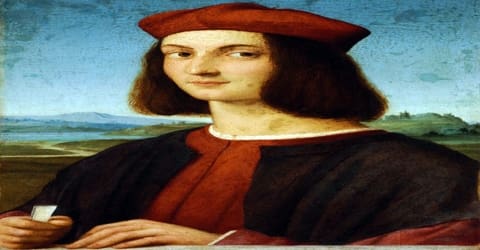

Biography of Raphael

Raphael – Italian painter and architect.

Name: Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino

Date of Birth: March 28 or April 6, 1483

Place of Birth: Urbino, Duchy of Urbino

Date of Death: April 6, 1520 (aged 37)

Place of Death: Rome, Papal States

Father: Giovanni Santi

Mother: Magia Di Battista Di Nicola Ciarla

Known for: Painting, Architecture

Early Life

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, known as Raphael was born on April 6, 1483, in Urbino, Italy. Raphael is best known for his “Madonnas,” including the Sistine Madonna, and for his large figure compositions in the Palace of the Vatican in Rome. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur. Together with Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, he forms the traditional trinity of great masters of that period.

Raphael was enormously productive, running an unusually large workshop and, despite his death at 37, leaving a large body of work. Many of his works are found in the Vatican Palace, where the frescoed Raphael Rooms were the central, and the largest, work of his career. The best-known work is The School of Athens in the Vatican Stanza Della Segnatura. After his early years in Rome, much of his work was executed by his workshop from his drawings, with considerable loss of quality. He was extremely influential in his lifetime, though outside Rome his work was mostly known from his collaborative printmaking.

Living in Florence from 1504 to 1507, he began painting a series of “Madonnas.” In Rome from 1509 to 1511, he painted the Stanza della Segnatura (“Room of the Signatura”) frescoes located in the Palace of the Vatican. He later painted another fresco cycle for the Vatican, in the Stanza d’Eliodoro (“Room of Heliodorus”). In 1514, Pope Julius II hired Raphael as his chief architect. Around the same time, he completed his last work in his series of the “Madonnas,” an oil painting called the Sistine Madonna.

After his death, the influence of his great rival Michelangelo was more widespread until the 18th and 19th centuries, when Raphael’s more serene and harmonious qualities were again regarded as the highest models. His career falls naturally into three phases and three styles, first described by Giorgio Vasari: his early years in Umbria, then a period of about four years (1504–1508) absorbing the artistic traditions of Florence, followed by his last hectic and triumphant twelve years in Rome, working for two Popes and their close associates.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Raphael, Italian in full Raffaello Sanzio or Raffaello Santi, was born on April 6, 1483, Urbino, Duchy of Urbino (Italy). Raphael was the son of Giovanni Santi and Magia di Battista Ciarla; his mother died in 1491. His father was, according to the 16th-century artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari, a painter “of no great merit.” He was, however, a man of culture who was in constant contact with the advanced artistic ideas current at the court of Urbino. He gave his son his first instruction in painting, and, before his death in 1494, when Raphael was 11, he had introduced the boy to humanistic philosophy at the court.

Raphael grew up in an artistically stimulating environment as his hometown was a center for literary culture.

(Giovanni Santi, Raphael’s father; Christ supported by two angels, c.1490)

His success in this role quickly surpassed his father’s; Raphael was soon considered one of the finest painters in town. As a teen, he was even commissioned to paint for the Church of San Nicola in the neighboring town of Castello.

His mother died in 1491 when he was just eight years old. His father subsequently remarried, but he too died in 1494. Young Raphael, though just 11 at that time, started helping his step-mother manage his late father’s workshop. He had started painting at an early age and received training from the likes of Pietro Perugino and Timoteo Viti. By the time he was in his teens, he had produced a remarkable self-portrait. He was fully trained by 1500.

