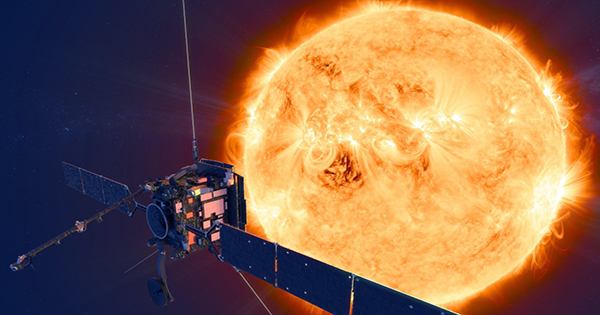

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will soon become a fabricated object to reach the Sun. To get there, it assisted by Venus and some creative orbit design. In July 2020, during a flyby to use the planet’s gravity to bend the Sun’s orbit, it scattered several images of the planet. These photos show something unexpected: the surface of Venus. Why is it unexpected? Unlike Earth, Venus covered in a thick blanket of dry clouds. To see them, previous spacecraft, including Akatsuki in Japan, used radar and infrared cameras. The Parker Solar Probe is not equipped with any. Its Wide-Field Imager (WISPR) designed to create visible images of the Sun’s inner heliosphere in the visible light of the solar corona.

“WISPR is suitable and tested for visible-light observations. We expected to see the clouds, but the camera just sank, “said Angels Vourlidas, a scientist with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory’s WIPR project, in a statement. Brian Wood, an astrophysicist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., and a member of the WISPR team, said, “The WISPR effectively captured the heat dissipation on the surface of Venice.”

These observations of Venus could have a huge impact on the mission. If WISPR can see more than visible light, it will provide more insight into the sun’s internal workings. Astronomers studying Venus have also received more than expected from the Parker Solar Probe that they are excited with this observation. The images show the planet’s night light and the vast Aphrodite Terra, the largest elevation on the planet.

“We’re really looking forward to these new images,” said Javier Peralta, a planetary scientist from Akatsuki’s team who collaborated with Akatsuki on the Parker Solar Probe, which has been orbiting Venus since 2015. The surface of Venus and the nightglow – possibly from oxygen – in the planetary organs, could make a valuable contribution to the study of the Venetian surface.” The closest last pass to Venus by probe was last week, February 20, so some more exciting science should come soon.