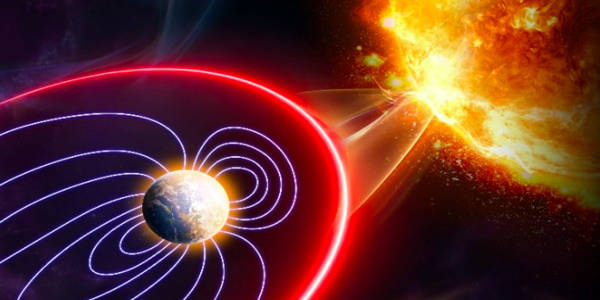

Although patterns in the timing of moderate space weather events are known, the timing of the most extreme and dangerous events was thought to be random. For the first time, this study discovered that extreme space weather occurs most frequently at predictable times during solar cycles, implying that space missions could be timed to avoid them.

According to scientists conducting the most in-depth look at solar storm timing ever, planned missions to return humans to the Moon must move quickly to avoid hitting one of the busiest periods for extreme space weather.

Researchers at the University of Reading examined 150 years of space weather data to look for patterns in the timing of the most extreme events, which can be extremely dangerous to astronauts and satellites and even disrupt power grids if they reach Earth.

For the first time, the researchers discovered that extreme space weather events are more likely to occur early in even-numbered solar cycles and late in odd-numbered cycles, such as the one that is just beginning. They are also more likely during periods of high solar activity and larger cycles, mirroring the pattern for moderate space weather.

This study found for the first time that extreme space weather occurs most frequently at predictable times during solar cycles, meaning space missions could be timed to avoid them.

The findings could have ramifications for NASA’s Artemis mission, which is scheduled to return humans to the moon in 2024 but may be pushed back to the late 2020s. Professor Mathew Owens of the University of Reading, a space physicist, stated: “Until now, the most extreme space-weather events were thought to occur at random, making it difficult to plan around them.

“However, according to this research, they are more predictable, generally following the same ‘seasons’ of activity as smaller space-weather events. They do, however, show some significant differences during the most active season, which may help us avoid harmful space-weather effects.

“These new findings should help us make better space weather forecasts for the solar cycle, which is just getting started and will last for the next decade or so. It implies that any significant space missions in the coming years, such as returning astronauts to the Moon and, later, Mars, will be less likely to encounter extreme space-weather events during the first half of the solar cycle than during the second.”

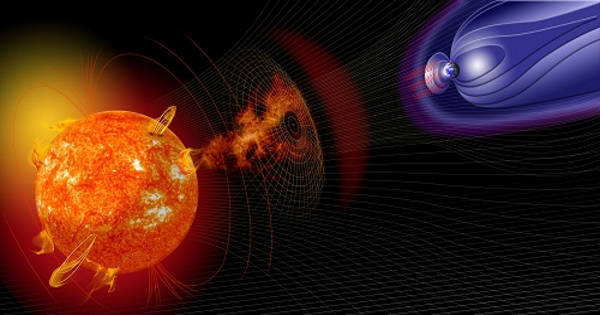

Extreme space weather is caused by massive coronal mass ejections from the Sun, which arrive at Earth and cause a global geomagnetic disturbance.

Based on previous observations, previous research has generally focused on how large extreme space weather events can be. Predicting their timing is much more difficult because extreme events are rare, leaving little historical data to identify patterns.

For the first time, the scientists used a new method that applied statistical modeling to storm timing in the new study. They examined data from the past 150 years – the longest period of data available for this type of research – collected by ground-based instruments in the UK and Australia that measure magnetic fields in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The Sun’s magnetic field cycles every 11 years, as evidenced by the number of sunspots on its surface. During this cycle, the magnetic north and south poles of the Sun alternate. Each cycle has a solar maximum period, during which solar activity is at its peak, and a quiet solar minimum period.

Previous research has found that moderate space weather is more likely during the solar maximum than during the solar minimum, and it is more likely during cycles with a higher peak sunspot number. This is the first study to show that the same pattern holds true for extreme events.

The most important discovery, however, was that extreme space weather events are more likely to occur early in even-numbered solar cycles and late in odd-numbered cycles, such as cycle 25, which began in December 2019.

This could be due to the orientation of the Sun’s large-scale magnetic field, which flips at solar maximum to point opposite to Earth’s magnetic field early in even cycles and late in odd cycles. More research will be required to validate this theory.

This new study on space weather timing allows for the prediction of extreme space weather during solar cycle 25. As a result, it could be used to plan the timing of activities that could be impacted by extreme space weather, such as power grid maintenance on Earth, satellite operations, or major space missions.

According to the findings, any major operations planned beyond the next five years will need to account for the increased likelihood of severe space weather late in the current solar cycle, between 2026 and 2030.

A major solar eruption in August 1972, between NASA’s Apollo 16 and 17 missions, was powerful enough to cause major technical or health problems for astronauts if it had occurred while they were en route to or around the Moon.