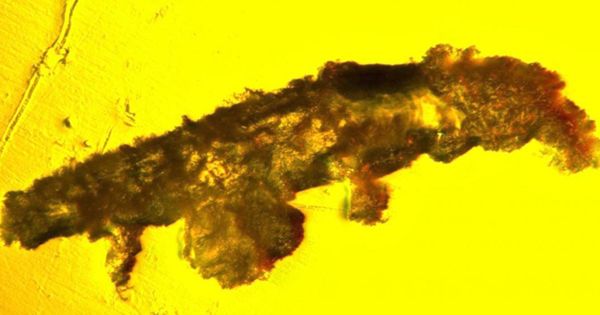

A new tardigrade species has been discovered petrified in Dominican amber that dates back 16 million years. It is not only the fourth tardigrade fossil to discovered and named, but it is also the first from the Cenozoic, the current geological epoch. According to the study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the notoriously tenacious beastie measures just over half a millimeter (0.02 inches) and belongs to the Isohypsibioidea superfamily.

According to the researchers, Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus is also the best-imaged tardigrade fossil to date, with characteristics of the creature’s mouthparts and tiny tiny claws unequaled in the fossil record. In a statement, Phil Barden, co-author of the study and assistant professor of biology at New Jersey Institute of Technology, said, “The discovery of a fossil tardigrade is definitely a once-in-a-generation occurrence.”

“What makes tardigrades so unique is that they are an ancient lineage that has seen it all on Earth, from the extinction of the dinosaurs to the rise of plant colonization on land.” Despite this, they considered a “ghost lineage” by paleontologists due to the lack of a fossil record. Finding any tardigrade fossil remains is a thrilling event since it allows us to observe their evolution over time.”

“With our new study, the total number of specimens is down to only four, of which only three have been fully characterized and named, including Paradoryphoribius.” “Professor Javier Ortega-Hernández, a senior author, gave his two cents.”This publication covers around a third of the tardigrade fossil record that has discovered to date. Furthermore, Paradoryphoribius is the sole tardigrade with a buccal apparatus in the fossil record.”

Despite their legendary toughness (tardigrades can survive being shot out of a rifle and have survived all five known mass extinction events), fossilized tardigrades are extremely rare. As a result, “little about their evolutionary history is known.”

This is possibly due to their size, due to its minuscule size, Pdo. chronocaribbeus “wasn’t spotted for months,” according to Barden, who describes it as “a pale speck in amber.” Thankfully, the tiny creature was located and observed using confocal microscopy, a technology that visualizes organisms using lasers rather than light. Because of the additional detail and view of internal morphology that this provided, what first appeared to be a modern tardigrade could confirm as a new species?

“[F]or the first time, we’ve examined the interior anatomy of the foregut in tardigrade fossil and discovered combinations of features that we don’t find in live organisms.” “Not only does this allow us to assign this tardigrade to a new genus, but it also allows us to investigate the evolutionary changes that this group of organisms has undergone over millions of years,” said Marc A. Mapalo, the study’s lead author and a graduate student at Harvard’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

The researchers were able to put a minimum age on the Isohypsibioidea family simply by dating the amber. The study also argues that the rarity of tardigrade fossil records may explained by the tardigrades’ preference for amber preservation, which could be an undiscovered resource for tardigrade fossils. The researchers hope that their findings will push others to examine amber samples more closely in the quest to understand more about these fascinating invertebrates.

“When it comes to understanding living tardigrade communities, we’re only scratching the surface,” Barden said, “particularly in locations like the Caribbean where they haven’t been surveyed.” “This work serves as a reminder that, for all the tardigrade fossils we have, we also know very little about the live species on our planet today.”