Biography of William Blake

William Blake – English poet, painter, and printmaker.

Name: William Blake

Date of Birth: 28 November 1757

Place of Birth: Soho, London, England

Date of Death: 12 August 1827 (aged 69)

Place of Death: Charing Cross, London, England

Occupation: Poet, painter, printmaker

Father: James Blake

Mother: Catherine Wright Armitage Blake

Spouse: Catherine Boucher (m. 1782–1827)

Early Life

William Blake (an English poet, engraver, and painter) was born on 28 November 1757 at 28 Broad Street (now Broadwick St.) in Soho, London. Blake’s father, James, was a hosier. He attended school only long enough to learn reading and writing, leaving at the age of ten, and was otherwise educated at home by his mother Catherine Blake (née Wright). His writings have influenced countless writers and artists through the ages, and he has been deemed both a major poet and an original thinker.

What he called his prophetic works were said by 20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry led 21st-century critic Jonathan Jones to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC’s poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. While he lived in London his entire life, except for three years spent in Felpham, he produced a diverse and symbolically rich œuvre, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God” or “human existence itself”.

The 19th-century scholar William Rossetti characterized him as a “glorious luminary”, and “a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors”.

The dating of Blake’s texts is explained in the Researcher’s Note: Blake publication dates. These works he etched, printed, colored, stitched, and sold, with the assistance of his devoted wife, Catherine. Among his best-known lyrics, today are “The Lamb,” “The Tyger,” “London,” and the “Jerusalem” lyric from Milton, which has become a kind of second national anthem in Britain. In the early 21st century, Blake was regarded as the earliest and most original of the Romantic poets, but in his lifetime he was generally neglected or (unjustly) dismissed as mad.

Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings and poetry have been characterized as part of the Romantic Movement and as “Pre-Romantic”. A committed Christian who was hostile to the Church of England (indeed, to almost all forms of organized religion), Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American Revolutions. Though later he rejected many of these political beliefs, he maintained an amiable relationship with the political activist Thomas Paine; he was also influenced by thinkers such as Emanuel Swedenborg. Despite these known influences, the singularity of Blake’s work makes him difficult to classify.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

William Blake was born in London, England, on November 28, 1757, the second son of a mens’ clothing merchant. His parents were James Blake (1722–84) and Catherine Wright Armitage Blake (1722–92). His father came from an obscure family in Rotherhithe, across the River Thames from London, and his mother was from equally obscure yeoman stock in the straggling little village of Walkeringham in Nottinghamshire.

William Blake grew up in modest circumstances. What teaching he received as a child was at his mother’s knee, as most children did. This he saw as a positive matter, later writing, “Thank God I never was sent to school/ To be Flogd into following the Style of a Fool”.

At an early age, Blake began experiencing visions, and his friend and journalist Henry Crabb Robinson wrote that Blake saw God’s head appear in a window when Blake was 4 years old. He also allegedly saw the prophet Ezekiel under a tree and had a vision of “a tree filled with angels.” Blake’s visions would have a lasting effect on the art and writings that he produced.

At age ten Blake started at the well-known Park’s drawing school, and at age fourteen he began a seven-year apprenticeship (studying and practicing under someone skilled) to an engraver. It was as an engraver that Blake earned his living for the rest of his life. Blake’s master was the engraver to the London Society of Antiquaries, and Blake was sent to Westminster Abbey to make drawings of tombs and monuments, where his lifelong love of Gothic art was seeded. After he was twenty-one, Blake studied for a time at the Royal Academy of Arts, but he was unhappy with the instruction and soon left.

Personal Life

Blake met Catherine Boucher in 1782 when he was recovering from a relationship that had culminated in a refusal of his marriage proposal. He recounted the story of his heartbreak for Catherine and her parents, after which he asked Catherine, “Do you pity me?” When she responded affirmatively, he declared, “Then I love you.”