Personal Life

He was rich and famous and lived a rather grand life. He never married though he had several lovers, including his long-term mistress, Margherita Luti. He was once engaged to Maria Bibbiena, Cardinal Medici Bibbiena’s niece, though the marriage never took place.

He is said to have had many affairs, but a permanent fixture in his life in Rome was “La Fornarina”, Margherita Luti, the daughter of a baker (fornaro) named Francesco Luti from Siena who lived at Via del Governo Vecchio. He was made a “Groom of the Chamber” of the Pope, which gave him status at court and an additional income, and also a knight of the Papal Order of the Golden Spur. Vasari claims he had toyed with the ambition of becoming a Cardinal, perhaps after some encouragement from Leo, which also may account for his delaying his marriage.

Career and Works

In 1500 a master painter named Pietro Vannunci, otherwise known as Perugino, invited Raphael to become his apprentice in Perugia, in the Umbria region of central Italy. In Perugia, Perugino was working on frescoes at the Collegio del Cambia. The apprenticeship lasted four years and provided Raphael with the opportunity to gain both knowledge and hands-on experience. During this period, Raphael developed his own unique painting style, as exhibited in the religious works the Mond Crucifixion (circa 1502), The Three Graces (circa 1503), The Knight’s Dream (1504) and the Oddi altarpiece, Marriage of the Virgin, completed in 1504.

In 1502 he went to Siena at the invitation of another pupil of Perugino, Pinturicchio, “being a friend of Raphael and knowing him to be a draughtsman of the highest quality” to help with the cartoons, and very likely the designs, for a fresco series in the Piccolomini Library in Siena Cathedral. He was evidently already much in demand even at this early stage in his career.

It is clear from this that Raphael had already given proof of his mastery, so much so that between 1501 and 1503 he received a rather important commission to paint the Coronation of the Virgin for the Oddi Chapel in the church of San Francesco, Perugia (and now in the Vatican). The great Umbrian master Pietro Perugino was executing the frescoes in the Collegio del Cambio at Perugia between 1498 and 1500, enabling Raphael, as a member of his workshop, to acquire extensive professional knowledge.

In 1504, Raphael left his apprenticeship with Perugino and moved to Florence, where he was heavily influenced by the works of the Italian painters Fra Bartolommeo, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Masaccio. To Raphael, these innovative artists had achieved a whole new level of depth in their composition. By closely studying the details of their work, Raphael managed to develop an even more intricate and expressive personal style that was evident in his earlier paintings.

As earlier with Perugino and others, Raphael was able to assimilate the influence of Florentine art, whilst keeping his own developing style. Frescos in Perugia of about 1505 show a new monumental quality in the figures which may represent the influence of Fra Bartolomeo, who Vasari says was a friend of Raphael. But the most striking influence in the work of these years is Leonardo da Vinci, who returned to the city from 1500 to 1506.

(Madonna of the Pinks, c. 1506–7, National Gallery, London)

From 1504 through 1507, Raphael produced a series of “Madonnas,” which extrapolated on Leonardo da Vinci’s works. Raphael’s experimentation with this theme culminated in 1507 with his painting, La belle jardinière. That same year, Raphael created his most ambitious work in Florence, the Entombment, which was evocative of the ideas that Michelangelo had recently expressed in his Battle of Cascina.

(The Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1506, using Leonardo’s pyramidal composition for subjects of the Holy Family.)

Another drawing is a portrait of a young woman that uses the three-quarter length pyramidal composition of the just-completed Mona Lisa but still looks completely Raphaelesque. Another of Leonardo’s compositional inventions, the pyramidal Holy Family, was repeated in a series of works that remain among his most famous easel paintings. There is a drawing by Raphael in the Royal Collection of Leonardo’s lost Leda and the Swan, from which he adapted the contrapposto pose of his own Saint Catherine of Alexandria. He also perfects his own version of Leonardo’s sfumato modeling, to give subtlety to his painting of flesh, and develops the interplay of glances between his groups, which are much less enigmatic than those of Leonardo. But he keeps the soft clear light of Perugino in his paintings.

In 1507 Raphael was commissioned to paint the Deposition of Christ. In this work, it is obvious that Raphael set himself deliberately to learn from Michelangelo the expressive possibilities of human anatomy. But Raphael differed from Leonardo and Michelangelo, who were both painters of dark intensity and excitement, in that he wished to develop a calmer and more-extroverted style that would serve as a popular, universally accessible form of visual communication.

(The Parnassus, 1511, Stanza della Segnatura)

He moved to Rome in 1508. The new Pope Julius II commissioned him to fresco, which was intended to become the Pope’s private library at the Vatican Palace. Several other artists were already working on different rooms of the library, and ‘The Stanza della segnatura’ (“Room of the Signatura”) was the first to be decorated by Raphael’s frescoes. The Stanza della Segnatura series of frescos include The Triumph of Religion and The School of Athens. In the fresco cycle, Raphael expressed the humanistic philosophy that he had learned in the Urbino court as a boy.

In the years to come, Raphael painted an additional fresco cycle for the Vatican, located in the Stanza d’Eliodoro (“Room of Heliodorus”), featuring The Expulsion of Heliodorus, The Miracle of Bolsena, The Repulse of Attila from Rome and The Liberation of Saint Peter. During this same time, the ambitious painter produced a successful series of “Madonna” paintings in his own art studio. The famed Madonna of the Chair and Sistine Madonna were among them.

(Raphael Sanzio (Italian: Raffaello) (1483 – 1520) Solly Madonna Oil on)

Raphael spent the last 12 years of his short life in Rome. They were years of feverish activity and successive masterpieces. His first task in the city was to paint a cycle of frescoes in a suite of medium-sized rooms in the Vatican papal apartments in which Julius himself lived and worked; these rooms are known simply as the Stanze. The Stanza della Segnatura (1508–11) and Stanza d’Eliodoro (1512–14) were decorated practically entirely by Raphael himself; the frescoes in the Stanza dell’Incendio (1514–17), though designed by Raphael, were largely executed by his numerous assistants and pupils.

By 1514, Raphael had achieved fame for his work at the Vatican and was able to hire a crew of assistants to help him finish painting frescoes in the Stanza dell’Incendio, freeing him up to focus on other projects. While Raphael continued to accept commissions — including portraits of popes Julius II and Leo X — and his largest painting on canvas, The Transfiguration (commissioned in 1517), he had by this time begun to work on architecture. After architect Donato Bramante died in 1514, the pope hired Raphael as his chief architect. Under this appointment, Raphael created the design for a chapel in Sant’ Eligio degli Orefici. He also designed Rome’s Santa Maria del Popolo Chapel and an area within Saint Peter’s new basilica.

Between 1512 and 1514 he painted ‘The Mass at Bolsena’. A self-portrait of Raphael as one of the Swiss Guards in the lower right of the fresco is present in the painting. One of his most famous paintings, ‘La donna velata’ (“The woman with the veil”), was completed in 1514–15. The painting portrays a beautiful young woman, traditionally identified as his Roman mistress, dressed in finery, depicting opulence.

(The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1515, one of the seven remaining Raphael Cartoons for tapestries for the Sistine Chapel.)

One of his most important papal commissions was the Raphael Cartoons (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum), a series of 10 cartoons, of which seven survive, for tapestries with scenes of the lives of Saint Paul and Saint Peter, for the Sistine Chapel. The cartoons were sent to Brussels to be woven in the workshop of Pier van Aelst. It is possible that Raphael saw the finished series before his death they were probably completed in 1520. He also designed and painted the Loggie at the Vatican, a long thin gallery then open to a courtyard on one side, decorated with Roman-style grottesche. He produced a number of significant altarpieces, including The Ecstasy of St. Cecilia and the Sistine Madonna.

He was commissioned by the Sicilian monastery of Santa Maria dello Spasimo in Palermo to paint ‘Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary’, a work which he completed in 1517. Also known as ‘Lo Spasimo’ or ‘Il Spasimo di Sicilia’, the painting is considered to be slightly controversial. He established a workshop and had around 50 pupils and assistants. He is credited to have run his workshop in the most efficient manner and several of his students became famous artists in their own right.

He was also a highly skilled architect who designed several buildings and was reputed to be one of the most important architects in Rome during the mid-1510s.

Raphael’s architectural work was not limited to religious buildings. It also extended to designing palaces. Raphael’s architecture honored the classical sensibilities of his predecessor, Donato Bramante, and incorporated his use of ornamental details. Such details would come to define the architectural style of the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods.

(Palazzo Branconio dell’Aquila, now destroyed)

An important building, the Palazzo Branconio dell’Aquila for Leo’s Papal Chamberlain Giovanni Battista Branconio, was completely destroyed to make way for Bernini’s piazza for St. Peter’s, but drawings of the façade and courtyard remain. The façade was an unusually richly decorated one for the period, including both painted panels on the top story (of three), and much sculpture on the middle one.

The main designs for the Villa Farnesina were not by Raphael, but he did design and decorated with mosaics, the Chigi Chapel for the same patron, Agostino Chigi, the Papal Treasurer. Another building, for Pope Leo’s doctor, the Palazzo di Jacobo da Brescia, was moved in the 1930s but survives; this was designed to complement a palace on the same street by Bramante, where Raphael himself lived for a time.

His last painting was ‘The Transfiguration’ in 1520. The painting stands as an allegory of the transformative nature of representation and exemplifies Raphael’s development as an artist.

Raphael painted several of his works on wood support (Madonna of the Pinks) but he also used canvas (Sistine Madonna) and he was known to employ drying oils such as linseed or walnut oils. His palette was rich and he used almost all of the then available pigments such as ultramarine, lead-tin-yellow, carmine, vermilion, madder lake, verdigris, and ochres. In several of his paintings (Ansidei Madonna), he even employed the rare brazilwood lake, metallic powdered gold and even less known metallic powdered bismuth.

Raphael was also a keen student of archaeology and of ancient Greco-Roman sculpture, echoes of which are apparent in his paintings of the human figure during the Roman period. In 1515 Leo X put him in charge of the supervision of the preservation of marbles bearing valuable Latin inscriptions; two years later he was appointed a commissioner of antiquities for the city, and he drew up an archaeological map of Rome. Raphael had by this time been put in charge of virtually all of the papacy’s various artistic projects in Rome, involving architecture, paintings and decoration, and the preservation of antiquities.

Raphael’s last masterpiece is the Transfiguration (commissioned by Giulio Cardinal de’ Medici in 1517), an enormous altarpiece that was unfinished at his death and completed by his assistant Giulio Romano.

Death and Legacy

(Raphael’s sarcophagus)

On April 6, 1520, Raphael’s 37th birthday, he died suddenly and unexpectedly of mysterious causes in Rome, Italy. He had been working on his largest painting on canvas, The Transfiguration (commissioned in 1517), at the time of his death. When his funeral mass was held at the Vatican, Raphael’s unfinished Transfiguration was placed on his coffin stand. Raphael’s body was interred at the Pantheon in Rome, Italy.

His funeral was extremely grand, attended by large crowds. The inscription in his marble sarcophagus, an elegiac distich written by Pietro Bembo, reads: “Ille hic est Raffael, timuit quo sospite Vinci, Rerum Magna parens et moriente mori”, meaning: “Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was dying, feared herself to die.”

Following his death, Raphael’s movement toward Mannerism influenced painting styles in Italy’s advancing Baroque period. Celebrated for the balanced and harmonious compositions of his “Madonnas,” portraits, frescoes, and architecture, Raphael continues to be widely regarded as the leading artistic figure of Italian High Renaissance classicism.

Information Source: