Nemo: Shipping Industry Shaken up by these Cargo Drones

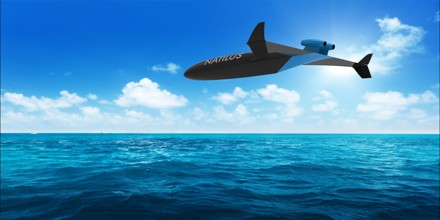

Drone technology is developing at a rapid pace, and being used for all kinds of things. The next big thing could come from a tiny start-up in California’s Bay Area: creating drones large enough to carry freight across the Pacific Ocean. Natilus is launching its first drone, by the second quarter, and Mobility Buzz has obtained the first look at the prototype.

Commercial passenger jets fly at an altitude of around 30,000 feet or higher. Imagine sitting in a window seat of one of those giant aluminum tubes a few years from now as it makes its way across the Pacific Ocean.

Shipping by air is fast, but expensive. Boat is much cheaper, but very slow. So why not send all those boxes and packages on an un-piloted, amphibious Boeing 777-sized drone that can fly point to point and eventually drop off as much as 200,000 pounds of cargo at a seaside port? It would carry that cargo at about half the cost of normal air freight thanks to a more efficient use of fuel and the lack of an expensive crew.

About “Nemo”

Made of carbon fiber composites and powered by jet engines, the drones would take off from the water, eliminating the need for landing gear and long landing strips. It would land on water several miles from port before taxiing to the dock, where cranes would unload the cargo.

The amphibious drones would cruise at an altitude of about 20,000 feet and would fly slower than piloted cargo planes.

Shipping 200,000 pounds of freight from Los Angles to Shanghai via drone, for example, would take about 30 hours at a cost of about $130,000, the company says. Delivery of the same cargo by a Boeing 747 takes about 11 hours and costs about $260,000. Moving the same cargo to Shanghai by ship would cost about $61,000 but would take three weeks.

Natilus

Natilus Inc., of Richmond, Calif., is building a 30-foot prototype drone that could take to the air for the first time later this year. If all goes as planned, the firm will develop an 80-foot drone that will begin flying routes from Los Angeles to Hawaii in 2019. A 140-foot drone with a 200,000-pound cargo capacity could be flying routes to China starting in 2020.

Natilus aims to build a large-scale commercial drone the size of a Boeing 777 to help reduce the cost of air freight by 50%, Matyushev said (Natilus’ co-founder and chief executive). The company focuses on shipping goods, such as perishables, pharmaceuticals, and high-tech products. Natilus hopes to build hundreds of the drones, some of which will be sold directly to customers—ideally to companies like UPS and FedEx as well as “medium freight forwarders” like Whole Foods and Costco.

The prototype, called “Nemo,” is about the size of a small predator military drone, Matyushev said.

Matyushev notes that Natilus may operate some of the drones itself as a freight airline but fly them under the brand logos of customers. When asked to comment on Natilus’s plans or the future of drone delivery in general, a UPS spokesperson declined to comment, “Other than to say that we see promising potential applications in a number of areas.” The company adds that it has already been testing drones for a variety of applications, ranging from humanitarian aid to commercial delivery and inventory inspection.

Natilus, which has raised $750,000 from venture capitalist Tim Draper and was incubated at the aviation-oriented Starburst Accelerator in Los Angeles, will power its drones with turboprop and turbofan engines and standard jet fuel, sending them on missions at an altitude of approximately 20,000 feet. That’s well below commercial planes, but high enough to be fuel-efficient. Matyushev says trips across oceans would cost about half of what current commercial air freight transport runs, traveling a bit slower than manned cargo aircraft.

Dr. John Michael Robbins, an assistant professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida, called cargo drones “extremely feasible” in an email to NBC News MACH, adding “it will take some time” for them to be proven safe and efficient. “The aircraft not only have to be built and tested in order to pass the rigorous process of certification, but society has to accept the technology in order for it to truly become commercially viable.”

One of Natilus’s goals is to use lower shipping costs to reduce the price of goods to consumers. “That’s the grand vision,” Matyushev says.

For now, Natilus is focused on getting its 30-foot prototype, which is about 70% complete, ready for summer tests in San Pablo Bay, just northeast of San Francisco. If those go well, then it’s full steam ahead on the 777-sized model, provided that additional funding and the engineering talent needed to build it materialize.