour to Europe, Eva Perón was featured in a cover story for Time magazine. The cover’s caption “Eva Perón: Between two worlds, an Argentine rainbow” was a reference to the name given to Eva’s European tour, The Rainbow Tour. This was the only time in the periodical’s history that a South American first lady appeared alone on its cover.

In 1951, Eva appeared again with Juan Perón. However, the 1947 cover story was also the first publication to mention that Eva had been born out of wedlock. In retaliation, the periodical was banned from Argentina for several months.

Although she never held any government post, Eva acted as de facto minister of health and labor, awarding generous wage increases to the unions, who responded with political support for Perón. After cutting off government subsidies to the traditional Sociedad de Beneficencia (Spanish: “Aid Society”), thereby making more enemies among the traditional elite, she replaced it with her own Eva Perón Foundation, which was supported by “voluntary” union and business contributions plus a substantial cut of the national lottery and other funds. These resources were used to establish thousands of hospitals, schools, orphanages, homes for the aged, and other charitable institutions. Eva was largely responsible for the passage of the woman suffrage law and formed the Peronista Feminist Party in 1949. She also introduced compulsory religious education into all Argentine schools. In 1951, although dying of cancer, she obtained the nomination for vice president, but the army forced her to withdraw her candidacy.

The Sociedad de Beneficencia (Society of Beneficence), a charity group made up of 87 society ladies, was responsible for most works of charity in Buenos Aires prior to the election of Juan Perón. Fraser and Navarro write that at one point the Sociedad had been an enlightened institution, caring for orphans and homeless women, but that those days had long since passed by the time of the first term of Juan Perón. In the 1800s, the Sociedad had been supported by private contributions, largely those of the husbands of the society ladies. But by the 1940s, the Sociedad was supported by the government.

Because Eva came from a lower-class background, she identified with the members of the working classes and was strongly committed to improving their lives. She devoted several hours every day to meeting with poor people and visiting hospitals, orphanages, and factories. She also supervised the newly created Ministry of Health, which built many new hospitals and established a successful program to fight different diseases.

A large part of Eva’s work with the poor was carried out by the María Eva Duarte de Perón Welfare Foundation, established in June 1947. Its funds came from contributions, often obtained with force, from trade unions, businesses, and industrial firms. The foundation grew into an enormous semiofficial welfare agency that distributed food, clothing, medicine, and money to needy people throughout Argentina and on occasion to those suffering from disasters in other Latin American countries.

Within a few years, the foundation had assets in cash and goods in excess of three billion pesos, or over $200 million at the exchange rate of the late 1940s. It employed 14,000 workers, of whom 6,000 were construction workers and 26 were priests. It purchased and distributed annually 400,000 pairs of shoes, 500,000 sewing machines, and 200,000 cooking pots. The foundation also gave scholarships, built homes, hospitals, and other charitable institutions. Every aspect of the foundation was under Evita’s supervision. The foundation also built entire communities, such as Evita City, which still exists today. Due to the works and health services of the foundation, for the first time in history, there was no inequality in Argentine health care.

Enjoying great popularity among the descamisados, Eva Perón helped greatly in maintaining the loyalty of the masses to the Perón administration. On the other hand, her program of social welfare and her campaign for female suffrage led to considerable opposition among the gente bien (upper class), to whom Eva was unacceptable because of her humble background and earlier activities. Eva was driven by the desire to master those members of the government that had rejected her, and she could be cruel and spiteful with her enemies.

A new women’s suffrage bill was introduced, which the Senate of Argentina sanctioned on 21 August 1946. It was necessary to wait more than a year before the House of Representatives sanctioned it on 9 September 1947. Law 13,010 established the equality of political rights between men and women and universal suffrage in Argentina. Finally, Law 13,010 was approved unanimously. In a public celebration and ceremony, however, Juan Perón signed the law granting women the right to vote, and then he handed the bill to Eva, symbolically making it hers.

In June 1951 it was announced that Eva would be the vice presidential candidate on the reelection ticket with Perón in the upcoming national election. Eva’s candidacy was strongly supported by the General Confederation of Labor, but opposition within the military and her own failing health caused her to decline the nomination.

On 4 June 1952, Evita rode with Juan Perón in a parade through Buenos Aires in celebration of his re-election as President of Argentina. Evita was by this point so ill that she was unable to stand without support. Underneath her oversized fur coat was a frame made of plaster and wire that allowed her to stand. She took a triple dose of pain medication before the parade and took another two doses when she returned home.

In a ceremony a few days after Juan Perón’s second inauguration, Evita was given the official title of “Spiritual Leader of the Nation.”

