Biography of Samuel Morse

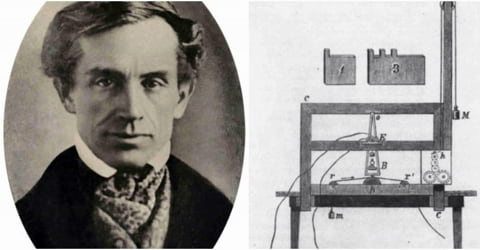

Samuel Morse – American painter and inventor.

Name: Samuel Finley Breese Morse

Date of Birth: April 27, 1791

Place of Birth: Charlestown, Massachusetts

Date of Death: April 2, 1872 (aged 80)

Place of Death: 5 West 22nd Street, New York City, New York

Father: Jedidiah Morse

Mother: Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese

Siblings: Richard Cary Morse, Sidney Edwards Morse

Spouse(s): Elizabeth Griswold (m. 1848–1872), Lucretia Walker (m. 1818–1825)

Children: Samuel Morse, William Morse, Edward Morse, Charles Morse, James Morse, Susan Morse, Cornelia Morse

Occupation: Painter, Inventor

Known for: The invention and transmission of Morse code

Early Life

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, USA. He was an American painter and inventor. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age, Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph system based on European telegraphs. He was a co-developer of the Morse code and helped to develop the commercial use of telegraphy.

Samuel Morse received his schooling as a boarder at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, from where, age 14, he proceeded to Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut in October 1805. From early childhood, he had drawn pictures for pleasure. Now he blossomed as an artist, helping fund his education by selling paintings. He did not charge his friends for portraits he painted of them.

Samuel took a job as a clerk in a Charlestown bookstore. During this time he continued to paint. His father reversed his decision and in 1811 allowed Morse to travel to England to pursue art. During this time, Morse worked at the Royal Academy with the respected American artist Benjamin West (1738–1820).

Born to a modest household, Morse started his career as a painter, his forte being portraiture. In no time, he established a name for himself in the field of painting and painted portraits of significant personalities such as former US President John Adams and James Monroe and French aristocrat Marquis de Lafayette. Though Morse was always fascinated with electromagnetism, it was the sudden news of the death of his wife that gave him the impetus to come up with a device that allowed long-distance communication. After years of hard work, he finally came up with the single-wire telegraph system that changed the way people sent and received messages in the world. He co-developed Morse Code, a method of transmitting textual information as a series on an off tones. Interestingly, in some parts of the world, Morse Code is still in use in radio communications

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, on April 27, 1791. He was the first son of Jedidiah Morse, a clergyman, and Elizabeth Breese, of New Jersey.

His father was a great preacher of the Calvinist faith and supporter of the American Federalist party. He thought it helped preserve Puritan traditions (strict observance of Sabbath, among other things), and believed in the Federalist support of an alliance with Britain and a strong central government. Morse strongly believed in education within a Federalist framework, alongside the installation of Calvinist virtues, morals, and prayers for his first son.

“Finley,” as his parents called him, was the son quickest to change moods while his other two brothers, Sidney and Richard, were less temperamental. His brothers helped him out many times in his adult years.

Morse gained his early education from Philips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts before enrolling at the Yale University to study religious philosophy, mathematics, and science of horses. While at Yale, he attended lectures on electricity from Benjamin Silliman and Jeremiah Day and was a member of the Society of Brothers in Unity.

While at Yale, he attended lectures on electricity. To support his living, he took to painting. In 1810, he graduated from Yale with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

His most notable early work includes ‘Landing of the Pilgrims’ which caught the attention of Washington Allston. Impressed by his work of art, he encouraged Morse to move to England.

Personal Life

Samuel Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. They had three children: Susan, Charles, and James. Lucretia died shortly after the birth of James in February 1825.

Morse married Sarah Elizabeth Griswold on August 10, 1848. They had four children: Samuel, Cornelia, William, and Edward.

Morse was a strong supporter of Protestant Christianity and a fierce opponent of Roman Catholicism. He campaigned to restrict the immigration of Catholics into America. He did not oppose slavery. A wealthy man, he donated large sums to causes he supported, such as the founding of Vasser College for women in 1861: he was a college trustee from 1861-1872. Morse also financially supported Yale College, Protestant churches and Bible societies, and struggling, artists.

Career and Works

Morse expressed some of his Calvinist beliefs in his painting, Landing of the Pilgrims, through the depiction of simple clothing as well as the people’s austere facial features. His image captured the psychology of the Federalists; Calvinists from England brought to North America ideas of religion and government, thus linking the two countries. This work attracted the attention of the notable artist, Washington Allston. Allston wanted Morse to accompany him to England to meet the artist Benjamin West. Allston arranged with Morse’s father a three-year stay for painting study in England. The two men set sail aboard Libya on July 15, 1811.

He perfected his painting technique so much so that by 1811, he gained admission at the Royal Academy. Taking inspiration from the works of Renaissance artists, Michelangelo and Raphael, he came up with his masterpiece, ‘Dying Hercules’ that gave an insight into his political view against British and American Federalists.

In 1815 Morse returned to America and set up a studio in Boston, Massachusetts. He soon discovered that his large canvases attracted attention but not sales. In those days Americans looked to painters primarily for portraits, and Morse found that even these sales were difficult to get. He traveled extensively in search of work, finally settling in New York City in 1823. Perhaps his two best-known canvases are his portraits of the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834; a French general who served with George Washington (1732–1799) during the American Revolution), which he painted in Washington, D.C., in 1825. In the United States, he received a commission to paint portraits of former Presidents, John Adams, and James Monroe. Additionally, he painted portraits of several wealthy merchants and important political figures.

Morse had moved to New Haven. His commissions for The House of Representatives (1821) and a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette (1825) engaged his sense of democratic nationalism. The House of Representatives was designed to capitalize on the success of François Marius Granet’s The Capuchin Chapel in Rome, which toured the United States extensively throughout the 1820s, attracting audiences willing to pay the 25-cent admission fee.

In 1826 Morse helped found and became the first president of, the National Academy of Design, an organization that was intended to help secure sales for artists and to raises the taste of the public. The previous year Morse’s wife had died; in 1826 his father died. The death of his mother in 1828 dealt another severe blow, and the following year Morse left for Europe to recover.

In 1826, he helped found the National Academy of Design in New York City. He served as the Academy’s President from 1826 to 1845 and again from 1861 to 1862.

(The Chapel of the Virgin at Subiaco, 1830.)

From 1830 to 1832, Morse traveled and studied in Europe to improve his painting skills, visiting Italy, Switzerland, and France. During his time in Paris, he developed a friendship with the writer James Fennimore Cooper. As a project, he painted miniature copies of 38 of the Louvre’s famous paintings on a single canvas (6 ft. x 9 ft), which he entitled The Gallery of the Louvre. He completed the work upon his return to the United States.

In 1832, returning from a trip to Europe, Morse met Charles Thomas Jackson, who demonstrated an electromagnet to him. This was when Morse, ever mindful of arriving back in New Haven to find his wife already buried, first had the idea for a telegraph.

On the voyage, he met Charles Thomas Jackson, an eccentric doctor, and inventor, with whom he discussed electromagnetism. Jackson assured Morse that an electric impulse could be carried along even a very long wire. Morse later recalled that he reacted to this news with the thought that “if this be so, and the presence of electricity can be made visible in any desired part of the circuit, I see no reason why intelligence might not be instantaneously transmitted by electricity to any distance.” He immediately made some sketches of a device to accomplish this purpose.

Morse quit painting and turned his attention solely to electromagnetism. In 1835, he designed his first telegraph and submitted the findings at the US Patent Office. Morse was facing difficulty getting a telegraphic signal to carry over more than a few hundred yards of wire.

On January 11, 1838, he along with his partners made a first public demonstration of the electric telegraph, in Morristown, New Jersey. The first public transmission message was, ‘A patient waiter is no loser’.

Morse moved to Washington DC to avail federal sponsorship to make the telegraph line a viable technology but he met little success. After much wandering, Morse finally gained financial support. On a subsequent visit to Paris in 1839, Morse met Louis Daguerre. He became interested in the latter’s daguerreotype the first practical means of photography. Morse wrote a letter to the New York Observer describing the invention, which was published widely in the American press and provided a broad awareness of the new technology.

Some of Morse’s paintings and sculptures are on display at his Locust Grove estate in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Even as an art professor at the University of the City of New York, the telegraph was never far from Morse’s mind. In September 1837 Morse formed a partnership with Alfred Vail, who contributed both money and mechanical skill. In 1838, with the help of Gale and Alfred Vail, Morse devised and introduced more sophisticated relays at frequent intervals in a wireline and sent a message ten miles (16 km). For several years, Morse was unable to get funding to scale up his system. However, in 1843, Congress finally approved $30,000 to build a 38-mile (61 km) telegraph line along the railroad between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore.

On May 24, 1844, Morse sent the message, “What hath God wrought,” from Washington to Baltimore. His system could transmit thirty characters a minute. Within six years, the United States had 12,000 miles (19,000 km) of telegraph lines in operation.

In 1847, Morse finally received the patent for his telegraph. Two years later, he was elected as an Associate Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1851, his telegraphic line was adopted as the standard line for European telegraphy.

Morse Code – In order to send messages along the wire, Morse devised a code in which each letter in the alphabet was represented by a particular number of electrical clicks. The codes were sent as electrical pulses of different lengths. The code was improved by Morse’s assistant and financial backer Alfred Vail. Morse wanted his telegraph system to deliver a permanent message. It did so in the form of permanent indentations dots and dashes on a paper tape.

In 1858, Morse was paid a sum of 400,000 French francs by the governments of France, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, Piedmont, Russia, Sweden, Tuscany, and Turkey. The same year, he was also elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

He offered support to Cyrus West Field’s plans of setting up a transoceanic telegraph line and even invested $10,000. After much ado, the first transatlantic telegraph message was sent in 1858.

Morse was willing to sell all of his rights to the invention to the federal government for one hundred thousand dollars, but a combination of a lack of congressional interest and the presence of private greed frustrated the plan. Instead, he turned his business affairs over to Amos Kendall. Morse then settled down to a life of wealth and fame. He was generous in his charitable gifts and was one of the founders of Vassar College in 1861. His last years were spoiled; however, by questions as to how much he had been helped by others, especially Joseph Henry.

Morse retired from public life in an ostentatious manner. A day-long celebration which included the unveiling of his statue in New York’s Central Park was followed with a grand finale at the NY Academy of Music where he transmitted his last official message.

During the last months of his life, he indulged in a lot of philanthropic works, giving large sums to charitable institutions. He started to take interest in the relationship of science and religion.

Awards and Honor

Morse was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1815.

Sultan Ahmad I ibn Mustafa of Turkey inducted him into the Order of Glory, Emperor of Austria presented him Great Golden Medal of Science and Arts and Emperor of France bestowed upon him a cross of Chevalier in the Légiond’honneur.

While the King of Denmark credited him with the Cross of a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog, the Queen of Spain presented him with the honor of Cross of Knight Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic. Other significant awards include Order of the Tower and Sword from the kingdom of Portugal and Chevalier of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus by Italy.

A blue plaque was erected to commemorate him at 141 Cleveland Street, London, where he lived from 1812 to 1815.

The government of United States did not recognize him until the last years of his life. He lived to see a statue of himself unveiled at the New York Central Park. Posthumously, his portrait was engraved in the United States two-dollar bill silver certificate series in 1896.

In 1975, Morse was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Death and Legacy

Samuel Morse died, age 80, in New York City on April 2, 1872. He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. By the time of his death, his estate was valued at some $500,000 ($10.2 million today).

Morse’s telegraph was recognized as an IEEE Milestone in 1988.

On April 1, 2012, Google announced the release of “Gmail Tap”, an April Fools’ Day joke that allowed users to use Morse Code to send text from their mobile phones. Morse’s great-great-grandnephew Reed Morse a Google engineer was instrumental in the prank, which became a real product.

Information Source: