M-banking & M-payment system in the developing world

The terms m-banking, m-payments, m-transfers, m-payments, and m-finance refer collectively to a set of applications that enable people to use their mobile telephones to manipulate their bank accounts, store value in an account linked to their handsets, transfer funds, or even access credit or insurance products. This paper uses the compound term m-banking / m-payments systems to refer to the most common features. The first targets for these applications were consumers in the developed world. By complementing services offered by the banking system, such as checkbooks, ATMs, voicemail/landline interfaces, smart cards, point-of-sale networks, and Internet resources, the mobile platform offers a convenient additional method for managing money without handling cash (Karjaluoto, 2002). For users in the developing world, however, the appeal of these m-banking/ m-payments systems may be less about convenience and more about accessibility and affordability (Cracknell, 2004; infoDEV, 2006). An exploration is underway, between banks, mobile operators, hardware and software providers, regulatory agencies, donors, and users, to determine the shape of m-banking/m-payments services in the developing world (infoDEV, 2006; Ivatury, 2004; Ivatury & Pickens, 2006; Porteous, 2006). Mobile phone operators have identified m-banking/m-payments systems as a potential service to offer customers, increasing loyalty while generating fees and messaging charges (infoDEV, 2006).

Financial institutions, which have had difficulty providing profitable services through traditional channels to poor clients, see m-banking/m-payments as a form of ‘branchless banking’ (Ivatury & Mas, 2008), which lowers the costs of serving low-income customers. Government regulators see a similar appeal but are working on the legal implications of the technologies, particularly concerning security and taxation. There is no universal form of m-banking; rather, purposes and structures vary from country to country. The systems offer a variety of financial functions, including micro-payments to merchants, bill-payments to utilities, P2P transfers between individuals, and long-distance remittances. Currently, different institutional and business models deliver these systems. Some are offered entirely by banks, others entirely by telecommunications providers, and still others involve a partnership between a bank and a telecommunications provider (Porteous, 2006). Regulatory factors, which can vary dramatically from country to country, play a strong role in determining which services can be delivered via which institutional arrangements (Mortimer-Schutts, 2007).

Most m-banking/m-payments systems in the developing world enable users to do three things: (1) Store value (currency) in an account accessible via the handset. If the user already has a bank account, this is generally a question of linking to a bank account. If the user does not have an account, then the process creates a bank account for her or creates a pseudo bank account, held by a third party or the user’s mobile operator. (2) Convert cash Asian Journal of Communication in and out of the stored value account. If the account is linked to a bank account, then users can visit banks to cash-in and cash-out. In many cases, users can also visit the GSM providers’ retail stores. In the most flexible services, a user can visit a corner kiosk or grocery store (perhaps the same one where he or she purchases airtime) and transact with an independent retailer working as an agent for the transaction system. (3) Transfer stored value between accounts. Users can generally transfer funds between accounts linked to two mobile phones, by using a set of SMS messages (or menu commands) and PIN numbers. The new services offer a way to move money from place to place and present an alternative to the payment systems offered by banks, remittance firms, pawn shops, etc. The uptake of m-banking/m-payments systems has been particularly strong in the Philippines, where three million customers use systems offered by mobile operators Smart and Globe (infoDEV, 2006); in South Africa, where 450,000 people use Wizzit (‘the bank in your pocket’) (Ivatury & Pickens, 2006) or one of two other national systems (Porteous, 2007); and in Kenya, where nearly two million users registered with Safaricom M-Pesa system within a year of its nationwide rollout (Ivatury & Mas, 2008; Vaughan, 2007).

Market size

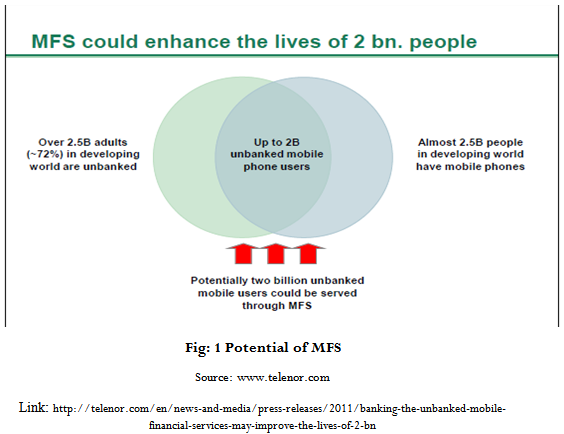

In the developing world, more than 2.5 billion adults—or approximately 72 percent of the developing population—are un-banked, meaning they have no access to financial services. At the same time, nearly 2.5 billion people in developing countries have mobile phones. This means that there could be up to 2 billion mobile phone users who are not financially included and who could be served through mobile financial services (MFS).

