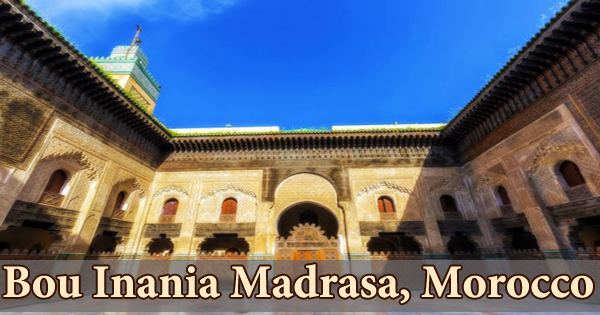

The Madrasa Bou Inania (Arabic: المدرسة البوعنانية, romanized: al-madrasa ʾabū ʿinānīya) is a madrasa in Fes, Morocco, erected in 1350–55 CE by Abu Inan Faris and highly regarded as an exceptional example of Marinid architecture and ancient Moroccan architecture around general. It is a Moroccan landmark of outstanding workmanship, located along Talaa Kebira from Bab Bou Jeloud. The name Bou Inania (Bū ‘Ināniya) comes from the name of the Marinid ruler Faris ibn Ali Abu Inan al-Mutawakkil, who founded the city (generally Abou Inan or Abu Inan for short). It was formerly known as the Madrasa al-Muttawakkiliya, but it was renamed Madrasa Bu Inania. It served as a congregational mosque and an educational college at the same time, with stores and a big public toilet along the front façade. Its interior courtyard is a marvel of intricate zellige tilework, sculpted plaster, and magnificent cedar lattice screens, beyond the enormous brass entrance doors. Students resided upstairs in smaller courts on either side that served as classrooms. Its many purposes are accommodated in a symmetrical layout that surrounds a wide courtyard with student quarters, a prayer hall, and flanking domed halls. The minaret, which stood at one end of the façade, indicated the madrasa’s role as a mosque, and its water clock set the prayer hours for all of the city’s mosques. In addition to their core duty as educational institutions, Fez’s madrasas sometimes served other purposes. The Marinid madrasas made the Maghrib, particularly Fez, a recognized intellectual center with its excellent libraries and connections to the great university of al-Qarawiyyin. Fez, one of Morocco’s most beautiful cities, is a magnificent city surrounded by natural mountains and landscapes. The medersas (Koranic universities), which give live witness to the city’s intellectual and scientific heritage, are one of the city’s most enduring symbols. The Merinid sultans created them, and they played an important role in political, educational, and cultural life. The religious elders of the Karaouine Mosque, according to history, encouraged Abu Inan Faris to establish this madrasa. The Marinids erected it as their final madrasa. The madrasa was elevated to the status of Grand Mosque, making it one of Fes’ most significant religious organizations. In the 18th century, the madrasa was restored. During Sultan Mulay Sliman’s reign, significant portions were rebuilt. The load-bearing structure, the plaster, wood, and tiled embellishments with Islamic geometric designs all received substantial repair work in the twentieth century.

Unlike many other schools of this type, the Bou Inania has a whole mosque attached to it; as a result, visitors are not permitted during prayer times. The onyx columns of the mihrab niche, which can be seen from across the prayer hall, are reminiscent of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. Abu Inan, who defied his father and declared himself sultan in 1348, did not succeed in retaining all of the new eastern provinces, but the Moroccan kingdom prospered under his reign. At the age of 31, he was murdered by his vizier on January 10, 1358. His death signaled the start of the dynasty’s demise, with future Marinid kings primarily serving as figureheads for strong viziers. The Bou Inania Medersa is known for its lavish construction, which includes sculpted stuccowork and carved cedarwood, as well as exquisite onyx and marble decorations. The lavish ornamental program of the courtyard, which is credited to the Bu ‘Inaniyya, exemplifies the distinctive Marinid translation of Nasrid palace materials and methods into a religious setting. Every surface of the courtyard façade is embellished with glazed tile dadoes, carved wood, and beautifully sculpted stucco panels. The marble-paved courtyard is separated from the arcaded hallways leading to the student apartments by wooden mashrabiyya screens. Although there is a superficial resemblance to the Nasrid palace of the Alhambra, the extraordinary delicacy and richness of the ornamental treatment, as well as its placement in a religious institution, are typical of Marinid architecture. Madrasas were important to the Marinids in maintaining their dynasty’s political legitimacy. They utilized this patronage to bolster the loyalty of Fes’ powerful but fiercely autonomous religious elites, as well as to present themselves as defenders and advocates of traditional Sunni Islam to the broader public. The madrasas also served to educate the academics and elites who ran the bureaucracies of their respective states. The madrasa is one of the few religious sites in Morocco that non-Islamic people can visit. The Dar al-Magana, a wall with a hydraulic clock erected in connection with the Madrasa Bou Inania, is located just across from it. The madrasa’s founding inscription, which can be seen inside the prayer hall, states that construction began on December 28, 1350 CE (28 Ramadan 751 AH) and ended in 1355 (756 AH). The juxtaposition between lavish decoration in the courtyard and sparse quarters for students at the Bu ‘Inaniyya and other Marinid madrasas may represent the structures’ various purposes. The main structure is shaped like an irregular rectangle with dimensions of 34.65 by 38.95 meters. It is situated between Tala’a Kebira and Tala’a Seghira, two of Fes el-most Bali’s significant avenues, and is oriented to the southeast with what was once considered the qibla (direction of prayer). The study spaces, the mosque or prayer hall area, student housing quarters, and an ablutions room are all part of the main building. The madrasas were frequently used as mosques for their respective areas as well as venues for important occasions. The madrasas became major centers of communal life when they added charitable activities like guesthouses and waqfs (endowed assets that funded the madrasa’s care) to their primary duty as religious schools. The courtyard, being the most public of the madrasa’s areas, was, therefore, the center of the decoration that would showcase the madrasa’s founder’s generous image.