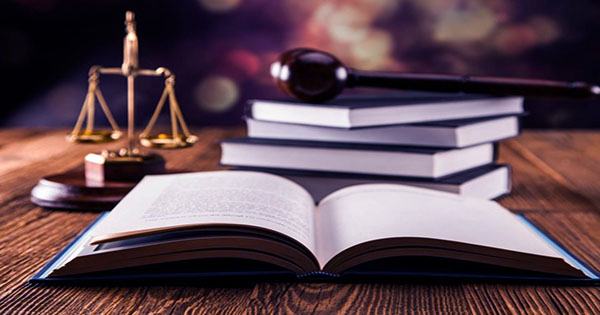

The most significant aspect in evaluating the sustainability of an idea is market timing, how relevant an idea is to the current state, and the direction of a market. A number of factors influences market timing: In the event of a pandemic, consumer tastes will skew. The cost of goods for a finite resource is increasingly scarce. The development of a unique algorithmic or genetic technique that expands the scope of what can streamline, mended, and constructed. However, the regulatory environment — meaning, government choices, the larger legal system, and its combined level of scrutiny toward a given subject — is a less-discussed region that is born not in capital markets but in the public sector.

We can deduce the achievements and problems of some important organizations today based on their interactions with the regulatory landscape and potentially use it as a lens to evaluate what areas offer unique chances for new businesses to start and scale.

In 2013, Uber co-founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick said at The Aspen Institute, “The tech comes in and evolves quicker than regulatory frameworks do, or can manage it.” The arrogant statement overlooked the fact that the regulatory landscape had influenced a number of key results for the corporation leading up to that point. After getting a cease-and-desist injunction in its initial market, California, it changed its name from UberCab to Uber. Because of the startup’s regulatory problems and iconoclastic ethos, several early workers quit. It stopped down its taxi service in New York after only a month but gained a lifeline in the city in early 2013 after being accepted through a pilot program.

Fast forward to now, and Uber has a market capitalization of around $82 billion, with Kalanick’s personal net worth estimated to be in the area of $2.8 billion. Even at its magnitude, many of the company’s most pressing growth concerns revolved around how the regulatory landscape will handle its industry. The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom recently ruled that Uber drivers might not be categorized as independent contractors.

Other sharing-economy enterprises have been influenced by the regulatory framework in a similar way. When Mayor Ed Lee authorized short-term rentals in San Francisco in October 2014, for example, Airbnb’s business model became practical. In November 2015, the city passed Proposition F, which sought to prohibit short-term rentals like Airbnb, and the company spent millions of dollars on advertising to organize voters against it.

Airbnb’s current market capitalization is $92 billion, and its CEO, Brian Chesky, is worth an estimated $11 billion. Its regulatory woes, like Uber’s, are far from over, with the company recently fined $9.6 million by the mayor of Paris. The success of these two organizations, as well as others in the sharing economy arena, demonstrates the value that the regulatory fabric can add or detract from a company’s wealth, as well as the importance of navigating the gray zones – for founding teams, early workers, investors, and customers.