The un-banked have an urgent need for formal financial services, but they lack access for a variety of reasons, and make use of informal channels instead. For instance, out of a need to manage the short-term volatility of cash flows, they often borrow money from, or save money with, friends and relatives. To manage low-frequency but high-cost risks, they obtain short-term credit from landlords, shopkeepers, or employers, depending on the situation. When they need a significant lump sum of cash, they sometimes participate in informal savings clubs or will use illegal moneylenders. And to receive money transfers from family working elsewhere, for instance, they may seek out informal remittance channels.

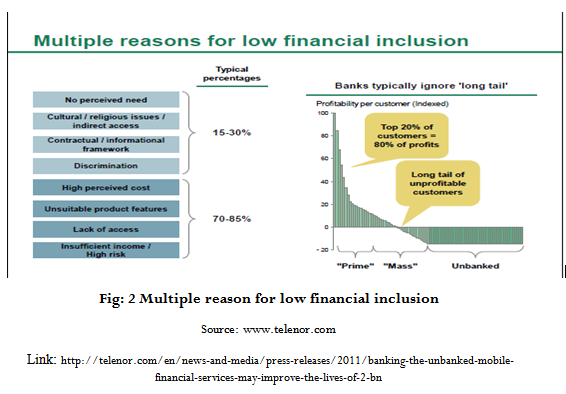

The informal financial services prevalent among the un-banked are often costly, in transparent, and risky. Populations are without formal financial inclusion for a variety of reasons. Overall, an estimated 15 percent to 30 percent of the un-banked fall into one of these four categories:

• There is no perceived need for financial services.

• Cultural or religious reasons keep them from seeking out services, or they have no direct access to a bank branch.

• An informational or contractual framework puts banking services out of reach.

• They face (real or perceived) discrimination.

A larger proportion, an estimated 70 percent to 85 percent, is un-banked for any of the following reasons:

• The cost of services is too high.

• The products offered do not suit their needs.

• Financial institutions see their low income as too great a risk.

Another reason for low financial inclusion is that banks tend to ignore the “long-tail” customers, who they are unable to serve profitably. For banks, the top 20 percent of customers can contribute up to 80 percent of the profits; hence there is little economic incentive to bank the un-banked.

Advantages of MFS

Mobile financial services providers have brought five distinct advantages over traditional banks to give the un-banked and under banked access to the benefits of financial services in Bangladesh.

A focus on “long-tail” customers: Telcos have extensive experience targeting their customers and understanding their needs, making it possible for them to deepen and broaden the relationships they have with existing customers. In contrast, banks have typically given the lion’s share of their attention to the wealthiest customers, ignoring the “long-tail,” which they are unable to serve profitably.

Key infrastructure in customers’ hands: Mobile customers already have the critical piece of infrastructure they need to access MFS, since the mobile SIM card can act as a secure identification and authentication device.

Customer relationship: Many of the un-banked already have relationships with mobile operators, which mean their usage history is available. This gives telcos an advantage in knowing who potential financial services customers are and where they live. It gives them information on transactional patterns, which can become a basis for building a credit history, as well as an established channel for communication with customers.

Brand recognition: The population in general has had limited interactions with large, formal financial institutions, which has created a “trust gap” that could be a potential barrier to financial inclusion. Telecom companies, on the other hand, are typically well known even among the poorest segments of society, are considered safe, and are associated with instant transmission—through text messaging, or SMS, for instance.

Large distribution network: Unlike traditional banks, telecoms have behind them an extensive, nationwide network of merchants who are accustomed to working as commissioned agents. These companies have broad experience working with such partners on both pricing and product distribution.

In a nut shell it can be said that Mobile financial services’ basic qualities can help the un-banked overcome barriers and reap the benefits of financial services. MFS can be used by nearly everyone at any time of day or night and from anywhere, eliminating the accessibility issues presented by traditional banking. In addition, MFS provides secure services at a low cost.

In fact, Telecommunications companies (telcos) bring five unique advantages over traditional banks. They have traditionally focused on all customers, not just the most profitable among them. They already have a secure device—the mobile phone—in customers’ hands. Unlike banks, telcos have existing relationships with these customers and have already established trust. And telcos have the added benefit of a large distribution network.

Telcos brings five unique advantages:

Focus on all customers

Secure device already in customer’s hand

Existing customer relationship

Trusted & familiar brands

Large distribution network

Economic and Social Benefits

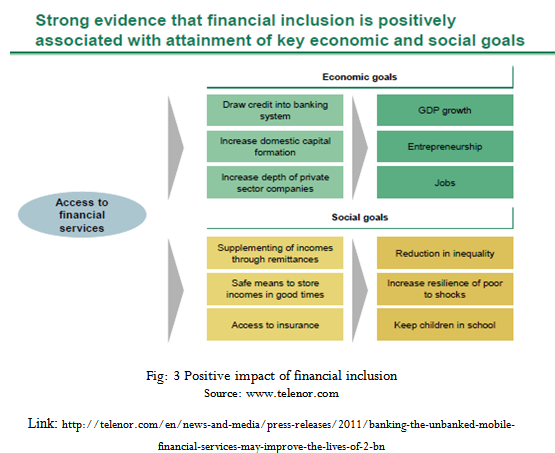

Social benefits include the supplementing of incomes through remittances, providing a safe means to store income during good times, and access to insurance. These impacts lead to larger social benefits, such as a reduction in financial exclusion, an increase in the poor population’s resilience to shocks, and the improved ability to keep children in school should a financial shock occur.

Evidence shows that financial inclusion can increase a nation’s GDP1. Access to credit facilitates entrepreneurship and new business creation2. The formalization of remittances and domestic payments adds an “accounting benefit” to the economy, and the increased savings within the banking system facilitates the expansion of credit. Overall, mobile financial services can reduce financial exclusion by 5 percent to 20 percent through 2020 and increase GDP by up to 5 percent, with Pakistan, for instance,potentially seeing a 3 percent uplift. This increase in GDP will also create additional jobs and businesses, and stimulate additional tax revenues for governments.

From a social perspective, financial inclusion promotes inclusive growth3, which is especially meaningful for the more developed countries in the study, such as Serbia and Malaysia. In Malaysia, for example, economic inequality could be reduced by an additional 5 percent by 2020 with MFS, relative to the baseline. The benefits of MFS accrue to the poorest of the population by supporting entrepreneurs with savings and credit, reducing leakages and costs imposed by middlemen, and facilitating domestic and international remittances and transfers.

For the poor in any country, financial shocks put a severe financial burden on families that can be hard to overcome. Such shocks can come from natural disasters, unexpected medical emergencies, or loss of income due to injury, or even bad luck. In Bangladesh, for instance, floods occur on average every five years, last 35 days, and affect up to 75 percent of the population. Average flood damage cost is US$ 365 per household, or 30 percent of the average annual household income. Most of the damage hits crops and property4

Preconditions for adoption

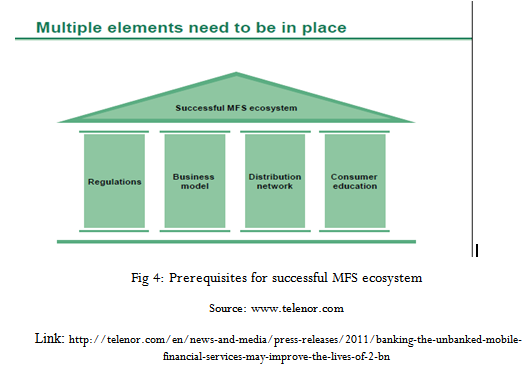

To establish a successful MFS ecosystem, several elements need to be in place.

MFS Impact on Firms, Merchants, and Middlemen

The adoption of mobile financial services can decrease administrative costs for companies. Many firms, such as utility companies, spend significant time and money on the administration and processing of paper bills. Incorporating electronic receipts and reporting can reduce costs and improve speed and accuracy, reducing erroneous charges for arrears, for example. In addition, MFS will increase transaction speeds and reduce outstanding credit times, minimizing the time it takes to collect and inquire after payments.

A byproduct of companies’ reduced administrative duties is an increase in the flow of customers—and revenues—to over-the-counter MFS agents. The merchants who take on these jobs will benefit from the growing sales of financial services, larger revenues from the sales of ordinary goods, and an improved social standing as a result of their work.

Another byproduct, however, will be a reduced need for middlemen, some of whom will experience a cut in income. For example, the livelihoods of some middlemen have been based on the transport of money for remittances and payments, and some have worked as money collectors for informal savings and credit schemes. All of those jobs will be less in demand as mobile services spread and their products become more popular. Thanks to MFS, however, new opportunities will arise—such as jobs for formal banking agents—for those willing to be trained and licensed.