In August 1782, Blake married Catherine Sophia Boucher, who was illiterate. Blake taught her how to read, write, draw and color (his designs and prints). He also helped her to experience visions, as he did. Catherine believed explicitly in her husband’s visions and his genius, and supported him in everything he did, right up to his death 45 years later. His “sweet shadow of delight,” as Blake called Catherine, was a devoted and loving wife.

One of the most traumatic events of William Blake’s life occurred in 1787, when his beloved brother, Robert, died from tuberculosis at age 24. At the moment of Robert’s death, Blake allegedly saw his spirit ascend through the ceiling, joyously; the moment, which entered into Blake’s psyche, greatly influenced his later poetry. The following year, Robert appeared to Blake in a vision and presented him with a new method of printing his works, which Blake called “illuminated printing.” Once incorporated, this method allowed Blake to control every aspect of the production of his art.

Career and Works

Visions were commonplaces to Blake, and his life and works were intensely spiritual. His friend the journalist Henry Crabb Robinson wrote that when Blake was four years old he saw God’s head appear in a window. While still a child he also saw the Prophet Ezekiel under a tree in the fields and had a vision, according to his first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist (1828–61), of “a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars.” Robinson reported in his diary that Blake spoke of visions “in the ordinary unemphatic tone in which we speak of trivial matters.…Of the faculty of Vision, he spoke as One he had had from early infancy He thinks all men partake of it but it is lost by not being cultivated.”

On 4 August 1772, Blake was apprenticed to engraver James Basire of Great Queen Street, at the sum of £52.10, for a term of seven years. At the end of the term, aged 21, he became a professional engraver. No record survives of any serious disagreement or conflict between the two during the period of Blake’s apprenticeship, but Peter Ackroyd’s biography notes that Blake later added Basire’s name to a list of artistic adversaries and then crossed it out.

When he was twenty-six, he wrote a collection entitled Poetical Sketches. This volume was the only one of Blake’s poetic works to appear in the conventional printed form he later invented and practiced a new method.

Blake’s first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was printed around 1783. After his father’s death, Blake and former fellow apprentice James Parker opened a print shop in 1784 and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. Johnson’s house was a meeting-place for some leading English intellectual dissidents of the time: theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley, philosopher Richard Price, artist John Henry Fuseli, early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, and English revolutionary Thomas Paine. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the French and American revolutions and wore a Phrygian cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in France. In 1784 Blake composed his unfinished manuscript An Island in the Moon.

(Oberon, Titania, and Puck with Fairies Dancing – William Blake. c.1786)

In 1787 his beloved brother Robert died; thereafter William claimed that Robert communicated with him in visions. It was Robert, William said, who inspired him with a new method of illuminated etching. The words and or design were drawn in reverse on a plate covered with an acid-resisting substance; acid was then applied. From these etched plates, pages were printed and later hand-colored. Blake used his unique methods to print almost all of his long poems.

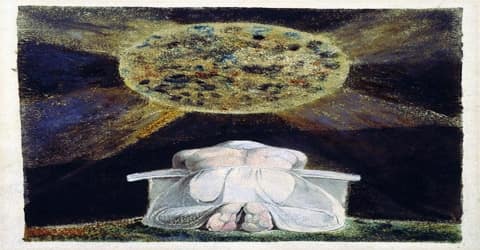

(The archetype of the Creator is a familiar image in Blake’s work)

In 1787 Blake produced Songs of Innocence (1789) as the first major work in his new process, followed by Songs of Experience (1794). The magnificent lyrics in these two collections carefully compare the openness of innocence with the bitterness of experience. They are a milestone because they are a rare instance of the successful union of two art forms by one man.

In 1800, Blake accepted an invitation from poet William Hayley to move to the little seaside village of Felpham and work as his protégé. While the relationship between Hayley and Blake began to sour, Blake ran into trouble of a different stripe: In August 1803, Blake found a soldier, John Schofield, on the property and demanded that he leave. After Schofield refused and an argument ensued, Blake removed him by force. Schofield accused Blake of assault and, worse, of sedition, claiming that he had damned the king.

(The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy, 1795. Blake’s vision of Hecate, the Greek goddess of black magic and the underworld.)

In his essay “A Vision of the Last Judgment,” Blake wrote:

I assert for My Self that I do not behold the outward Creation… ‘What’ it will be Questiond ‘When the Sun rises, do you not See around Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?’ O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying ‘Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty!’

Blake wrote to his patron William Hayley in 1802, “I am under the direction of Messengers from Heaven Daily & Nightly.” These visions were the source of many of his poems and drawings. As he wrote in his “Auguries of Innocence,” his purpose was

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

Blake returned to London in 1804 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804–20), his most ambitious work. Having conceived the idea of portraying the characters in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Blake approached the dealer Robert Cromek, with a view to marketing an engraving. Knowing Blake was too eccentric to produce a popular work, Cromek promptly commissioned Blake’s friend Thomas Stothard to execute the concept. When Blake learned he had been cheated, he broke off contact with Stothard. He set up an independent exhibition in his brother’s haberdashery shop at 27 Broad Street in Soho. The exhibition was designed to market his own version of the Canterbury illustration (titled The Canterbury Pilgrims), along with other works. As a result, he wrote his Descriptive Catalogue (1809), which contains what Anthony Blunt called a “brilliant analysis” of Chaucer and is regularly anthologized as a classic of Chaucer criticism. It also contained detailed explanations of his other paintings. The exhibition was very poorly attended, selling none of the temperas or watercolors. Its only review, in The Examiner, was hostile.

Blake was christened, married, and buried by the rites of the Church of England, but his creed was likely to outrage the orthodox. In “A Vision of the Last Judgment” he wrote that “the Creator of this World is a very Cruel Being,” whom Blake called variously Nobodaddy and Urizen, and in his emblem book For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise, he addressed Satan as “The Accuser who is The God of This World.” To Robinson “He warmly declared that all he knew is in the Bible. But he understands the Bible in its spiritual sense.” Blake’s religious singularity is demonstrated in his poem “The Everlasting Gospel” (c. 1818):

The Vision of Christ that thou dost See

Is my Visions Greatest Enemy

…

Both read the Bible day & night

But thou readst black where I read White.

Blake spent the years 1800 to 1803 in Sussex working with William Hayley, a minor poet, and the man of letters. With good intentions, Hayley tried to cure Blake of his unprofitable enthusiasms. Blake finally rebelled against this criticism and rejected Hayley’s help. In Milton (c. 1800–1810), Blake wrote an allegory (story with symbols) of the spiritual issues involved in this relationship. He identified with the poet John Milton (1608–1674) in leaving the safety of heaven and returning to earth. Also at this time in life Blake was accused of uttering seditious (treasonous) sentiments. He was later found not guilty but the incident affected much of Blake’s final epic (long lyric poem highlighting a single subject), Jerusalem (c. 1804–1820).

From 1809 to 1818, he engraved few plates (there is no record of Blake producing any commercial engravings from 1806 to 1813). He also sank deeper into poverty, obscurity, and paranoia.

Blake had become a political sympathizer with the American and French Revolutions. He composed The Four Zoas as a mystical story predicting the future showing how evil is rooted in man’s basic faculties reason, passion, instinct, and imagination. Imagination was the hero.

In 1818, he was introduced by George Cumberland’s son to a young artist named John Linnell. A blue plaque commemorates Blake and Linnell at Old Wyldes’ at North End, Hampstead. Through Linnell, he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. The group shared Blake’s rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. Aged 65, Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job, later admired by Ruskin, who compared Blake favorably to Rembrandt, and by Vaughan Williams, who based his ballet Job: A Masque for Dancing on a selection of the illustrations.

In 1819, however, Blake began sketching a series of “visionary heads,” claiming that the historical and imaginary figures that he depicted actually appeared and sat for him. By 1825, Blake had sketched more than 100 of them, including those of Solomon and Merlin the magician and those included in “The Man Who Built the Pyramids” and “Harold, Killed at the Battle of Hastings”; along with the most famous visionary head, that included in Blake’s “The Ghost of a Flea.”

More publicly visible were Blake’s engravings of his enormous design of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims (1810), his 22 folio designs for the Book of Job (1826), and his 7 even larger unfinished plates for Dante (1826–27). Though only the Chaucer sold well enough to repay its probable expenses during Blake’s lifetime, these are agreed today to be among the greatest triumphs of line engraving in England, sufficient to ensure Blake’s reputation as an engraver and artist even had he made no other watercolors or poems.

(Blake’s The Lovers’ Whirlwind illustrates Hell in Canto V of Dante’s Inferno)

The commission for Dante’s Divine Comedy came to Blake in 1826 through Linnell, with the aim of producing a series of engravings. Blake’s death in 1827 cut short the enterprise, and only a handful of watercolors was completed, with only seven of the engravings arriving at the proof form. Even so, they have earned praise:

‘The Dante watercolors are among Blake’s richest achievements, engaging fully with the problem of illustrating a poem of this complexity. The mastery of watercolor has reached an even higher level than before, and is used to extraordinary effect in differentiating the atmosphere of the three states of being in the poem’.

Blake did some significant work, including his designs for Milton’s poems L’Allegro and Il Penseroso (1816) and the writing of his own poem The Everlasting Gospel (c. 1818). He was also sometimes reduced to writing for others, and the public did not purchase or read his divinely inspired predictions and visions. After 1818, however, conditions improved. His last six years of life were spent at Fountain Court surrounded by a group of admiring young artists. Blake did some of his best pictorial work: the illustrations to the Book of Job and his unfinished Dante.

Blake seems to dissent from Dante’s admiration of the poetic works of ancient Greece, and from the apparent glee with which Dante allots punishments in Hell (as evidenced by the grim humor of the cantos). Blake shared Dante’s distrust of materialism and the corruptive nature of power and clearly relished the opportunity to represent the atmosphere and imagery of Dante’s work pictorially. Even as he seemed to be near death, Blake’s central preoccupation was his feverish work on the illustrations to Dante’s Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the very last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching.

Blake’s last years, from 1818 to 1827, were made comfortable and productive as a result of his friendship with the artist John Linnell. Through Linnell, Blake met the physician and botanist Robert John Thornton, who commissioned Blake’s woodcuts for a school text of Virgil (1821). He also met the young painters George Richmond, Samuel Palmer, and Edward Calvert, who became his disciples, called themselves “the Ancients,” and reflected Blake’s inspiration in their art.

Linnell also supported Blake with his commissions for the drawings and engravings of the Book of Job (published 1826) and Dante (1838), Blake’s greatest achievements as a line engraver. In these last years, Blake gained a new serenity. Once, when he met a fashionably dressed little girl at a party, he put his hand on her head and said, “May God make this world to you, my child, as beautiful as it has been to me.”

In particular, Blake is sometimes considered (along with Mary Wollstonecraft and her husband William Godwin) a forerunner of the 19th-century “free love” movement, a broad reform tradition starting in the 1820s that held that marriage is slavery, and advocated the removal of all state restrictions on sexual activity such as homosexuality, prostitution, and adultery, culminating in the birth control movement of the early 20th century. Blake scholarship was more focused on this theme in the earlier 20th century than today, although it is still mentioned notably by the Blake scholar Magnus Ankarsjö who moderately challenges this interpretation. The 19th-century “free love” movement was not particularly focused on the idea of multiple partners, but did agree with Wollstonecraft that state-sanctioned marriage was “legal prostitution” and monopolistic in character. It has somewhat more in common with early feminist movements (particularly with regard to the writings of Mary Wollstonecraft, whom Blake admired).

(“Head of William Blake” by James De Ville. Life mask taken in a plaster cast in September 1823, Fitzwilliam Museum.)

Some scholars have noted that Blake’s views on “free love” are both qualified and may have undergone shifts and modifications in his late years. Some poems from this period warn of the dangers of predatory sexuality such as The Sick Rose. Magnus Ankarsjö notes that while the hero of Visions of the Daughters of Albion is a strong advocate of free love, by the end of the poem she has become more circumspect as her awareness of the dark side of sexuality has grown, crying “Can this be love which drinks another as a sponge drinks water?” Ankarsjö also notes that a major inspiration to Blake, Mary Wollstonecraft, similarly developed more circumspect views of sexual freedom late in life. In light of Blake’s aforementioned sense of human ‘fallenness’ Ankarsjö thinks Blake does not fully approve of sensual indulgence merely in defiance of law as exemplified by the female character of Leutha since in the fallen world of experience all love is enchained. Ankarsjö records Blake as having supported a commune with some sharing of partners, though David Worrall read The Book of Thel as a rejection of the proposal to take concubines espoused by some members of the Swedenborgian church.

Death and Legacy

In the final years of his life, William Blake suffered from recurring bouts of an undiagnosed disease that he called “that sickness to which there is no name.” Blake died in his cramped rooms in Fountain Court, the Strand, London, on Aug. 12, 1827. His disciple Richmond wrote,

Just before he died His Countenance became fair His eyes brightened and He burst out in Singing of the things he Saw in Heaven. In truth, He Died like a saint, as a person who was standing by Him Observed.

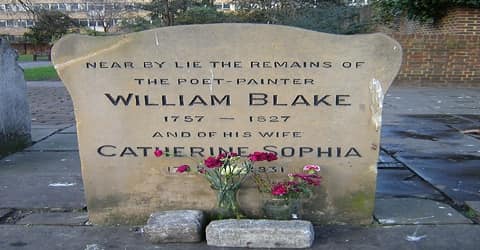

(Monument near Blake’s (formerly unmarked) grave at Bunhill Fields in London. A gravestone to mark the actual spot was unveiled at a public ceremony on 12 August 2018.)

Catherine paid for Blake’s funeral with money lent to her by Linnell. Blake’s body was buried in a plot shared with others, five days after his death on the eve of his 45th wedding anniversary at the Dissenter’s burial ground in Bunhill Fields, in what is today the London Borough of Islington. His parents’ bodies were buried in the same graveyard.

Following Blake’s death, Catherine moved into Tatham’s house as a housekeeper. She believed she was regularly visited by Blake’s spirit. She continued selling his illuminated works and paintings, but entertained no business transaction without first “consulting Mr. Blake”. On the day of her death, in October 1831, she was as calm and cheerful as her husband and called out to him “as if he were only in the next room, to say she was coming to him, and it would not be long now”.

Blake’s history does not end with his death. In his own lifetime, he was almost unknown except to a few friends and faithful sponsors. He was even suspected of being mad. But interest in his work grew during the middle of the nineteenth century, and since then very committed reviewers have gradually shed light on Blake’s beautiful, detailed, and difficult mythology. He has been acclaimed as one who shares common ideals held by psychologists, writers (most notably William Butler Yeats (1865–1939)), extreme students of religion, rock-and-roll musicians, and people studying Oriental religion. The works of William Blake have been used by people rebelling against a wide variety of issues, such as war, conformity (behaving in a certain way because it is accepted or expected), and almost every kind of repression.

Blake’s grave is commemorated by two stones. The first was a stone that reads “Near by lie the remains of the poet-painter William Blake 1757–1827 and his wife Catherine Sophia 1762–1831”. The memorial stone is situated approximately 20 meters (66 ft) away from the actual grave, which was not marked until 12 August 2018. For years since 1965, the exact location of William Blake’s grave had been lost and forgotten. The area had been damaged in the Second World War; gravestones were removed and a garden was created. The memorial stone, indicating that the burial sites are “nearby”, was listed as a Grade II listed structure in 2011. A Portuguese couple, Carol & Luis Garrido rediscovered the exact burial location after 14 years of investigatory work, and the Blake Society organized a permanent memorial slab, which was unveiled at a public ceremony at the site on 12 August 2018.

Unappreciated in life, William Blake has since become a giant in literary and artistic circles, and his visionary approach to art and writing have not only spawned countless, spellbound speculations about Blake, they have inspired a vast array of artists and writers.

Information Source: