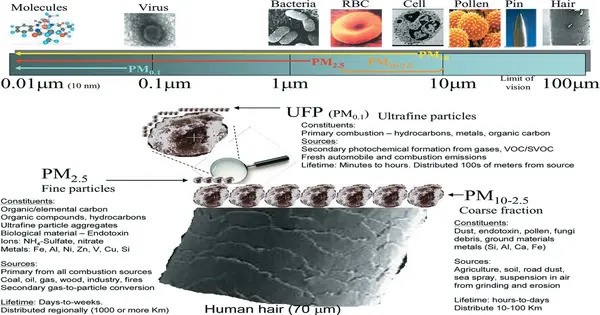

A pioneering method to simulate how microscopic particles move through the air could boost efforts to combat air pollution, a study suggests. Tiny particles found in exhaust fumes, wildfire smoke and other forms of airborne pollution are linked with serious health conditions such as stroke, heart disease and cancer, but predicting how they move is notoriously difficult, researchers say.

Now, scientists have developed a new computer modelling approach that dramatically improves the accuracy and efficiency of simulating how so-called nanoparticles behave in the air. In practice, this could mean simulations that currently can take weeks to run could be completed in a matter of hours, the team says.

Better understanding the behaviour of these particles – which are small enough to bypass the body’s natural defences – could lead to more precise ways of monitoring air pollution, researchers say.

Using the UK’s national supercomputer ARCHER2, researchers from the Universities of Edinburgh and Warwick have created a method that allows a key factor governing how particles travel – known as the drag force – to be calculated up to 4,000 times faster than existing techniques.

Airborne particles in the nanoscale range are some of the most harmful to human health – but also the hardest to model. Our method allows us to simulate their behaviour in complex flows far more efficiently, which is crucial for understanding where they go and how to mitigate their effects.

Dr Giorgos Tatsios

At the heart of the team’s approach is a new way of modelling the way air flows around nanoparticles. It involves a mathematical solution based on how air disturbances caused by nanoparticles fade with distance. When applied to the simulation, researchers can zoom in much closer to particles without compromising accuracy.

This differs from current methods, which involve simulating vast regions of surrounding air to mimic undisturbed air flow and require far more computing power, the team says. By enabling fast and precise simulations at the nanoscale, the new approach could help better predict how these particles will behave inside the body, the team says.

As well as potentially aiding the development of improved air pollution monitoring tools, the advance could also inform the design of nanoparticle-based technologies, such as lab-made particles for targeted drug delivery, the team adds. The study, published in the Journal of Computational Physics, was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Lead author Dr Giorgos Tatsios, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering, said: “Airborne particles in the nanoscale range are some of the most harmful to human health — but also the hardest to model. Our method allows us to simulate their behaviour in complex flows far more efficiently, which is crucial for understanding where they go and how to mitigate their effects.”

Professor Duncan Lockerby, of the University of Warwick’s School of Engineering, said: “This approach could unlock new levels of accuracy in modelling how toxic particles move through the air — from city streets to human lungs — as well as how they behave in advanced sensors and cleanroom environments.”