Existing payment mechanisms

The role of existing mediated transfers and other financial services also deserves scrutiny. A large proportion of the volume of m-transactions may reflect existing transactional relationships, shifted over to the new channels. This is not to say that a shift is not itself valuable; there are significant benefits of cost, reliability, safety, flexibility, and immediacy associated with m-banking/m-payments systems. However, it is important for industry, researchers, and policymakers to understand the transactional networks and behaviors that already exist. An antecedent to this argument comes from the microfinance sector. Arguing that ‘it is no longer acceptable for prospective providers not to inform themselves of what their future clients are already doing and what services they appear to need,’ Ruthven (2002, p. 269) identified a broad array of ‘money mosaics’ operating in a Delhi slum. These ‘financial relations are frequently embedded in other social relations which reflect the diversity of social, security, and economic needs which people have. It highlights the relatively small role of commercial transactions in people’s financial lives, and the importance, extent and diversity of personal networks’ (Ruthven, 2002, p. 267).

In the case of m-banking/m-payments channels, pawn shops, bus companies, the post office, hand-carrying by friends and family, underground money transfer mechanisms (such as China’s fei ch’ien ‘flying money,’ a network of affiliates allowing users to put money into the network in one city and have it available in another without the actual banknotes making the trip; Maurer, 2008), and formal transfer services like Western Union all have their adherents, and the list is longer when one includes alternative savings and credit mechanisms like chit funds and moneylenders. There are communication issues: transfers are exchanges at a distance and, as Ruthven points out, there is an implicit or explicit network of communication and information exchange embedded into almost every transaction. Remittances,3 in particular, are a context in which it is difficult to separate financial transactions from symbolic meaning and social bonding (Hart, 2000; Singh, 2007).4

The social embeddedness of economic transactions

There is a litany of social/contextual influences on m-banking/m-payments use. Both macro-level cultural factors and micro-level, locally-negotiated norms in families and among peers, particularly about money, are at play (Zelizer, 1994). For example, respondents in focus groups we conducted in Manila (Donner, 2007b) explained that, while they would certainly transfer money to a family member (a gift), they would not do so to an acquaintance (a loan). Technically, the actions are the same. Socially, they are miles apart. Practitioners and policymakers are already concerned about validating money transactions under conditions of sharing behavior (infoDEV, 2006), in which two people use the same handset. However, others suggest that m-banking/m-payments systems may alter patterns of money-sharing within families by giving women greater autonomy and control over household savings (von Reijswoud, 2007).

Cross-cutting themes in studies of m-banking/m-payments use. The use questions described above (skills and mental models, alternatives, and social norms) each represent fruitful paths for future research. When such studies of m-banking/ m-transactions use in the developing world appear, it is likely that they will touch, implicitly or explicitly, on cross-cutting themes shared by studies of other mediated communication technologies. There is little need for a new ‘theory of m-banking.’ Rather, our existing toolkit of theories of technology use, and particularly technology use in the service of economic and social development (ICTD), is sufficiently robust to handle the introduction of this new technology (e.g., Sandvig & Sawhney, 2006). Rather, the task at hand for communication researchers is to find ways to have the existing theory inform and strengthen the assessments of impact and diffusion, of design and policy, which are occurring at this time as diverse stakeholders are establishing the mobile payments landscape. While some periods of alternating exuberance and introspection are to be expected in the realm of new technology development and policy, the opportunity exists at this time for theory to temper some of the more dramatic swings, at least as far as m-banking/ m-payments as an ‘ICT4D’ is concerned.

In this section, we introduce three cross-cutting themes, each drawing on the existing body of research on technology use, which illustrate social structures underlying m-banking/ m-payments and can guide decision-makers and practitioners as they build and evaluate these systems over time. These themes are the bi-directionality of influence, amplification versus change, and the multi-dimensionality of trust. As possible themes and theoretical perspectives, these three are neither mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive. However, they do help contextualize issues encountered in these early days of the technology. These three themes are sufficient to illustrate this paper’s primary argument: the importance of ‘use studies’ as input to the evaluation of adoption and impact of m-banking/ m-payments systems. A willingness to examine the bi-directionality of influence between communication technologies and the social structures in which they exist, a focus on the ‘dynamic interactions between people and technology’ (Orlikowski & Iacono, 2001), is a hallmark of many studies applying a ‘use heuristic’ (Latour, 1987) or ‘ensemble’ view (Orlikowski & Iacono, 2001). Within the communication research tradition, two prominent examples of these approaches are adaptive structuration theory (Poole & DeSanctis, 1990), usually applied to organizational settings and domestication theory (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992), and usually applied to domestic settings. Mobile telephones have also been the subjects of a wide range of studies complicating the directionality of influence, from technological affordances to user choices to social structures and back again (Donner, 2008; Haddon, 2003).

Studies that take ‘ensemble’ approaches to assessing the spread of m-banking/m-payments systems are needed. Like text messaging (Ling, 2004), multimedia messaging (Ling & Julsrud, 2005), and missed calls (Donner, 2007c), the set of social norms and expected behaviors surrounding mobile-enabled financial services will evolve over time and probably will differ from place to place. For example, respondents in the Manila focus groups reported a norm of ‘gifts not loans,’ based partially on their family structures and partially on their experience with the m-banking/m-payments system. Wholly different norms might emerge within another system, where perhaps early adopters were not dispersed families seeking a channel for cost-effective remittances but rather traders looking for a way to protect money from theft on deserted roads (as in, perhaps, Northern Kenya). In that case, transfers to near-strangers might be perfectly acceptable, even expected.

A second cross-cutting theme involves the capacity of a communication technology to amplify existing relational and social structures as well as to alter them. When we speak of the ‘impact’ of a technology on a social structure, a particularly common frame within the ICTD perspective, we often seek insight into how technologies change social structures, but the reverse can also be true (Harper, 2003). If we look with this lens, we may find that m-banking/m-payments systems may increase the volume or frequency of existing transactional patterns rather than alter the target of those transactions. For example, in the Manila focus group, of the 10 people using the system, only one had used it to trade with somebody that they had not previously traded with using another channel; a woman who had used the service to start her own informal money-lending business (Donner, 2007b). Additional findings of this kind may qualify some of the ‘transformational’ language used concerning mobile banking to this point. A final cross cutting issue involves the introduction of ‘trust’ as a factor in the

analysis of m banking/m-payments use. Early evidence and intuition alike suggests that trust plays a role in use (Ivatury, 2004; Porteous, 2007).

For example, users feel more comfortable with at least some face-to-face contact and assistance while using an m-banking/m-payment system like Wizzit (Ivatury & Pickens, 2006). Luarna and Lin (2005) proposed a modified technology acceptance model that included a trust variable (perceived credibility) to predict m-banking adoption in Taiwan. Yet their modification also included another variable, self-efficacy, and a form of trusting one ’s self. Indeed, trust itself is a multifaceted concept, which must be handled carefully in any analysis of m-banking/m-payments use (Benamati & Serva, 2007). Trust is a cross-cutting concept in that people can trust (or mistrust) their own skills. They can trust the interface, the network across which their funds travel, the representatives of the institutions (channels) who control their money, and/or trust the institutions themselves (Maurer, 2008). Of course, they can differentially trust various people in their networks: some might be eligible as exchange partners using m-banking/m-payments systems while others might not. These forms of trust may change over time with use of the system. People might become more or less trusting along any of these dimensions as their experience of the system changes, relative to friends, family, and others in the community.

The role of trust is a cross-cutting issue because multiple research traditions examine economic transactions in their social context: not as discrete acts but as markers and reinforcements of a set of interrelated responsibilities, roles, and transactional networks in which trust plays a central role (Burt, 1992; Geertz, 1978; Granovetter, 1985). Often these transactions are seen as either being structured by or creating a form of ‘social capital’ (Coleman, 1988). These transactions need not be face-to-face; researchers have used socialcapital/ social-networks lenses to explore how the information technologies generate and reinforce social/economic relationships in ways that provide ‘returns’ to actors (Huysman & Wulf, 2004; Sawyer, Crowston, Wigand, & Allbritton, 2003). For example, Horst and Miller (2006) described the practice of ‘link up’ in Jamaica, where mobiles are used quite strategically to build and maintain networks of resources for future assistance or loans. Initial reports from an ongoing ethnographic project in Kenya elaborate these dimensions, distinguishing the complexities of trust in the local m-banking middleman from trust in the telco that runs it and from the government that (presumably for many users) controls the whole operation (Morawczynski & Miscione, 2008). However, there is room for more work that assesses which forms of trust are supported by m-banking/m-payments use, particularly among low-income users.

Mediating informal credit mechanisms in urban Bangladesh

Using the three cross-cutting themes identified above, we will now present and analyze the results of an exploratory study we conducted in urban Bangladesh. This case study focuses on the importance of informal credit mechanisms among small enterprises in developing countries and explores some issues associated with using m-banking/m-payments systems to mediate those mechanisms. Despite Bangladesh’s growing role as an international hub for IT services and innovation, the majority of enterprises in Bangladesh (agricultural and nonagricultural alike) are not participants in the IT boom. Most are small, with 10 or fewer employees, and most are informal, operating in cash-only environments without formal books, bank accounts, or regular tax payments. For many small and informal firms, access to affordable credit is a constant struggle. In recent years, microfinance institutions have stepped into the gaps left by banks and have begun to provide affordable alternatives to moneylenders and other informal sources. However, surveys conducted in Hyderabad (Donner, 2007a) suggested that, for many smaller firms, extending credit informally to customers was as big a challenge as securing credit for the enterprise from lending sources (see also, Financial Diaries, 2006). Credit cards and formal financing sources are scarce; informal credit relationships between customers and suppliers resemble those detailed by Geertz (1963).

These ongoing credit relationships are both a blessing and a curse: although they bind customers to certain suppliers, they strain suppliers’ cash flows. If an enterprise is to prosper, these informal credit relationships must be managed skillfully. Thus, we decided to explore how an m banking/m-payments system might be used within the context of the supplier/client relationship. There are some efforts to use the mobile channel to service formal credit from banks or microfinance institutions, but these are not nearly as prevalent as stored-value or transaction and transfer facilities (Ivatury & Mas, 2008). Indeed, at the time of our study in mid-2007, there were no m-banking/mtransfers services available to ‘unbanked’ mobile users in Bangladesh. As an exploratory study, we did not test formal hypotheses about the attributes of m-banking; nevertheless, the line of questioning was similar to the cross-cutting themes identified above.

In July and August 2011, we conducted on-site interviews with owners of small enterprises in one of Bangladesh’s largest cities, Dhaka. We recruited participants via face-to-face requests and visits. In choosing the sample for the qualitative interviews, we made efforts to ensure variety by interviewing enterprise operators from different communities within Dhaka, taking into consideration various economic sectors. A total of 20 businesses were interviewed for the analysis with a sector distribution of 30% manufacturing, 40% retail, and 30% services. The average number of employees was 4.4, with 70% having five or fewer employees. The interactions consisted of a mix of structured closed-ended questions and open-ended, semi-structured interview questions.

Findings Face-to-face interactions dominate customer interactions, even among those with relatively complex ICT behaviors (see also Donner, 2007a; Duncombe & Heeks, 2002; Molony, 2006). While mobiles were valued by businesses for some types of transactions, and specifically for their perceived ability to allow business owners to work with clients outside their proximity, most respondents reported that their day-to-day communication needs were best met by face-to-face interactions. The majority of respondents did not accept credit cards and relied for the most part on a cash-and-carry business scheme.

Against this background of face-to-face and cash-based interactions, the majority of participants did extend informal credit to at least some of their clients, some of the time. Sixteen of 20 did so at the time of the interview; another three of 20 had done so in the past. Decisions about whom to lend to and on what terms depended on the type of relationship and on mutual trust. Trust had a dyadic component (did the entrepreneur trust the client?) and a network component. Clients embedded in an overlapping social network of friends and business partners were generally more trustworthy than isolates (Granovetter, 1985).

Broadly speaking, our interviews helped distinguish between three kinds of businesses according to their attitudes towards credit, the location of their customers, and the degree of formality. Each had a different take on the appeal of using SMS to keep in touch with clients and, particularly, to bill them or update them on credit outstanding. Relational businesses were the most insular; their owners refrained from extending credit to people they did not know or who were not in their close business network. These informal businesses had simpler and more straightforward needs that might be better met by ‘organic’ information systems instead of more complex ICTs. Although most participants in this category communicated their desire to have a mobile phone, those without a mobile stressed the issue of affordability. Locational enterprises were more likely than relational enterprises to negotiate and track credit without formal arrangements between parties.

Their method of ensuring compliance was based on knowledge of the location of the client’s residence. Those ‘in the neighborhood’ could receive informal credit; those outside, generally, could not. Finally, the five formal enterprises with which we spoke were mostly engaged in manufacturing, were larger than the other enterprises, and were more active users of information technology (Duncombe & Heeks, 2002), including accounting software. All of the formal businesses extended credit to clients and were more open to the idea of giving credit to people outside their business network. Members of this group, nevertheless, reported frequent reliance on oral arrangements for credit terms with both customers and suppliers/partners.

Across all the groups, respondents were more open to the idea of using a mediated message to stay in touch with clients, but the majority of respondents (95%) expressed varying degrees of concern about using an SMS to discuss money matters, particularly credit. A respondent reported: ‘It is not right to use SMS to remind customers about payments because it is too impersonal . . . It is just not polite to when it comes to monetary matters.’ Another had already abandoned mobile-mediated reminders of this sort, blaming the caller ID feature, which gave debtors who were trying to avoid him the ability to avoid his calls. Of course, we should not dismiss the idea of mobile-mediated informal credit relationships based on only 20 interviews. However, the basic results echo recent work (Molony, 2006) that illustrates the importance of nuanced face-to-face conversation in the maintenance of an oral, non-secured agreement to extend credit between supplier and client. Moreover, the results of this case study illustrate each of the cross-cutting themes described in the earlier sections.

A juxtaposition of two comments from respondents illustrates the likely bi-directionality of influence between m-banking systems and their users. One respondent offered this assessment: ‘On the one hand, it gives you instant connectivity, and on the other, it eats away at your personal time.’ Another explained: ‘I use SMS to keep my clients informed about little things in order to not disturb them.’ The first comment illustrates a sensitivity to the way the mobile alters one’s availability to others and the management of one’s personal time, a phenomenon described as ‘perpetual contact’ (Katz & Aakhus, 2002). The second comment puts the locus of action with the user, not the technology. The second Respondent’s actions, calibrated so as not to disturb another person, are part of an ongoing process of normative formation, as users evaluate which kinds of mobile behaviors are appropriate, with whom, and at what time. As m-banking systems spread, they will alter the payments landscape, but in so doing, they (1) will have to be understood and deployed by people in light of their existing expectations about what is appropriate when it comes to money and to telecommunications and (2) will prompt the development of a specific set of norms about how much to send, to whom, and at what time.

The differences between assessing impact as amplification vs. change were also apparent. When businesses with mobiles discussed their utility, it was in terms of expanding client networks as well as improving relationships with existing clients. One user reported that mobile use had helped him

expand his clientele; he was now able to ‘communicate long distance through it.’ However, the owner of a simple retail establishment said nothing about new customers rather that he used mobiles to ‘keep up with the pace of his clients and life in the city’ (e.g., Townsend, 2000). Finally, the multi-dimensionality of the notion of trust was clear. One participant reported: ‘I do not use SMS because a lot of my customers are not educated enough to understand how it works. When it comes to credit, I just only give it to people I know and trust.’ This statement contains an assessment of the skills of the client, as well as his or her trustworthiness. Another participant cited her own experience and ability to judge a person’s creditworthiness: ‘When I extend credit, I can judge the customer’s objective and their trustworthiness because I have been in the business for so long.’ Trustworthiness is in the eyes of the lender and is not a single attribute (but rather a set of properties). Face-to-face interactions give lenders the best opportunity to assess that trustworthiness.

It is clear that a technology’s being able to mediate a relationship does not mean it will do so. Nineteen of the 20 businesses owners we spoke to appeared likely to stick with face-to- face modes for credit account maintenance, at least for the time being. Perhaps, if norms evolve over time and they can observe early adopters (including perhaps the one enthusiast in our sample), they may change their assessments and elect to use an m-banking/m-payments application as part of their informal credit relationships. But for now, like the Manila focus-group respondents who distinguish between ‘gifts’ and ‘loans,’ these micro-enterprise owners will put mediated interactions concerning money matters in a different category from other SMS and mobile-based activities. This tale is small and preliminary but cautionary nevertheless.

Linking adoption, impact, and use

The previous section outlined the results of a small exploratory study of one element of m-banking; we used the findings to illustrate the utility of viewing m-banking use through the lens of some cross-cutting themes from the broader research literature on information technologies in society. There is also an additional rationale; the final section of this article will argue that closer examinations of use (perhaps via these themes) can inform and strengthen future studies of m-banking/m-payments adoption or impact, making them more likely to inform policy or to lead to the development of better products and services.

Studies from the adoption perspective are sometimes criticized for requiring theoretical models that reduce use/non-use to a binary condition. Nevertheless, complementary research on use can help refine both the independent and dependent variables in such models. Pedersen and Ling (2003) made a similar point, arguing that concepts or findings from domestication, uses and gratifications, and diffusion models can all be applied to inform traditional adoption models for advanced mobile services. A better understanding of the daily practice, norms, and use patterns of m-banking/m-payments will allow the construction of a better, more valid, dependent variable: is use simply registering for the system? Engaging with it once every two weeks? Everyday? More advanced models could distinguish between people who simply utilize an m-banking/m-payments system for occasional transfers and those people who begin to actually treat their mobile as a wallet, storing value for everyday needs, or as a method for long-term savings.

In terms of independent variables for an adoption model, Luarna and Lin’s (2005) expansion of the technology acceptance model to include a trust variable illustrated how close observation of ‘use’ may improve models predicting adoption. Certainly, standard adoption models will come into play (some attributes will make the system easier to use, some people will be more likely to experiment with the systems than others, some configurations of features will offer greater relative advantage than others, and so on), but the application of an ‘ensemble lens’ or ‘use heuristic’ may identify social and social network factors which belong in the adoption equation (Valente, 1995). Almost certainly, the application of such lenses could help explicate and disaggregate trust into sub concepts that can be measured and used as predictive factors (e.g., trust in system, trust in institutions, trust in self, and trust in sender/receiver). Policy-makers and the development community have expressed enthusiasm about m-banking/ m-payments systems, presumably because they expect that widespread use of such systems would be a desirable outcome for the unbanked in the developing world. Indeed, some forms of impact are already evident: to transfer funds at a distance, particularly small amounts of money, m-banking/m-payments methods are generally less expensive than many of the alternatives available to poor households. Even if behaviors do not change and m-banking users send the same amount of money to the same people with the same frequency, the fact that households would retain a higher proportion of the money by paying lower fees is a positive impact.

Beyond cost-savings, however, the choice of the word unbanked is evidence of an assumption underpinning much of the policy-makers’ and development communities’ interest in the technology. The assumption is that households that currently do not have access to financial services will benefit from having a way to access them. In such cases, further use studies, of the kinds outlined in the previous section, could identify what the further ‘impacts’ of having a mobile-enabled bank account might be. Active use of m- banking/ m-payments services may lead to indirect impacts, such as increased family savings rates, increased incomes, and resilience to financial shocks. It could change the family dynamics concerning saving and sharing (von Reijswoud, 2007). It could lead to people staying away longer to make more money to send home in the form of remittance. The systems might reduce loss of money to petty theft and could increase people’s sense of security in their communities. At a broader level, it could bring more money into the formal banking system, improve taxation, and encourage reinvestment of money that is currently not in effective circulation (infoDEV, 2006). The list of such possible impacts is quite lengthy. Sein and Harindranath (2004), p. 19) suggested a hierarchy of impacts of the ICTs: first order effects are simply counts of the actual number of ICTs in a population (penetration rates); second-order effects are direct increases in the phenomena associated with the technologies (more mobile phones lead to more phone calls, more m-banking leads to more banking); tertiary effects are systemic or social and are not very easily observed without careful analysis. An application of the use or ensemble perspective might uncover these tertiary impacts in a way that will strengthen our understanding of the role of m-banking/m-payments services in the developing world.

CONCLUSION

The emergence of m-banking/m-payments systems has implications for the more general set of discussions about mobile telephony in the developing world. For example, it underscores the way the device blurs the domestic and the productive spheres, the social and the transactional. Each transaction is influenced by (and reinforces) the structural position of people in broader informational networks (Castells, 1996). The latest case of m-banking/ m-payments systems is a reminder that an understanding of the role of the mobile in developing societies must include its role in mediating both social and economic transactions, sometimes simultaneously. Existing theory about the significance of mobile communications in the developing world has focused on voice and text messaging (Donner, 2008). This focus is appropriate, but the emergence of mobile banking also underscores how, occasionally, innovations emerge from unexpected places and have the capability of reconfiguring the significance of a technology to its users. Mobile theory must keep pace, accounting for m-banking/m-payments systems along with other capabilities enabled by this increasingly flexible technology.

REFERENCES

Anyasi, F.I. and A.K. Yesufu, 2007. Indoor propagation modeling in brick,

zinc and wood buildings in????

Anyasi,F.I., P.A. OTUBU and F.E. ISERAMEIYA, 2008. The Merging of Telecommunication And Information

Arumugam, S., T. Jebarajam and Joy Winnie Wise, 2008.

Congestion Control Algorithm In Computer

Barnhart, C.L. and R.K. Barnhart, 2000. The World Book

Dictionary. Sixth Edition. ISBN: 0-19-431538-x

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en:wikipedia.org/wiki/mobilebanking- 7/16/2008

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/smsbanking-7/16/2008

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wilipedia.org/wiki/online,banking-7/16/2008

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/telephonebanking-7/16/2008

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/automated-teller-machine7/16/2008

www.telenor.com; visited on 10th February, 2012; Link: http://telenor.com/en/news-and-media/press-releases/2011/banking-the-unbanked-mobile-financial-services-may-improve-the-lives-of-2-bn