Biography of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte – French statesman and military leader.

Name: Napoleon Bonaparte

Date of Birth: 15 August 1769

Place of Birth: Ajaccio, Corsica, France

Date of Death: 5 May 1821 (aged 51)

Place of Death: Longwood, Saint Helena, UK

Father: Carlo Buonaparte

Mother: Letizia Ramolino

Spouse: Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma (m. 1810–1821), Empress Joséphine (m. 1796–1809)

Early Life

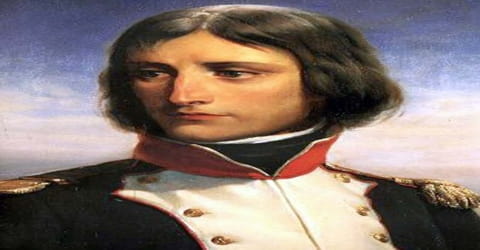

Napoleon Bonaparte, a French emperor, was born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, France. He was a French statesman and military leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the French Revolutionary Wars. He was Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814 and again briefly in 1815 during the Hundred Days.

Napoleon dominated European and global affairs for more than a decade while leading France against a series of coalitions in the Napoleonic Wars. He won most of these wars and the vast majority of his battles, building a large empire that ruled over continental Europe before its final collapse in 1815. He is considered one of the greatest commanders in history, and his wars and campaigns are studied at military schools worldwide. Napoleon’s political and cultural legacy has endured as one of the most celebrated and controversial leaders in human history.

He revolutionized military organization and training; sponsored the Napoleonic Code, the prototype of later civil-law codes; reorganized education; and established the long-lived Concordat with the papacy.

He was born Napoleone di Buonaparte (Italian: [napoleˈoːne di ˌbwɔnaˈparte]) in Corsica to a relatively modest family of Italian origin from the minor nobility. He was serving as an artillery officer in the French army when the French Revolution erupted in 1789. He rapidly rose through the ranks of the military, seizing the new opportunities presented by the Revolution and becoming a general at age 24. The French Directory eventually gave him command of the Army of Italy after he suppressed a revolt against the government from royalist insurgents. At age 26, he began his first military campaign against the Austrians and the Italian monarchs aligned with the Habsburgs winning virtually every battle, conquering the Italian Peninsula in a year while establishing “sister republics” with local support, and becoming a war hero in France. In 1798, he led a military expedition to Egypt that served as a springboard to political power. He orchestrated a coup in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic.

By 1785 Napoleon was a second lieutenant in the French army, but he often returned to Corsica. In 1792 he took part in a power struggle between forces supporting Pasquale Paoli (1725–1807), a leader in the fight for Corsican independence, and those supporting the French. After Paoli was victorious, he turned against Napoleon and the Bonaparte family, forcing them to flee back to France. Napoleon then turned his attention to a career in the army there. The French Revolution (1789–93), a movement to overthrow King Louis XVI (1754–1793) and establish a republic, had begun. Upon his return from Corsica in 1793, Napoleon made a name for himself and won a promotion by helping to defeat the British at Toulon and regain that territory for France.

Napoleon’s many reforms left a lasting mark on the institutions of France and of much of western Europe. But his driving passion was the military expansion of French dominion, and, though at his fall he left France little larger than it had been at the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, he was almost unanimously revered during his lifetime and until the end of the Second Empire under his nephew Napoleon III as one of history’s great heroes.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Napoleon I, French in full Napoléon Bonaparte, original Italian Napoleone Buonaparte, byname the Corsican or the Little Corporal, French byname Le Corse or Le Petit Caporal, was born on August 15, 1769, in the Corsican city of Ajaccio. He was the fourth of eleven children of Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Romolino. His father, a member of a noble Italian family, remained on good terms with the French when they took over control of Corsica.

Around the time of Napoleon’s birth, Corsica’s occupation by the French had drawn considerable local resistance. Carlo Buonaparte had at first supported the nationalists siding with their leader, Pasquale Paoli. But after Paoli was forced to flee the island, Carlo switched his allegiance to the French. After doing so he was appointed assessor of the judicial district of Ajaccio in 1771, a plush job that eventually enabled him to enroll his two sons, Joseph and Napoleon, in France’s College d’Autun.

Napoleon began his education at a boys’ school in Ajaccio. When he turned 9 years old, he moved to the French mainland and enrolled at a religious school in Autun in January 1779. In May, he transferred with a scholarship to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château. In his youth, he was an outspoken Corsican nationalist and supported the state’s independence from France. Like many Corsicans, Napoleon spoke and read Corsican (as his mother tongue) and Italian (as the official language of Corsica). He began learning French in school at around age 10. Although he became fluent in French, he spoke with a distinctive Corsican accent and never learned how to spell French correctly. He was routinely bullied by his peers for his accent, birthplace, short stature, mannerisms, and inability to speak French quickly.

Napoleon later transferred to the College of Brienne, another French military school. While at school in France, he was made fun of by the other students for his lower social standing and because he spoke Spanish and did not know French well. His small size earned him the nickname of the “Little Corporal.” Despite this teasing, Napoleon received an excellent education. When his father died, Napoleon led his household.

Back home Napoleon got behind the Corsican resistance to the French occupation, siding with his father’s former ally, Pasquale Paoli. But the two soon had a falling-out, and when a civil war in Corsica began in April 1793, Napoleon, now an enemy of Paoli, and his family relocated to France, where they assumed the French version of their name: Bonaparte. Napoleon’s return to France from Corsica began with a service with the French military, where he rejoined his regiment at Nice in June 1793.

Personal Life

(Josephine de Beauharnais, first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte)

Napoleon married Joséphine de Beauharnais, widow of General Alexandre de Beauharnais (guillotined during the Reign of Terror) and the mother of two children, on March 9, 1796, in a civil ceremony. Joséphine was unable to give him a son. So in 1810, Napoleon arranged for the annulment of their marriage that he could wed Marie-Louise, the 18-year-old daughter of the emperor of Austria. The couple had a son, Napoleon II (a.k.a. the King of Rome) on March 20, 1811.

(Napoleon’s second wife, Marie-Louise)

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary, daughter of François Clary. Désirée’s sister Julie Clary had married Bonaparte’s elder brother Joseph.

Career and Works

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte has commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment. He served in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789 and took nearly two years’ leave in Corsica and Paris during this period. At this time, he was a fervent Corsican nationalist, and wrote to Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli in May 1789, “As the nation was perishing I was born. Thirty thousand Frenchmen were vomited on to our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood. Such was the odious sight which was the first to strike me”.

After being imprisoned for ten days on suspicion of treason and refusing an assignment to lead the Army of the West, Napoleon was assigned to work for the map department of the French war office. His military career nearly ended, but when forces loyal to the king attempted to regain power in Paris in 1795, Napoleon was called in to stop the uprising. As a reward, he was appointed the commander of the Army of the Interior. Later that year Napoleon met Josephine de Beauharnais (1763–1814), and they were married in March 1796. Within a few days, Napoleon left Josephine in Paris and started his new command of the Army of Italy. Soon the French troops were winning battle after battle against the Italians and Austrians. Napoleon advanced on Vienna, Austria, and engineered the signing of a treaty that gave France control of Italy.

Napoleon spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. He was a supporter of the republican Jacobin movement, organizing clubs in Corsica, and was given command over a battalion of volunteers. He was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against French troops.

He came into conflict with Paoli, who had decided to split with France and sabotage the Corsican contribution to the Expédition de Sardaigne, by preventing a French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena. Bonaparte and his family fled to the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.

The turmoil of the French Revolution created opportunities for ambitious military leaders like Napoleon. The young leader quickly showed his support for the Jacobins, a far-left political movement and the most well-known and popular political club from the French Revolution.

In 1792, three years after the Revolution had begun, France has declared a republic; the following year, King Louis XVI was executed. Ultimately, these acts led to the rise of Maximilien de Robespierre and what became, essentially, the dictatorship of the Committee of Public Safety. The years of 1793 and 1794 came to be known as the Reign of Terror, in which many as 40,000 people were killed. Eventually, the Jacobins fell from power and Robespierre was executed. In 1795 the Directory took control of the country, a power it would it assume until 1799.

Napoleon returned to Paris a hero, and he soon decided to invade Egypt. He sailed from Toulon, France, in May 1798 with an army of thirty-five thousand men. With only a few losses, all of lower Egypt came under Napoleon’s control. He set about reorganizing the government, the postal service, and the system for collecting taxes. He also helped build new hospitals for the poor. However, at this time a group of countries had banded together to oppose France. Austrian and Russian forces had regained control of almost all of Italy. Then, in August 1798, the British destroyed French ships in the Battle of the Nile, leaving the French army cut off from its homeland. Napoleon left the army under the command of General Jean Kléber and returned to France with a handful of officers.

In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west central France on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general for which the army already had a full quota and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.

Bonaparte was still in Paris in October 1795 when the National Convention, on the eve of its dispersal, submitted the new constitution of the year III of the First Republic to a referendum, together with decrees according to which two-thirds of the members of the National Convention were to be reelected to the new legislative assemblies. The royalists, hoping that they would soon be able to restore the monarchy, instigated a revolt in Paris to prevent these measures from being put into effect. Paul Barras, who had been entrusted with dictatorial powers by the National Convention, was unwilling to rely on the commander of the troops of the interior; instead, knowing of Bonaparte’s services at Toulon, he appointed him second in command. Thus, it was Napoleon who shot down the columns of rebels marching against the National Convention (13 Vendémiaire year IV; October 5, 1795), thereby saving the National Convention and the republic.

After falling out of favor with Robespierre, Napoleon came into the good graces of the Directory in 1795 after he saved the government from counter-revolutionary forces. For his efforts, Napoleon was soon named commander of the Army of the Interior. In addition, he was a trusted advisor to the Directory on military matters.

He ordered a young cavalry officer named Joachim Murat to seize large cannons and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795 Vendémiaire An IV in the French Republican Calendar; 1,400 royalists died and the rest fled. He had cleared the streets with “a whiff of grapeshot”, according to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.

In 1796, Napoleon took the helm of the Army of Italy, a post he’d been coveting. The army, just 30,000 strong, disgruntled and underfed, was soon turned around by the young military commander. Under his direction the rebuilt army won numerous crucial victories against the Austrians, greatly expanded the French empire and squashed an internal threat by the royalists, who wished to return France to a monarchy. All of this helped make Napoleon the military’s brightest star.

Arriving at his headquarters in Nice, Bonaparte found that his army, which on paper consisted of 43,000 men, numbered scarcely 30,000 ill-fed, ill-paid, and ill-equipped men. On March 28, 1796, he made his first proclamation to his troops:

Soldiers, you are naked, badly fed.…Rich provinces and great towns will be in your power, and in them, you will find honor, glory, wealth. Soldiers of Italy, will you be wanting in courage and steadfastness?

In a series of rapid victories during the Montenotte Campaign, he knocked Piedmont out of the war in two weeks. The French then focused on the Austrians for the remainder of the war, the highlight of which became the protracted struggle for Mantua. The Austrians launched a series of offensives against the French to break the siege, but Napoleon defeated every relief effort, scoring victories at the battles of Castiglione, Bassano, Arcole, and Rivoli. The decisive French triumph at Rivoli in January 1797 led to the collapse of the Austrian position in Italy. At Rivoli, the Austrians lost up to 14,000 men while the French lost about 5,000.

In the first encounter between the two commanders, Napoleon pushed back his opponent and advanced deep into Austrian territory after winning at the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797. The Austrians were alarmed by the French thrust that reached all the way to Leoben, about 100 km from Vienna, and finally decided to sue for peace. The Treaty of Leoben, followed by the more comprehensive Treaty of Campo Formio, gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of independence. He also authorized the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark.

Landing at Fréjus, France, in October 1799, Napoleon went directly to Paris, where he helped overthrow the Directory, a five-man executive body that had replaced the king. Napoleon was named first consul, or head of the government, and he received almost unlimited powers. After Austria and England ignored his calls for peace, he led an army into Italy and defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Marengo (1800). This brought Italy back under French control. The Treaty of Amiens in March 1802 ended the war with England for the time being. Napoleon also restored harmony between the Roman Catholic Church and the French government. He improved conditions within France as well by, among other things, establishing the Bank of France, reorganizing education, and reforming France’s legal system with a new set of laws known as the Code Napoleon.

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France. The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned that he might become a dictator. All told, Napoleon’s forces extracted an estimated $45 million in funds from Italy during their campaign there, another $12 million in precious metals and jewels; atop that, his forces confiscated more than three-hundred priceless paintings and sculptures. Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau to Paris to lead a coup d’état and purge the royalists on 4 September—Coup of 18 Fructidor. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent on Bonaparte, who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Bonaparte returned to Paris in December as a hero. He met Talleyrand, France’s new Foreign Minister—who served in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.

On March 21, 1804, Napoleon instituted the Napoleonic Code, otherwise known as the French Civil Code, parts of which are still in use around the world today. The Napoleonic Code forbade privileges based on birth, allowed freedom of religion, and stated that government jobs must be given to the most qualified. The terms of the code are the main basis for many other countries’ civil codes in Europe and North America.

Under his direction, Napoleon turned his reforms to the country’s economy, legal system and education, and even the Church, as he reinstated Roman Catholicism as the state religion. He also negotiated a European peace, which lasted just three years before the start of the Napoleonic Wars. His reforms proved popular. In 1802 he was elected consul for life, and two years later he was proclaimed emperor of France.

By 1802 the popular Napoleon was given the position of the first consul for life, with the right to name his replacement. In 1804 he had his title changed to an emperor. War resumed after a new coalition was formed against France. In 1805 the British destroyed French naval power in the Battle of Trafalgar. Napoleon, however, was able to defeat Russia and Austria in the Battle of Austerlitz. In 1806 Napoleon’s forces destroyed the Prussian army; after the Russians came to the aid of Prussia and were defeated themselves, Alexander I (1777–1825) of Russia made peace at Tilsit in June 1807. Napoleon was now free to reorganize western and central Europe as he pleased. After Sweden was defeated in 1808 with Russia’s help, only England remained to oppose Napoleon.

On July 1, 1798, Napoleon and his army traveled to the Middle East to undermine Great Britain’s empire by occupying Egypt and disrupting English trade routes to India. His military campaign proved disastrous. On August 1, 1798, Admiral Horatio Nelson’s fleet decimated Napoleon’s forces in the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon’s image was greatly harmed by the loss, and in a show of newfound confidence against the commander, Britain, Austria, Russia, and Turkey formed a new coalition against France. In the spring of 1799, French armies were defeated in Italy, forcing France to give up much of the peninsula. In October, Napoleon returned to France.

Bonaparte imposed a dictatorship on France, but its true character was at first disguised by the constitution of the year VIII (4 Nivôse, year VIII; December 25, 1799), drawn up by Sieyès. This constitution did not guarantee the “rights of man” or make any mention of “liberty, equality, and fraternity,” but it did reassure the partisans of the Revolution by proclaiming the irrevocability of the sale of national property and by upholding the legislation against the émigrés. It gave immense powers to the first consul, leaving only a nominal role to his two colleagues. The first consul namely, Bonaparte was to appoint ministers, generals, civil servants, magistrates, and the members of the Council of State and even was to have an overwhelming influence in the choice of members for the three legislative assemblies, though their members were theoretically to be chosen by universal suffrage. Submitted to a plebiscite, the constitution won by an overwhelming majority in February 1800.

Napoleon’s coronation took place on 2 December 1804. Two separate crowns were brought for the ceremony: a golden laurel wreath recalling the Roman Empire and a replica of Charlemagne’s crown. Napoleon entered the ceremony wearing the laurel wreath and kept it on his head throughout the proceedings. For the official coronation, he raised the Charlemagne crown over his own head in a symbolic gesture, but never placed it on top because he was already wearing the golden wreath. Instead, he placed the crown on Josephine’s head, the event commemorated in the officially sanctioned painting by Jacques-Louis David. Napoleon was also crowned King of Italy, with the Iron Crown of Lombardy, at the Cathedral of Milan on 26 May 1805. He created eighteen Marshals of the Empire from among his top generals to secure the allegiance of the army on 18 May 1804, the official start of the Empire.

In March 1814 Paris fell to a coalition made up of Britain, Prussia, Sweden, and Austria. Napoleon stepped down in April. Louis XVIII (1755–1824), the brother of Louis XVI, was placed on the French throne. Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba, but after ten months he made plans to return to power. He landed in southern France in February 1815 with 1,050 soldiers and marched to Paris, where he reinstated himself to power. Louis XVIII fled, and Napoleon’s new reign began. The other European powers gathered to oppose him, and Napoleon was forced to return to war.

There was a lull in fighting over the winter of 1812–13 while both the Russians and the French rebuilt their forces; Napoleon was able to field 350,000 troops. Heartened by France’s loss in Russia, Prussia joined with Austria, Sweden, Russia, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal in a new coalition. Napoleon assumed command in Germany and inflicted a series of defeats on the Coalition culminating in the Battle of Dresden in August 1813. Despite these successes, the numbers continued to mount against Napoleon, and the French army was pinned down by a force twice its size and lost at the Battle of Leipzig. This was by far the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars and cost more than 90,000 casualties in total.

After Napoleon’s abdication from power in 1815, fearing a repeat of his earlier return from exile on Elba, the British government sent him to the remote island of St. Helena in the southern Atlantic. For the most part, Napoleon was free to do as he pleased at his new home. He had leisurely mornings, wrote often and read a lot. But the routine of life soon got to him, and he often shut himself indoors.

The Battle of Waterloo was over within a week. On June 18, 1815, the combined British and Prussian armies defeated Napoleon. He returned to Paris and stepped down for a second time on June 22. He had held power for exactly one hundred days. Napoleon at first planned to go to America, but he surrendered to the British on July 3. He was sent into exile on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. There he spent his remaining years until he died of cancer on May 5, 1821.

Death and Legacy

Napoleon’s personal physician, Barry O’Meara, warned London that his declining state of health was mainly caused by the harsh treatment. Napoleon confined himself for months on end in his damp and wretched habitation of Longwood.

(Napoleon on His Death Bed)

Napoleon died on May 5, 1821, on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. By 1817 Napoleon’s health had been deteriorating and he showed the early signs of a stomach ulcer or possibly cancer. In early 1821 he was bedridden and growing weaker by the day. In April of that year, he dictated his last will:

“I wish my ashes to rest on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of that French person which I have loved so much. I die before my time, killed by the English oligarchy and its hired assassins.”

(Bronze death mask of Napoleon I, modeled in 1821, cast in 1833)

Napoleon’s original death mask was created around 6 May, although it is not clear which doctor created it. In his will, he had asked to be buried on the banks of the Seine, but the British governor said he should be buried on Saint Helena, in the Valley of the Willows.

(Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides)

Napoleon’s tomb is located in Paris, France, in the Dôme des Invalides. Originally a royal chapel built between 1677 and 1706, the Invalides was turned into a military pantheon under Napoleon. In addition to Napoleon Bonaparte, several other French notables are buried there today, including Napoleon’s son, l’Aiglon, the King of Rome; his brothers, Joseph and Jérôme Bonaparte; Generals Bertrand and Duroc; and the French marshals Foch and Lyautey.

Information Source: