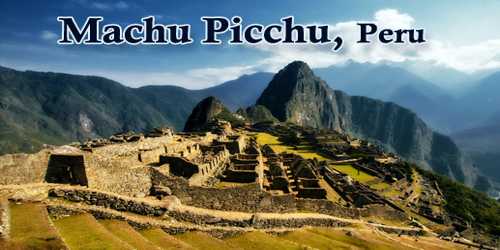

“Machu Picchu” (English: /ˈmɑːtʃuː ˈpiːktʃuː/ or /ˈpiːtʃuː/, Spanish: ˈmatʃu ˈpi(k)tʃu; Quechua: Machu Pikchu [ˈmatʃʊ ˈpɪktʃʊ]), also spelled ‘Machupijchu’, site of ancient Inca ruins located about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of Cuzco, Peru, in the Eastern Cordillera de Vilcabamba of the Andes Mountains. The site is famous for its sophisticated dry-stone walls that fuse huge blocks without the use of mortar, intriguing buildings that play on astronomical alignments and panoramic views.

It is perched above the Urubamba River valley in a narrow saddle between two sharp peaks Machu Picchu (“Old Peak”) and Huayna Picchu (“New Peak”) at an elevation of 7,710 feet (2,350 meters). One of the few major pre-Columbian ruins found nearly intact, Machu Picchu was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983. In 2007, Machu Picchu was voted one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in a worldwide Internet poll.

Machu Picchu’s weather generally warm and humid during the day and cool during the night. Temperatures range between 52 and 81 degrees Fahrenheit (11 and 27 degrees Celsius). This zone is normally rainy (1955 mm), especially between November and March. Structures at Machu Picchu were built with a technique called &ldquo ashlar.” Stones are cut to fit together without mortar. Remarkably, not even a piece of paper can fit in between two stones. The citadel has two parts: Hanan and Urin according with the Inca tradition. The best ways to visit it are to ride the train from Cusco to the switchback road or to take an amazing multi-day hike along the Inca Trail.

Often mistakenly referred to as the “Lost City of the Incas”, ‘Machu Picchu’ is the most familiar icon of Inca civilization. The Incas built the estate around 1450 but abandoned it a century later at the time of the Spanish conquest. Although known locally, it was not known to the Spanish during the colonial period and remained unknown to the outside world until American historian Hiram Bingham brought it to international attention in 1911. It (Machu Picchu) was built in the classical Inca style, with polished dry-stone walls. Its three primary structures are the Intihuatana, the Temple of the Sun, and the Room of the Three Windows. Most of the outlying buildings have been reconstructed in order to give tourists a better idea of how they originally appeared. By 1976, 30% of Machu Picchu had been restored and restoration continues.

In the Quechua native language, “Machu Picchu” means “Old Peak” or “Old Mountain.” Many of the stones that were used to build the city weighed more than 50 tons. It was built starting 1450-1460. Construction appears to date from two great Inca rulers, Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui (1438-1471) and Túpac Inca Yupanqui (1472-1493). There is a consensus among archaeologists that Pachacutec ordered the construction of the royal estate for himself, most likely after a successful military campaign. Though Machu Picchu is considered to be a “royal” estate, surprisingly, it would not have been passed down in the line of succession. Rather it was used for 80 years before being abandoned, seemingly because of the Spanish Conquests in other parts of the Inca Empire. It is possible that most of its inhabitants died from smallpox introduced by travelers before the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the area.

In 1911, Hiram Bingham was a history professor intent on finding the last place where the Incas of Vilcabamba were. Guided by a young boy from Mandorpampa, Bingham arrived at the ruins and thought this is the place where the Incas were established after losing their territory. It wasn’t until after his death in the 1950s that the real Vilcabamba was discovered further west of Machu Picchu citadel.

Little information describes human sacrifices at Machu Picchu, though many sacrifices were never given a proper burial, and their skeletal remains succumbed to the elements. However, there is evidence that retainers were sacrificed to accompany a deceased noble in the afterlife. Animal, liquid and dirt sacrifices to the gods were more common, made at the Altar of the Condor. The tradition is upheld by members of the New Age Andean religion.

Few of Machu Picchu’s white granite structures have stonework as highly refined as that found in Cuzco, but several are worthy of note. In the southern part of the ruin is the Sacred Rock, also known as the Temple of the Sun (it was called the Mausoleum by Bingham). It centers on an inclined rock mass with a small grotto; walls of cut stone fill in some of its irregular features. Rising above the rock is the horseshoe-shaped enclosure known as the Military Tower. In the western part of Machu Picchu is the temple district, also known as the Acropolis. The Temple of the Three Windows is a hall 35 feet (10.6 meters) long and 14 feet (4.2 meters) wide with three trapezoidal windows (the largest known in Inca architecture) on one wall, which is built of polygonal stones. It stands near the southwestern corner of the Main Plaza. Also near the Main Plaza is the Intihuatana (Hitching Post of the Sun), a uniquely preserved ceremonial sundial consisting of a wide pillar and pedestal that were carved as a single unit and stand 6 feet (1.8 meters) tall.

In 2012, one year after the 100th anniversary of Machu Picchu’s scientific discovery, all the artifacts excavated by Bingham team’s and shipped to Yale University’s Peabody Museum, were finally returned to Peru. These artifacts are currently on display at Casa Concha (Machu Picchu Museum) in Cusco.

Information Sources: