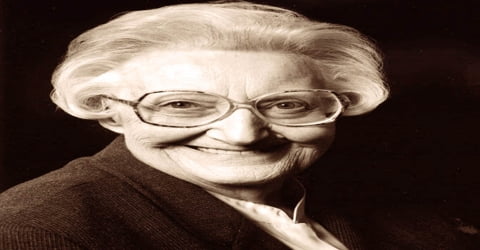

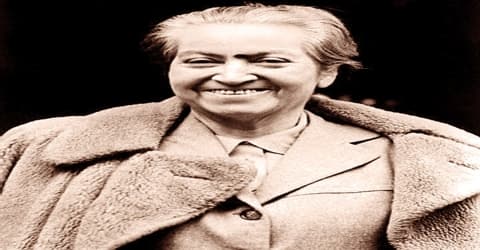

Biography of Gabriela Mistral

Gabriela Mistral – Chilean poet-diplomat, educator and humanist.

Name: Lucila Godoy Alcayaga

Date of Birth: 7 April 1889

Place of Birth: Vicuña, Chile

Date of Death: 10 January 1957 (aged 67)

Place of Death: Hempstead, New York

Occupation: Educator, Diplomat, Poet.

Father: Juan Gerónimo Godoy Villanueva

Mother: Petronila Alcayaga

Early Life

Gabriela Mistral, one of the most well-known Latin-American poets of the twentieth century, was born April 7, 1889, Vicuña, Chile. She was a woman with a multi-faceted personality she was a poet, an educator, a diplomat and a feminist all rolled into one.

Of Spanish, Basque, and Indian descent, Mistral grew up in a village of northern Chile and became a schoolteacher at age 15, advancing later to the rank of college professor. Throughout her life she combined writing with a career as an educator, cultural minister, and diplomat; her diplomatic assignments included posts in Madrid, Lisbon, Genoa, and Nice.

While working as an educator, she also started to write poetry, some of which were published in the local and national newspapers and magazines. The tragic death of her lover in 1909 influenced her to write Sonetos de la muerte which went on to win a national award for her when published years later. Her growing popularity as a poet also opened up newer avenues for her career growth as a teacher. She got many opportunities to teach at prestigious schools, and then gradually went on to become a college educator. Her rising stature in the international scenario made it impossible for her to remain in Chile for long.

Some central themes in her poems are nature, betrayal, love, a mother’s love, sorrow and recovery, travel, and Latin American identity as formed from a mixture of Native American and European influences. Her portrait also appears on the 5,000 Chilean peso banknote.

In the mid-1920’s, she represented Latin America in the Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations. She lived primarily in France and Italy between1926 and 1932. During this period, she also extensively toured many countries like Brazil, Argentina, the Caribbean, Uruguay, etc. She held a visiting professorship at Barnard College of Columbia University, worked briefly at Middlebury College and Vassar College. She published many articles in newspapers and magazines throughout the Spanish-speaking world.

In 1945 she became the first Latin American author to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature, “for her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world”.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Gabriela Mistral, pseudonym of Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, was born April 7, 1889, Vicuña, Chile. Her mother was of Basque descent while her father was a school teacher of Indian and Jewish descent. She also had one step-sister named Emelina who was fifteen years older to her. She grew up in a world of poverty after her father abandoned his family leaving his wife and daughters to fend for themselves. She had begun to get her poems published in local newspapers from an early age.

By age fifteen, she was supporting herself and her mother, Petronila Alcayaga, a seamstress, by working as a teacher’s aide in the seaside town of Compañia Baja, near La Serena, Chile.

Personal Life

In 1906, Mistral met Romelio Ureta, her first love, who killed himself in 1909. Shortly after, her second love married someone else. This heartbreak was reflected in her early poetry and earned Mistral her first recognized literary work in 1914 with Sonnets on Death (Sonnets de la muerte).

She never married but had a very profound love for children. She was a deeply spiritual person.

Mistral has a school named after her in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Career and Works

Gabriela Minstral began her career as a teacher’s aide at the age of fifteen. In spite of her lack of a solid foundation in formal education, her sister helped her to get a teaching job.

In 1904 Mistral published some early poems, such as Ensoñaciones (“Dreams”), Carta Íntima (“Intimate Letter”) and Junto al Mar (“By the Sea”), in the local newspaper El Coquimbo: Diario Radical, and La Voz de Elqui using a range of pseudonyms and variations on her civil name.

Mistral’s themes are repeated and unvaried throughout her work, but perhaps this continuity adds to the distinction and originality of her work. Mistral’s attention to the theme of love, which resembles the same theme in the love poems of Neruda, appears in “Sonetos de la muerte” in 1914, a collection of love poems remembering the dead that spread her fame throughout Latin America. In 1922, Mistral published her first notable collection of poems, Desolación, including “Dolor,” detailing the suicide of her former lover and plainly stating the theme of suffering which appears consistently in her work. Another work entitled Ternura (1924) reflects the repercussions of her lover’s death and her failure to marry by incorporating the themes of maternal sentiments and tenderness toward childhood. The theme of maternity further develeops in Mistral’s collection of poems entitled Tala, published in 1938. Although her 1954 work Lagar entails broader themes surrounding the existence of humanity, most of her work focuses on a continued attention to death and the impoverished, as well as a nostalgic appreciation for childhood and maternal emotions.

A member of the cultural committee of the League of Nations and Chilean consul to Madrid, Lisbon, Nice, and Naples, Mistral combined her educational ministry with her poetic talent to influence those she visited. In 1922 she was able to further her influence in Mexico, where upon the invitation of Jose Vasconcelos, she helped enhance the Mexican government’s attempts at educational reform.

She had been using the pen name Gabriela Mistral since June 1908 for much of her writing. After winning the Juegos Florales she infrequently used her given name of Lucila Godoy for her publications. She formed her pseudonym from the names of two of her favorite poets, Gabriele D’Annunzio, and Frédéric Mistral or, as another story has it, from a composite of the Archangel Gabriel and the mistral wind of Provence.

Her reputation as a poet was established in 1914 when she won a Chilean prize for three “Sonetos de la muerte” (“Sonnets of Death”). They were signed with the name by which she has since been known, which she coined from those of two of her favorite poets, Gabriele D’Annunzio, and Frédéric Mistral. A collection of her early works, Desolación (1922; “Desolation”), includes the poem “Dolor,” detailing the aftermath of a love affair that was ended by the suicide of her lover. Because of this tragedy, she never married, and a haunting, wistful strain of thwarted maternal tenderness informs her work. Ternura (1924, enlarged 1945; “Tenderness”), Tala (1938; “Destruction”), and Lagar (1954; “The Wine Press”) evidence a broader interest in humanity, but love of children and of the downtrodden remained her principal themes.

Between the years 1906 and 1912 she had taught, successively, in three schools near La Serena, then in Barrancas, then Traiguén in 1910, and in Antofagasta in the desert north, in 1911. By 1912 she had moved to work in a liceo, or high school, in Los Andes, where she stayed for six years and often visited Santiago. In 1918 Pedro Aguirre Cerda, then Minister of Education and a future president of Chile, promoted her appointment to direct a liceo in Punta Arenas. She moved on to Temuco in 1920, then to Santiago, where in 1921, she defeated a candidate connected with the Radical Party, Josefina Dey del Castillo, to be named the director of Santiago’s Liceo #6, the country’s newest and most prestigious girls’ school.

Her growing popularity as a poet also helped her in rising from one position to another. She got the opportunity to teach in a number of schools in various Chilean cities. The government of her country awarded her the title “Teacher of the Nation” in 1923.

As she became increasingly famous for her works in the fields of education and poetry, she received many invitations to attend conferences and make speeches.

Perhaps Mistral’s passionate tone is the characteristic that best defines her style and expresses her themes and purposes as a poet. Mistral places less emphasis on appealing to academic interests and instead invokes sentimental emotions in her readers. With an almost obsessive approach, Mistral’s personal tone painstakingly selected words and passionate voice expose her feelings of suffering and maternal longing.

In mid-1925 she was invited to represent Latin America in the newly formed Institute for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations. With her relocation to France in early 1926, she was effectively an exile for the rest of her life. She made a living, at first, from journalism and then giving lectures in the United States and in Latin America, including Puerto Rico. She variously toured the Caribbean, Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, among other places.

Mistral lived primarily in France and Italy between 1926 and 1932. During these years she worked for the League for Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations, attending conferences of women and educators throughout Europe and occasionally in the Americas. She held a visiting professorship at Barnard College of Columbia University in 1930–1931, worked briefly at Middlebury College and Vassar College in 1931 and was warmly received at the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras, where she variously gave conferences or wrote, in 1931, 1932, and 1933.

Mistral’s extraordinarily passionate verse, which is frequently colored by figures and words peculiarly her own, is marked by the warmth of feeling and emotional power. Selections of her poetry have been translated into English by the American writer Langston Hughes (1957; reissued 1972), by Mistral’s secretary and companion Doris Dana (1957; reissued 1971), by American writer Ursula K. Le Guin (2003), and by Paul Burns and Salvador Ortiz-Carboneres (2005). A Gabriela Mistral Reader (1993; reissued in 1997) was translated by Maria Giachetti and edited by Marjorie Agosín. Selected Prose and Prose-Poems (2002) was translated by Stephen Tapscott.

She published hundreds of articles in magazines and newspapers throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Among her confidants were Eduardo Santos, President of Colombia, all of the elected Presidents of Chile from 1922 to her death in 1957, Eduardo Frei Montalva, who would be elected president in 1964, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Her second major volume of poetry, Tala, appeared in 1938, published in Buenos Aires with the help of longtime friend and correspondent Victoria Ocampo. The proceeds for the sale were devoted to children orphaned by the Spanish Civil War. This volume includes many poems celebrating the customs and folklore of Latin America as well as Mediterranean Europe. Mistral uniquely fuses these locales and concerns, a reflection of her identification as “una mestiza de Vasco,” her European Basque-Indigenous Amerindian background.

Some of Mistral’s best-known poems include Piececitos de Niño, Balada, Todas Íbamos a ser Reinas, La Oración de la Maestra, El Ángel Guardián, Decálogo del Artista and La Flor del Aire. She wrote and published some 800 essays in magazines and newspapers; she was also a well-known correspondent and highly regarded orator both in person and over the radio.

Mistral may be most widely quoted in English for Su Nombre es Hoy (His Name is Today):

“We are guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, his blood is being made, and his senses are being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘Tomorrow,’ his name is today.”

Education and reform were constant focuses of Mistral throughout her life, and it is quite possible that through her travels and exposure as an educator, her poetry became well known and valued by those with whom she came in contact. Having lived through two world wars, Gabriela Mistral’s poetry occasionally slipped through the cracks of the cultural realm while the rest of the world paid more attention to political issues and literary works. This fact may have influenced the long-term popularity of Mistral’s work, but her poetry remains full of emotion and sentiment, portraying her thoughts about suffering, love, and nostalgia in a distinct and passionately intimate manner.

Awards and Honor

In 1914, Mistral was awarded the first prize in the Juegos Florales a national literary contest for her work Sonetos de la Muerte.

In 1945, she was honored with the Nobel Prize in Literature “for her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world”.

She received the Chilean National Prize in literature in 1951.

Her portrait appears on the 5,000 Chilean peso banknote.

Death and Legacy

During the last years of her life she made her home in the town of Roslyn, New York; in early January 1957, she transferred to Hempstead, New York, where she died from pancreatic cancer on 10 January 1957, aged 67. Her remains were returned to Chile nine days later. The Chilean government declared three days of national mourning, and hundreds of thousands of mourners came to pay her their respects.

Mistral’s work is characterized by including gray tones in her literature, sadness and bitterness are recurrent feelings on it. These are evoked in her writings as the reflection of a hard childhood which was plagued by deprivation coupled with a lack of affection in her home. However, Gabriela Mistral also shows through in her writings a great affection for children, since in her youth she became a teacher in a rural school. Religion was also reflected in her literature as it had a great influence on Catholicism in her life, however, she always reflected a more neutral stance regarding the conception of religion, so we can find in their literature gray tones combined with feelings of love and piety, making her into one of the worthiest representatives of Latin American literature of the twentieth century.

Information Source: