Coral reefs are diverse marine ecosystems formed primarily by colonies of tiny animals called coral polyps. These polyps belong to the phylum Cnidaria, and they secrete a hard exoskeleton made of calcium carbonate, which forms the basis for the reef structure.

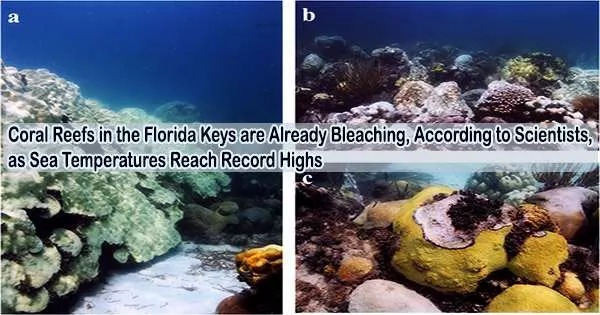

Due to record-high water temperatures this summer, some coral reefs in the Florida Keys are losing their color weeks earlier than usual, placing their health in jeopardy, federal scientists said.

The corals should be vibrant and colorful this time of year, but are swiftly going white, said Katey Lesneski, research and monitoring coordinator for Mission: Iconic Reefs, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched to protect Florida coral reefs. Over time, as new generations of coral polyps grow and build upon the remains of their ancestors, coral reefs can develop into vast and intricate formations.

“The corals are pale, it looks like the color’s draining out,” said Lesneski, who has spent several days on the reefs over the last two weeks. “And some individuals are stark white. And we still have more to come.”

This week, NOAA scientists upgraded the Keys’ alert level for their highest heat stress level out of five Alert Level 2 for coral bleaching. That level is reached when the average water surface temperature is about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) above the normal maximum for eight straight weeks.

Surface temperatures around the Keys have been averaging about 91 degrees (33 Celsius), well above the normal mid-July average of 85 degrees (29.5 Celsius), said Jacqueline De La Cour, operations manager for NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program. Previous Alert Level 2s were reached in August, she said.

Coral reefs are made up of tiny organisms that link together. The algae that inhabits the reefs and feeds the corals is what gives them their color. The coral expels the algae when temperatures rise too high, leaving the reefs looking bleached or white. The corals can hunger and are more prone to illness, but it doesn’t necessarily imply they are dead.

The corals are pale, it looks like the color’s draining out. And some individuals are stark white. And we still have more to come.

Katey Lesneski

Andrew Bruckner, research coordinator at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, said some coral reefs began showing the first signs of bleaching two weeks ago. Then in the last few days, some reefs lost all their color. That had never been recorded before Aug. 1. The peak for bleaching typically happens in late August or September.

“We are at least a month ahead of time, if not two months,” Bruckner said. “We’re not yet at the point where we are seeing any mortality … from bleaching. It is still a minor number that are completely white, certain species, but it is much sooner than we expected.”

De La Cour and Bruckner acknowledged that making predictions for the remainder of the summer is challenging. A tropical storm or hurricane may churn the water and bring it down while the temperatures could continue to rise and be disastrous. Temperatures may drop if dusty air from the Sahara Desert drifts over the Atlantic and settles over Florida.

Over the past 50 years, the Keys waters have lost 80% to 90% of their coral due to climate change and other causes, according to Bruckner. Coral reefs act as a natural barrier against storm surge from hurricanes and other storms, which has an impact on not just the marine life that depends on the reefs for survival but also humans.

Additionally, there is a financial impact because coral reefs are crucial for fishing, scuba diving, and snorkeling tourism.

“People get in the water, let’s fish, let’s dive that’s why protecting Florida’s coral reef is so critical,” De La Cour said.

Both scientists said it is not “all doom and gloom.” A 20-year, large-scale effort is underway to rebuild Florida’s coral back to about 90% of where it was 50 years ago. Bruckner said “scientists are breeding corals that can better withstand the heat and are using simple things like shade covers and underwater fans to cool the water to help them survive.”

“We are looking for answers and we are trying to do something, rather than just looking away,” Bruckner said.

“Breeding corals can encourage heat resistance in future generations of the animals,” said Jason Spadaro, coral reef restoration program manager for Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Sarasota, Florida. That could be vital to saving them, he said.

The coral bleaching is worse in the lower Keys than in the more northern sections of the region, according to Spadaro and others who have visited the corals. The Keys have experienced bad bleaching years in the past, but this year it is “really aggressive and it’s really persistent,” he said.

“It’s going to be a rough year for the reef. It hammers home the need to continue this important work,” he said.

The early bleaching is happening during a year when water temperatures are spiking earlier than normal, said Ross Cunning, a research biologist at Shedd Aquarium in Chicago. The Keys are experiencing water temperatures above 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius), which would normally not occur until August or September, he said.

The hot water could lead to a “disastrous bleaching event” if it does not wane, Cunning said.

“We’re seeing temperatures now that are even higher than what we normally see at peak, which is what makes this particularly scary,” Cunning said.

De La Cour said she has no doubt that human-made global warming causes the warming waters and that needs to be fixed for coral to survive.

“If we do not reduce the greenhouse gas emissions we are emitting and don’t reduce the greenhouse gases that are already in the atmosphere, we are creating a world where coral reefs cannot exist, no matter what we do,” she said.