Awards and Honor

Eva Peron appears on the 100 peso note first issued in 2012 and scheduled for replacement sometime in 2018.

Death and Legacy

Eva was suffering from cervical cancer for which she went through several surgeries. She died on July 26, 1952, at the age of thirty-two. Radio broadcasts throughout the country were interrupted with the announcement that “the Press Secretary’s Office of the Presidency of the Nation fulfills its very sad duty to inform the people of the Republic that at 20:25 hours, Mrs. Eva Perón, Spiritual Leader of the Nation, died.” Ordinary activities ceased; movies were stopped and patrons were asked to leave restaurants.

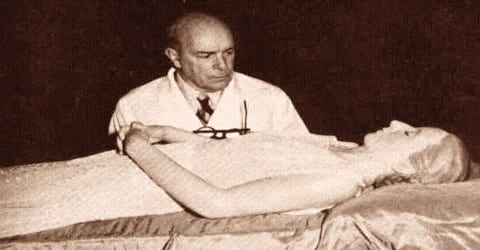

(Dr. Ara inspects Eva Perón’s embalmed corpse)

The morning after her death, while Evita’s body was being moved to the Ministry of Labour Building, eight people were crushed to death in the throngs. In the following 24 hours, over 2,000 people were treated in city hospitals for injuries sustained in the rush to be near Evita as her body was being transported, and thousands more would be treated on the spot. For the following two weeks, lines would stretch for many city blocks with mourners waiting hours to see Evita’s body lie in state at the Ministry of Labour.

After Eva’s death, which produced a huge display of public grief, Perón’s political fortunes began to decline. He was finally removed from office by a military takeover in September 1955.

Shortly after Evita’s death Pedro Ara, who was well known for his embalming skill, was approached to embalm the body. Biographer Fraser and Navarro write that it is doubtful that Evita ever expressed a wish to be embalmed, and suggest that it was most likely Juan Perón’s decision. Ara replaced the subject’s blood with glycerine in order to preserve the organs and lend an appearance of “artistically rendered sleep.”

In 1971, the military revealed that Evita’s body was buried in a crypt in Milan, Italy, under the name “María Maggi.” It appeared that her body had been damaged during its transport and storage, such as compressions to her face and disfigurement of one of her feet due to the body having been left in an upright position.

After her death in 1952, Eva remained a formidable influence in Argentine politics. Her working-class followers tried unsuccessfully to have her canonized, and her enemies, in an effort to exorcise her as a national symbol of Peronism, stole her embalmed body in 1955, after Juan Perón was overthrown, and secreted it in Italy for 16 years. In 1971 the military government, bowing to Peronist demands, turned over her remains to her exiled widower in Madrid. After Juan Perón died in office in 1974, his third wife, Isabel Perón, hoping to gain favor among the populace, repatriated the remains and installed them next to the deceased leader in a crypt in the presidential palace. Two years later a new military junta hostile to Peronism removed the bodies. Eva’s remains were finally interred in the Duarte family crypt in Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

Perón died in office in 1974. His third wife, Isabel Perón, whom he had married on 15 November 1961, and who had been elected vice-president, succeeded him. She became the first female president in the Western Hemisphere. Isabel had Eva Perón’s body returned to Argentina and (briefly) displayed beside her husband’s. Perón’s body was later buried in the Duarte family tomb in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires. The previous removal of Evita’s body was avenged by the Montoneros when they in 1970 stole the corpse of Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, whom they had previously killed. Montoneros then used the captive body of Aramburu to pressure for the repatriation of Evita’s body. Once Evita’s body arrived in Argentina, the Montoneros gave up Aramburu’s corpse and abandoned it in a street in Buenos Aires.

(Perón rests in the Recoleta Cemetery)

The Argentine government took elaborate measures to make Perón’s tomb secure. The tomb’s marble floor has a trapdoor that leads to a compartment containing two coffins. Under that compartment is a second trapdoor and a second compartment. That is where Perón’s coffin rests. Biographers Marysa Navarro and Nicholas Fraser write that the claim is often made that her tomb is so secure that it could withstand a nuclear attack. “It reflects a fear”, they write, “a fear that the body will disappear from the tomb and that the woman, or rather the myth of the woman, will reappear.”

Eva Perón’s friends and enemies agreed that she was a woman of great personal charm. Her supporters have elevated her to popular sainthood as the champion of the lower classes. The favorable portrayal of her in the play Evita first staged in 1978, and in the 1997 film of the same name, brought Eva to the forefront of the American public. By a large part of the officer corps of the military, however, she is greatly despised. There is still considerable difference of opinion regarding her true role in the Perón administration and her true place in Argentine history.

Information Source: