Tetanus (Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention)

Definition: Tetanus is a serious bacterial (Clostridium tetani) disease that affects our nervous system, leading to painful muscle contractions, particularly of our jaw and neck muscles. It is commonly known as “lockjaw.”

The word tetanus comes from the Ancient Greek: τέτανος, translit. tetanos, lit. ‘taut’, which is further from the Ancient Greek: τείνειν, translit. teinein, lit. ‘to stretch’.

Tetanus is a serious bacterial infection. The bacteria exist in soil, manure, and other environmental agents. A person who experiences a puncture wound with a contaminated object can develop the infection, which can affect the whole body. It can be fatal.

Fractures of the spine or other bones may occur as a result of muscle spasms and convulsions. Abnormal heartbeats and coma can occur, as can development of pneumonia and other infections. Death is particularly likely in the very young and in old people.

People of all ages can get tetanus. But the disease is particularly common and serious in newborn babies. This is called neonatal tetanus. Most infants who get the disease die. Neonatal tetanus is particularly common in rural areas where most deliveries are at home without adequate sterile procedures.

Tetanus often begins with mild spasms in the jaw muscles – also known as lockjaw or trismus. The spasms can also affect the facial muscles resulting in an appearance called risus sardonicus. Chest, neck, back, abdominal muscles and buttocks may be affected. Back muscle spasms often cause arching, called opisthotonos. Sometimes the spasms affect muscles that help with breathing, which can lead to breathing problems

Tetanus is a medical emergency. It will need aggressive wound treatment and antibiotics. Treatment focuses on managing complications until the effects of the tetanus toxin resolve.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Tetanus: Tetanus at any age is a medical emergency best managed in a referral hospital. While there isn’t a specific laboratory test to diagnose tetanus, there are tests that can help exclude diseases with symptoms similar to tetanus, such as meningitis, rabies, and strychnine poisoning.

The “spatula test” is a clinical test for tetanus that involves touching the posterior pharyngeal wall with a soft-tipped instrument and observing the effect. A positive test result is the involuntary contraction of the jaw (biting down on the “spatula”) and a negative test result would normally be a gag reflex attempting to expel the foreign object. A short report in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene states that, in a patient research study, the spatula test had a high specificity (zero false-positive test results) and a high sensitivity (94% of infected patients produced a positive test).

Though there’s no cure for tetanus, treatment is critical to preventing complications. Any cut or wound must be thoroughly cleaned to prevent infection. A tetanus-prone wound should be treated by a medical professional immediately.

Treatment involves caring for the wound and taking medications to ease symptoms. Treatment may include the following:

- Surgery to clean the wound and remove the source of the poison

- Antibiotics are given orally or with an injection

- Medicine (tetanus immune globulin) to reverse the poison that hasn’t yet bonded to nerve tissue

- Muscle relaxers, such as diazepam (Valium)

- Strong sedatives to control muscle spasms

- Other medications, such as magnesium sulfate, beta-blockers or morphine may help regulate involuntary muscle activity, such as a patient’s heartbeat and breathing

- Breathing support with oxygen, a breathing tube, and a breathing machine

- Bed rest with a calm environment (dim light, reduced noise, and stable temperature)

In addition to treatment, feeding through nasoduodenal tubes, gastrostomy tube feedings, or parenteral hyperalimentation (nutrients provided through a catheter) may be required to avoid choking and to maintain healthy nutrition throughout recovery.

Doctors may prescribe penicillin or metronidazole for tetanus treatment. These antibiotics prevent the bacterium from multiplying and producing the neurotoxin that causes muscle spasms and stiffness. Patients who are allergic to penicillin or metronidazole may be given tetracycline instead.

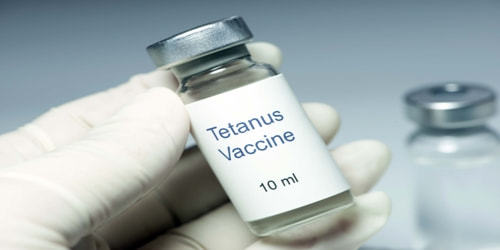

Vaccination: The tetanus vaccine is routinely given to children as part of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis (DTaP) shot.

The DTaP vaccine consists of five shots, usually given in the arm or thigh of children when they are aged:

- 2 months

- 4 months

- 6 months

- 15 to 18 months

- 4 to 6 years

A booster is normally given between the ages of 11 and 18 years, and then another booster every 10 years. If an individual is traveling to an area where tetanus is common, they should check with a doctor regarding vaccinations.

Preventions of Tetanus: Tetanus can be prevented by vaccination with tetanus toxoid. The CDC recommends that adults receive a booster vaccine every ten years, and standard care practice in many places is to give the booster to any patient with a puncture wound who is uncertain of when he or she was last vaccinated, or if he or she has had fewer than three-lifetime doses of the vaccine. The booster may not prevent a potentially fatal case of tetanus from the current wound, however, as it can take up to two weeks for tetanus antibodies to form.

Immunizing infants and children with DTP or DT and adults with Td prevents tetanus. More recently, some countries have been using a combination vaccine that includes vaccines for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, vitamin A (HepB), and sometimes Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib).

Neonatal tetanus can be prevented by immunizing women of childbearing age with tetanus toxoid, either during pregnancy or outside of pregnancy. This protects the mother and enables tetanus antibodies to be transferred to her baby.

Clean practices are especially important when a mother is delivering a child, even if she has been immunized. People who recover from tetanus do not have natural immunity and can be infected again and therefore need to be immunized.

Tetanus toxoid can be given in case of a suspected exposure to tetanus. In such cases, it can be given with or without tetanus immunoglobulin (also called tetanus antibodies or tetanus antitoxin). It can be given as intravenous therapy or by intramuscular injection.

Information Source: